The election of a man with no political experience that won the hearts and minds of many in America by loudly proclaiming what for years the political Right has been saying has been denied them by PC culture: the ability to say out loud that religious minorities, blacks, women, gays and transgender folk, non-white immigrants, non-white citizens, feminists, fatties, and uglies have gotten too uppity and comfortable and need to be reminded of their place; that we represent the limit to the America dream (and not the forms of economic dispossession that enable the .1% to hold onto obscene amounts of wealth and resources). There is a firm belief that the ills of society are caused by the barbarians that have infected America from within and the barbarians that remain at the gate waiting to take from us what ours. In this configuration, I have been rendered the barbarian (though I have been before, as many of us have): I am a Muslim-born, middle eastern immigrant, a divorced childless middle-aged feminist with a doctorate in the Humanities. I am now the intersection of the axes of the new barbarian explicitly articulated by the Trump campaign.

In this moment of wild political uncertainty in the United States and as a barbarian myself, I am immensely grateful to be able to teach Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians, a text written in apartheid South Africa. Coetzee was eight years old when apartheid was formally instituted in 1948, and witnessed the emergence of the 1950 Population Registration Act, which registered and classified all South Africans racially into one of three categories, “white”, “black”, or “colored”, the latter which included mix-raced as well as Indian and Asian individuals. It should be noted that these distinctions were based on appearance, often dividing members of the same biological family into different racial categories. Thus, Coetzee’s ability to describe and deconstruct patterns of institutional separation and quotidian and routinized cruelties against an “other” is informed in no small part by having lived the dystopian reality of apartheid South Africa, the institutional organizational of which was largely influenced by a real-life white fraternal conspiracy called the Broederbond. It is not insignificant that Coetzee was born to Afrikaner parents and, while he openly resisted Apartheid, nonetheless was a privileged member of South African society: In this book, he beautifully relays the subtle truths about privilege and its many losses.

* * *

Waiting for the Barbarians is a mapping of colonial relationships, a philosophical challenge to the cruelties of civilization hidden behind paranoid invocations of the “other”, and a cautionary tale of privilege as itself a momentous loss.

The text is an exquisite breakdown of how the other, in this case the barbarian, is a construction informed largely by paranoia and projection. Early on in the narrative, we learn that Colonel Joll’s soldiers capture a dozen local fisherman for no other reason than they were hiding, a fact that the Magistrate characterizes as “[t]he reasoning of the policeman” (18). This reasoning to which he points is, of course, circular: The distrust of the policeman for the “other” renders any act by this “other” ipso facto suspicious. By definition, there is no benefit of the doubt for the barbarian, the truth of which justifies the expansion of the security apparatus of the empire at every turn.

Moreover, the conditions which produce “the barbarian” are the conditions mandated by the empire itself. These nomads, now prisoners, are forced into a small space in the yard, using a corner as a latrine, entirely limited in their movement to the enclosed area and fully dependent on the care of those who imprison them. Then — and here’s the kicker — the locals begin to complain about these “barbarians” because they are intrusive: “[t]he filth, the smell, the noise of quarrelling and coughing become too much….A rumour begins to go the rounds that they are diseased, that they will bring an epidemic to the town….the kitchen staff refuse them utensils and begin to toss them their food from the doorway as if they were indeed animals” (20). The other as lazy, as violent, as uncouth is a fact made of the institutions of power, not merely adjudicated by them.

Detainees in orange jumpsuits sit in a holding area at Camp X-Ray of Naval Base Guantanamo Bay (January 11, 2002). Image via Reuters File.

Thus what this scene does is reveal to the reader the patterns of subjugation, and it seems to take a mere three steps: (1) Those invested with power are taught to distrust them and imprison them because they are others/“barbarians.” (2) They impose conditions which are vile and inhuman, and limit their scope of life to satiation of immediate biological needs, and thereafter (3) justify their prejudices and the exclusion of the barbarian/other with reference to the filth and their “animal behaviors” of the other as proof of natural differences. Thus, in this scene we see the use paranoia and fear as a justification for dispossession, and dispossession as key to the maintenance of institutions of power and control. Of course, in case we missed this lesson the first time in the text, this process is repeated when the Magistrate is imprisoned (e.g., 80, 84) showing how the process of dehumanization is the one stable in the functioning of power, and where we can most clearly apprehend the vicissitudes of privilege.

