In the Disability Justice primer Skin, Tooth, and Bone: The Basis of Movement is Our People, the Bay Area-based disability performance project Sins Invalid writes,

“We may or may not survive as a species, but can move forward in love for each other regardless of where we are going.”

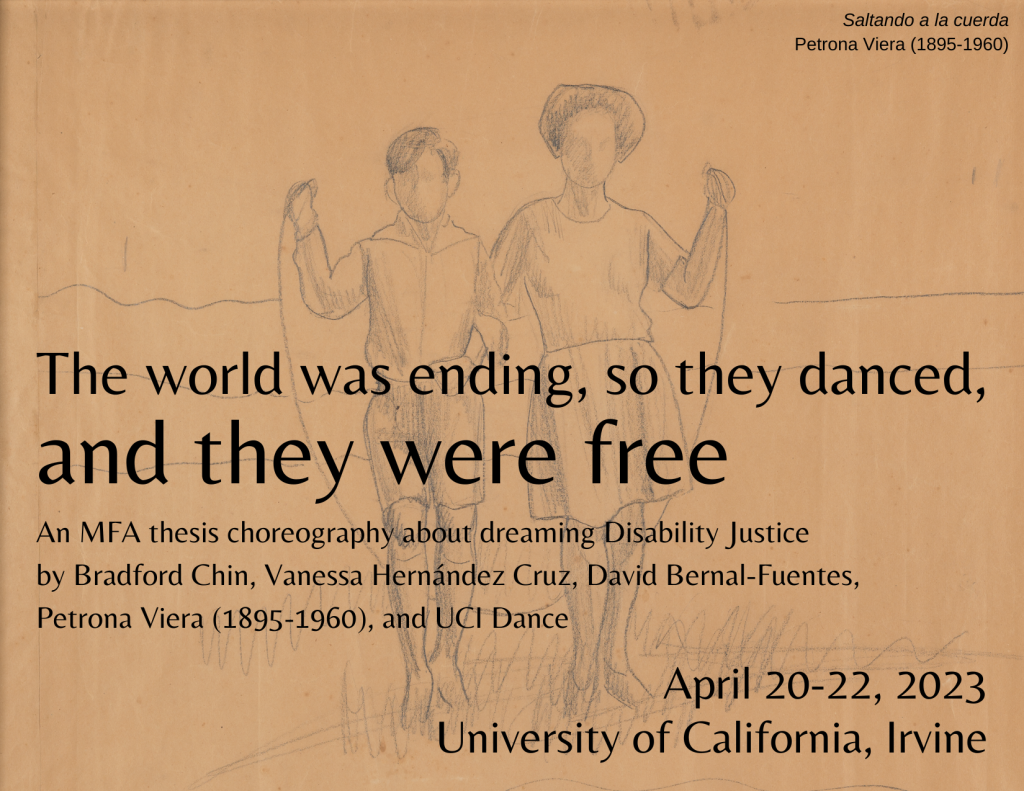

The world was ending, so they danced, and they were free (premiere) is both a lament and a dream for a more accessible and more just future. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the disconnection between the increased awareness of disability and the capitalist insistence on production over personhood. In this dissonance lies the ever-widening gap between our society and our humanity. Even with pleas from the disabled, immunocompromised, and other vulnerable communities – the communities who are most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic – our society has been loathe to pause and forge new pathways forward. Instead, our society continues to choose, as it has always done, to abandon those who are in need for the sake of capitalism: the production of goods, yes, but also the manufactured scarcity of resources and the production of profits that benefit the rich few rather than our communities.

This “advancement at all costs” mindset is also present in dance. As sociologist Lacey Wood once remarked to me, dance is simultaneously a conduit into and a gatekeeper against disability. Physical, musculoskeletal injuries are common among dancers and, even if not acutely career-ending, can stay with the dancer for the rest of their life. Many conventional teaching and choreographic practices also result in mental and emotional tolls – such as body dysmorphia, fatphobia, and eating and stress disorders – that also stay with dancers for the rest of their lives. All of this for what end?

Despite its frequent production of disability, current mainstream dance aesthetics hold little room for even the conception of disability. The Centers for Disease Control states that over 25% – one in four – US American adults are disabled (in the medicalized model of disability diagnosis). How many dancers do you know who openly identify as disabled? How many disability-centered dance companies exist in the US? I can guarantee that those numbers are not one in four, and that is an indictment of the current state of the dance world.

Whether we identify as disabled or not, and whether we choose to accept it or not, ableism impacts all of us. Disability is not a single, standalone identity, but is inseparable from other forms of identity. The construction of ableism – not just outright discrimination, but how we define what is “normal” or not – simultaneously informs and is informed by the construction of racism, sexism, classism, and other forms of oppression and power. That all of our struggles are linked is the first principle of Disability Justice.

The world was ending, so they danced, and they were free invites you to join the artistic collaborators in an insistence on potentially uncomfortable questions. Why must things be the way they are? Why must some people be left behind? What can be done differently, and what would it take to do things differently now? How can we move forward in love for each other regardless of where we are going?

We do not know where this dream for an accessible future will take us or what this accessible future looks like. All we know is that a change is desperately needed now. We hope that you join us in dreaming and shaping our future together.

Read more about the work: Thesis 2023 / Experiencing the Work

Return to home page: Thesis 2023 / Home