On October 13, professors from the University of California, Riverside, the University of California, Merced, and Occidental College in Los Angeles, joined us on campus to discuss Japanese Internment on American soil during the 1940s.

Professor Jason Weems of the Department of History at UCR introduced the way Americans viewed the Japanese American citizens after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. His lecture included depictions of Japanese cartoons used to “educate the ignorant American eye” and teach how to differentiate between the fellow Chinese and the alien-enemy “Japs.”

This set the tone for paintings also included in his lecture, such as “The Yellow Danger,” and “The Yellow Peril” which both illuminated the racism against Japanese Americans as they were depicted to have exaggerated “Japanese” features, much like the cartoons he had presented earlier. “Dragon-like” representations of the Japanese soldiers were also commonly seen in paintings, while US Military propaganda depicted them as aggressive and hostile.

Paintings like Bloody Saturday (1937), by artist H. S. Wong, in juxtaposition to the other paintings, worked in the opposite way, shedding light onto the severity of the internment of Japanese Americans, most of whom were born in the United States and had no ties to Japan at all. This, the professor pointed out, showed how the fear Americans felt insinuated the actions taken against the Japanese after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

But inside the camps, art was a force that worked differently.

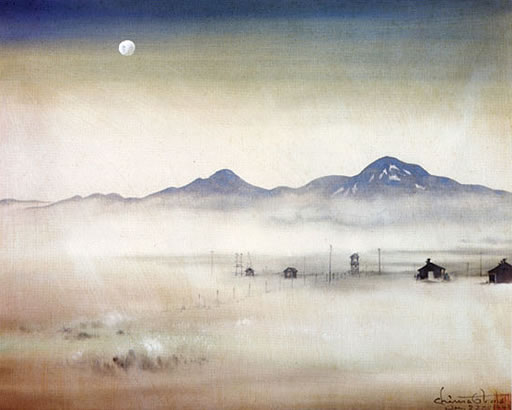

Photographs, paintings and other forms of art were not used to depict the horrors of incarceration. Rather, these forms of art were used to “make violence beautiful,” said Professor Weems. They were ways in which the Japanese normalized their experiences, so as to have normal boundaries for their families to reside in.

Moonlight Over Topaz (1942), as presented by the visiting professor from UCM, illuminated the same normalization of life within the camps. He argued, the Japanese painted in order to keep the hope for freedom alive amongst the community within the barbed wires.

It was when this professor pointed towards the use of art as a form of aestheticizing traumatic experience, that I was left in awe. I had never thought of this––but this is what the Japanese did while incarcerated unjustly; they manipulated the concept of beauty and used it as a coping mechanism in order to maintain a sense of normality and to express their imagination. This expression was their only form of keeping what power they had left while still behind the barbed wires.

A lot of what the Documenting War project does gives voice to individuals whose voices have been drowned out by larger forces––these guests and their lectures all proved successful in doing so: in giving voices to the Japanese interned within the concentration camps on American soil––a wrongdoing that, although has stained our country, is too often not spoken about.