The book reveals that privilege blinds one to the obvious, a sentiment eloquently expressed by a thought attributed to the Magistrate: “There has been something staring me in the face, and still I do not see it” (155). When he is imprisoned and denigrated, the magistrate is surprised, taken unawares, even as he has watched so many suffer before him: “’Why me?’ Never has there been anyone so confused and innocent of the world as I. A veritable baby!” (94). He continues a few lines later:

Deliberately I bring to mind images of innocents I have known: the boy lying naked in the lamplight with his hands pressed to his groins, the barbarian prisoners squatting in the dust, shading their eyes, waiting for whatever is to come next. Why should it be inconceivable that the behemoth that trampled them will trample me too? (94)

Operations in the Warsaw Ghetto in April and May of 1943 to empty the Ghetto and deport its remaining holdouts — men, women and children. Image via the New York Times.

This perfectly encompasses the main lesson of the novel: If routine forms of cruelty can be used against “others”, you cannot be surprised when that same law and order comes to oppress you as its other. Moreover, just as you once believed the law was just even in its violence, you cannot be surprised to find yourself alone when you desperately need the protection of others (as they needed yours). And yet, we will be surprised. The truth of privilege is both that one is blind to the injustices hiding behind the letter of the law, and caught alone the moment when the law reveals its irrationality.

The final lesson is that we need the protection of others. In his own process of being othered — through denial in prison, through torture, through ritualized humiliations that conscript the townsfolk into the process of punishment and dehumanization — the Magistrate finds himself alone, wishing he had come to know his townsfolk better and to know if they, like he, detested the things unfolding around them since the arrival of the men of the capital. Observing the cruelty he fantasizes about the kinds of people that may surround him but which he does not know, people who are as bothered by the sound of the suffering inflicted on others around them: “If comrades like these exist, what a pity I do not know them” (104). Solidarity is a cornerstone of political protection, the Magistrate comes to realize at the moment when he is already taboo. Privilege will always be a loss at the moment in which the law turns from its false promise of protection to a mechanism of cruelty, punishment, and dispossession.

* * *

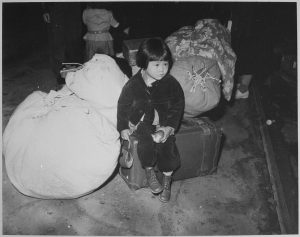

Japanese-American child with family belongings en route to California internment camp (Spring 1942). Image via U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

What the book does not let us forget is that the force of law, while real, and routinely exercised to dispossess the already vulnerable, is nonetheless localized, limited, and ultimately, fragmentary. In a political world where racism is proclaimed openly, where acts of violence are following the new empowerment of hate in America, where it is unclear what laws will be enforced and against whom in the months and years to come (not to mention the laws to passed and undone), we must remember once and repeat to ourselves daily what our own UC Irvine Comparative Literature Professor Etienne Balibar says in Politics and the Other Scene: “[t]here is autonomy of politics only to the extent that subjects are the source and ultimate reference of emancipation for each other” (10). Let us take this seriously and remember that we are the source of support and liberation for one another. We can no longer assume a caring state will help the dispossessed, that the law answers the distress of the victim of hate and violence, that the person terrorized in front of you will be saved by someone else, that calling the police will end in what you would call justice. The fact we did for so long in the face of testimony by those subjected to the cruelty of the state betrays the extent that we are also under the spell of disavowal that marks the existence of the Magistrate until he becomes “othered” (see for example, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here).

Works Cited

Étienne Balibar, Politics and the Other Scene, trans. Christine Jones, James Swenson and Chris Turner (London: Verso, 2002).

J.M. Coetzee, Waiting for the Barbarians (New York: Penguin Books, 1980).

Sharareh Frouzesh is a seminar leader in the Humanities Core Program at UC Irvine, where she received her PhD in Comparative Literature. Her research focuses on identity formation and the privileging of particular identities through an exploration of the concept of guilt. Her interdisciplinary work engages with 20th and 21st century Iranian and Iranian-American Literature, postcolonial Anglophone and World Literatures, as well as literary theory, political philosophy, and postcolonial, critical, psychoanalytic, and feminist theories.

Sharareh Frouzesh is a seminar leader in the Humanities Core Program at UC Irvine, where she received her PhD in Comparative Literature. Her research focuses on identity formation and the privileging of particular identities through an exploration of the concept of guilt. Her interdisciplinary work engages with 20th and 21st century Iranian and Iranian-American Literature, postcolonial Anglophone and World Literatures, as well as literary theory, political philosophy, and postcolonial, critical, psychoanalytic, and feminist theories.

