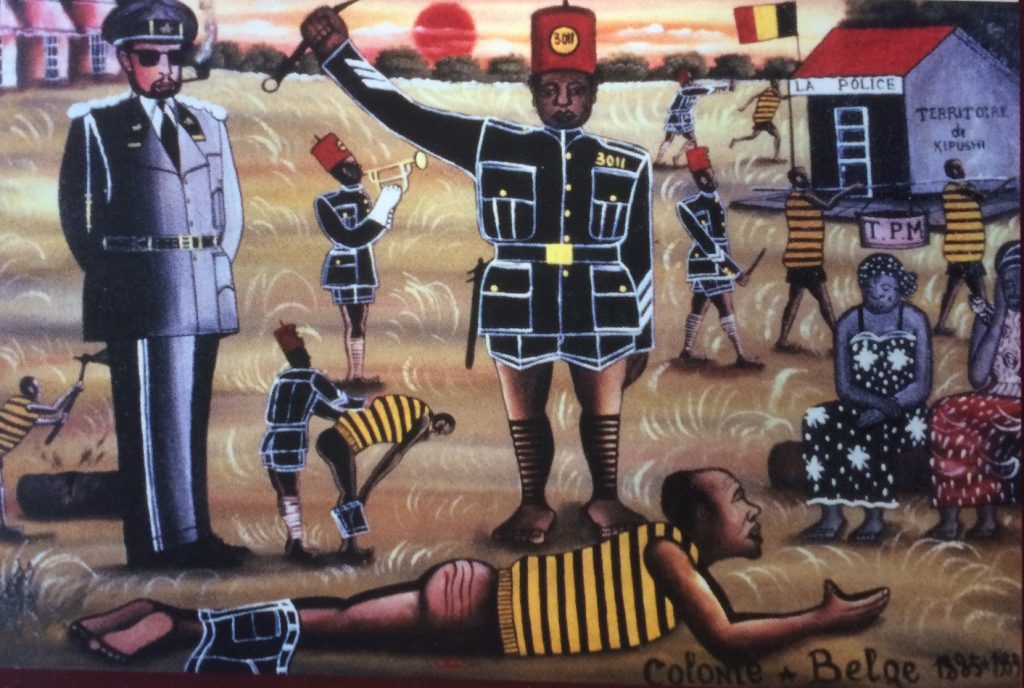

This course is an introduction of the history of Africa through the lens of the transatlantic slave trade from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. This traffic was one of the main crossroads of the history of Africa’s long and troubled relationship with both Europe and the Americas. The course’s primary goal, however, lies not in investigating the slave trade but in studying the political, economic, social, and cultural histories of a number of African societies that participated in the trade. Given the large number and vast diversity of African societies, the course cannot possibly present a comprehensive survey. Instead, it zooms in from broad questions such as the connections of Africans with Europeans, the roles of Africans in this traffic, and the interrelated political and cultural landscapes to the specifics of regionally grounded histories from the emergence of the Atlantic slave trade to the beginning of European colonialism in Africa.

The course will familiarize students with various genres and formats of historical writing such as introductory books of African history, primary sources, textbooks, monographs, an annotated diary (of an African slave trader), scholarly articles, and a graphic history.

This is a course on pre-1900 African History. If you want to know about today´s Africa, look at “Africa is a Country” -it is not a country, that´s the title of the blog.