Wednesday, November 9th marked the date of the opening of the War Diaries exhibit at the Viewpoint Gallery within UCI’s Student Center.

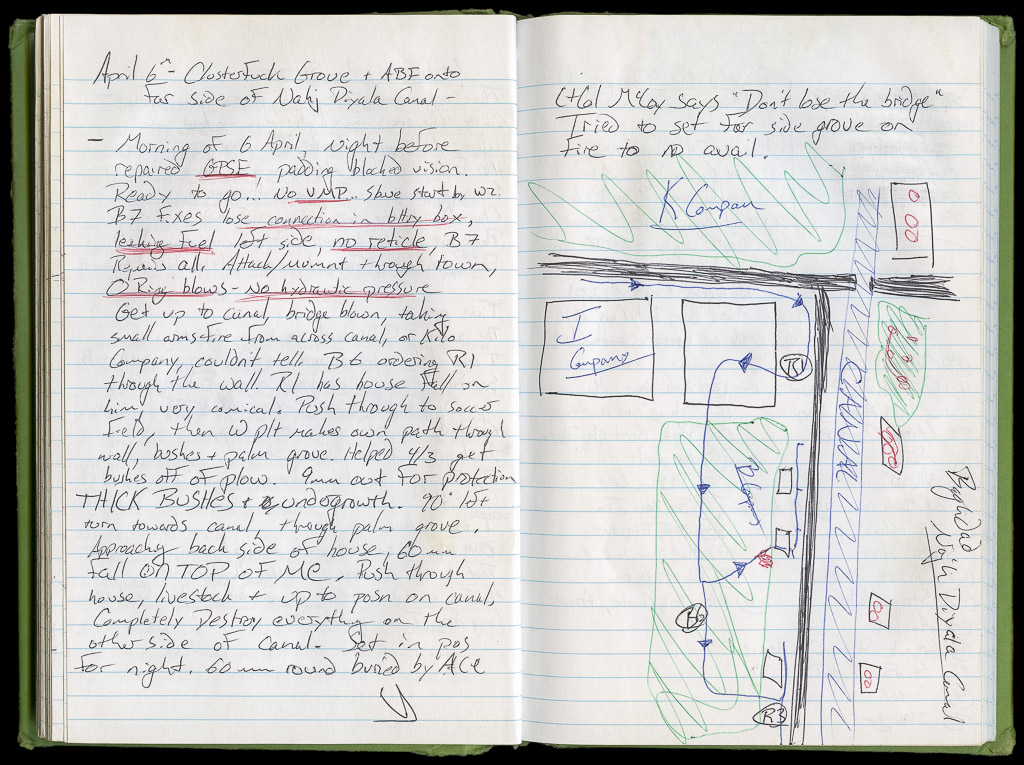

The exhibit showcased blown up portions of heart-wrenching diaries donated to the School of Humanities by Tim McLaughlin, a Marine Corps Tank Commander stationed in Iraq after the 2003 invasion. It was set up so that, while walking through the exhibit, you could read the diaries in order, allowing for the audience to feel what McLaughlin was feeling when he sat down to write the entries.

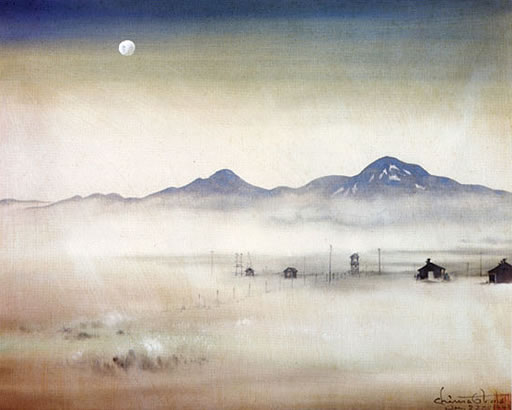

Along with the diary entries, the exhibit also showcased texts written by journalist and write Peter Maass and photos taken by photojournalist Gary Knight. By seeing this work, juxtaposed to that of the memoir-like diary entries posted high on the walls of the exhibit, I felt as though I was taken into the Iraq war itself, because not only was I getting the perspective from a Tank Commander, I was receiving an arguably more objective perspective from the texts by Knight, while the photographs set the stage up for both.

To tie it all together, the exhibit featured a video installation of actual news footage from 2003 that successfully took the audience back to when the invasion of Iraq had just begun.

This collaboration of work successfully illuminated the perspectives of people stationed in Iraq, fighting the war and documenting the horrors of it through journalism or photography. It also allowed insight of the experiences of those back home, witnessing the horrors of war through the lens of such journalists and photographers. It sustains the importance of being able to document experiences, in order to recreate similar scenarios, essentially keeping the stories told by so many people, alive.

The War Diaries Exhibit was successful in allowing us, outsiders, a glimpse into the experience of the Iraq War through the lens of Tim McLaughlin, Gary Knight, and Peter Maass.