Racism has been a part of our society for a long time and with the election of Donald Trump it makes apparent how divided the U.S. is on certain standpoints. There are some who truly think that the minorities are at fault for everything that is wrong. Coming from a family that was originally from Mexico I can understand the frustration many have with the ideas that Trump has (especially about the making of the wall on the border). The book “Waiting for the Barbarians” really does change the way one perceives barbarians to be, at the start of the book I connected the term to the “savages” outside of the empire who live their life unlike the people who are civilized. By the end of the book my perspective shifted to the barbarians being the people who were supposedly civilized.

Another interesting idea brought up by the people is that we seem to be spending so much money on prisoners, people who have broken laws in our society, and essentially pay for them to live a decent meager life in prison. Costing tax payers a lot of money, money that could go elsewhere such as helping our veterans or even using this money in other places such as schools or public facilities. So the cost of keeping prisoners in jail is quite expensive , and is also another hindrance to the people. Overall, I would like to commend the post because it gives many facts about how anyone can become a victim in the system if branded with the term, convict. There’s a show where officers scare delinquent kids into going down the right path as compared to continuing being a nuisance in society. In this show we also see what I believe to be excessive force made by the officers to “scare straight” these kids from ever entering the jail system. A small example of how people in charge of the others tend to see themselves so much higher compared to the convicts.

I agree with the authors claim of empire creating the idea of what defines a “barbarian.” In the beginning of the post, the author calls herself a “barbarian,” by America’s definition as a result from the recent election. Despite being an intellectual, she acknowledges how other peoples prejudices affects her position with society. It is a sad irony of the history of America’s prejudices against minorities, when the nation itself was built by the efforts of other groups.

I like the idea that the empire is the creator of the concept of “barbarian.” The empire supplies the conditions to administer titles to those they want in power and those they want to subdue. It is all up to perspective. I think it is interesting how you mention that non- white minorities are seen as “needed to be put back in their place,” as if white was the original intent of the nation. It’s ironic that a nation built upon non- white natives and slaves for the use of immigrants now turns to say that immigrants are bad and the cause of the trouble.

Dr. Frouzesh mentioned that in the novel, those who had power imposed inhuman conditions on “others” not only because they see themselves as superior and reference the barbarians as filthy animal, but fear is also a major reason why the barbarians are tortured and ostracized. The people who lived in the post have fear of the unknown because they have never seen barbarians, but the way that empire has portrayed barbarians, has led many to believe that they are savages and will kill everyone and everything in their path. These people only see barbarians from the perspective of empire but they are truly ignorant because they do not see what empire does to the barbarians, such as take their lands and animals, emphasizing racial hierarchy.

When reading “Waiting for the Barbarians”, I too found myself making a strong connection with the context behind the meaning of being a “barbarian”. In the novel, ideas of xenophobia are brought up through the empires’ precautions and concerns with the barbarians’ “harmful” future intentions. For example, in the beginning of the novel Colonel Joll totures two “barbarians” and demands to know their plan of conquering their empire without any actual evidence that could lead towards this particular assumption. The magistrate on the other hand, protagonist of the story, claims that he’s never seen barbarians or any evidence that support what the capital perceives them as (therefore he doesn’t use force against them). Here we have two different perspectives on people who aren’t considered to be a part of their society, one deriving from the fear of foreigners. Today, we live in a society where racially profiling people is considered a solution to some of the country’s biggest issues. To many citizens and non-citizens, the election of a man who demonstrates this frightening reality has struck fear throughout the United States. There are actual safe zones being established, to which undocumented “barbarians” can avoid deportation back to the countries they came from. This connection between a novel written in the 80’s to a society we live in today is astonishing. My family could be considered “barbarians” as they were once undocumented immigrants years back when first arriving into the country. So I have experienced first hand what this fear looks like, and for it to be happening to many families across the nation who are tirelessly contributing to the country’s success, is a tragedy. Hopefully people find a way to stay untied against dangerous perceptions and ideas of xenophobia, that could potentially bring back discrimination between the very people who make America the land of liberty.

What a fantastic post! I have to commend you on your ability to correlate the ideology that a barbarian is a construction that is mandated by the empire itself. Ultimately it is very true in a sense that it is created out of fear and I believe the claim you made is essential for everyone, not even those who are privileged, but those who live their lives through a foggy lens, and with prejudice, have to realize that the laws that do wrong to who they consider other,will ultimately do the same to them. And the U.S. needs to realize that these detainment prisons, the way they are kept, are not beneficial for those who say that they will spread disease from the degrading hygiene in the place, but also the people who are forced to be in it. If America spends so much money to keep people in there, and want them to prove to others that they can contribute to American society, then I firmly believe that we should let them have a chance beginning in the prisons, and other places, like skid row in Los Angeles.

I too thought it was amazing how Dr. Frouzesh was able to correlate barbarianism with empire itself. I also thought it was interesting how she identified herself as a barbarian (“In this moment of wild political uncertainty in the United States and as a barbarian myself…”) because it exemplifies her statement of how she differs from the majority, which a lot of us may and can relate to. Because of the different racial categories created through history itself, it is acknowledgeable of Dr. Frouzesh’s statement, that we need protection from one another. Without the protection, society could turn towards bestiality, inequality, and violence.

Dr. Frouzesh employs an appropriate comparison of the others’, or barbarians’, lifestyles to the living conditions of those in contemporary correctional facilities. To further support the distrust mentioned in the pattern of subjugation, Philip Zimbardo, a psychologist and a professor emeritus at Stanford University, proved how easy it is for individuals to assume power in certain situations in his 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment. In his studies, Zimbardo randomly assigned a group of 24 college aged volunteers to one of 2 groups, prisoners and prison guards. The guards were instructed to keep order and refrain from using all sorts of violence as the prisoners were told to sleep in their mock cells in the mock prison set up in the basement of a lab on Stanford’s campus. The psychologist and his staff were horrified as they watched the action unfold on the monitors from the room directly above. Not only did the guards assume ultimate power, they forced the prisoners to perform gruelingly physical tasks, they punished the prisoners physically for what they saw as bad behavior, and they harassed and humiliated the prisoners making them stay up until late hours or clean toilets using nothing but bare hands. As the experiment came to a close, the psychologist concluded that the subjects made stark distinctions between themselves and their counterparts in terms of their titles, their attire, and their sense of power. This fostered conformity on one side and a harsh abuse of power from the other. This nightmarish, Kafkaesque experiment led Zimbardo to conclude that those who are in a perceived seat of power will justify even the evilest, harshest acts. In the same way, as Dr. Frouzesh outlines, those in power can more easily develop a sense of superiority as they further themselves from the other emotionally, physically, and ontologically.

I think its really important to understand everybody’s perspectives and how something like the election of a presidential candidate effects people. The insight from somebody who is classified as a “barbarian” is enlightening. If it has been scientifically proven that humans are essentially genetically identical, the concept of us and them is invalid. A sense of false superiority is instilled in the people who believe they can deem others as barbarians. Which is interesting because through out this course every account we’ve had with an oppressor and the oppressed shows us how the person who deems others as the barbarian is the one embodying such brutal behavior. How ironic that person calls others barbarians, and society gives them the ability to do so.

From this blog post, there is a negative connotation associated with the privileged, depicted through how the Magistrate is unable to see the cruelty in the empire until he himself is degraded and stripped of his title. However, I do not necessarily agree that privilege is the factor that causes prejudice towards those who are deemed as barbaric or categorized as “them”. Rather, an individual’s capacity for empathy and openness to understanding the depth of another’s culture and mind are factors that distinguish between moral and immoral characters. Moreover, privilege, in certain contexts, can even open more opportunities for individuals such that they can gain a higher education, which ultimately creates a universal attitude that is open to foreign or unknown ways of thinking and behaving; those who have received a higher education are more likely to befriend those of lower or more diverse statuses than those who have received less.

As far as the role of science in understanding societal issues, I think that science is a good start but not the ultimate solution. The scientific knowledge that all humans are for the most part genetically identical is more powerful for those who are educated or study science. The problem with addressing a societal problem with academia is that knowledge can well-easily be twisted or distorted to sound appealing to exploit and misinform the uneducated masses. The “us vs. them” relationship, respectively the scholars vs. the students, can potentially be manipulated for wrong uses. Particularly, Prof. Lazo discussed how “Types of Mankind” propagated racial injustice on the basis that the species of “humanity” was actually segregated into unequal subspecies of racial appearance. Indeed, academia has too much plasticity in that it can be either do good or bad.

Rather, I believe that best way to promote long-term solution to inequality issues is through tolerance and empathy. Humans are more than scientific subjects. We are complex people with different lifestyles, ideologies, and feelings. Instead of complicating our differences further with education, we should think more simply and focus on treating others with respect and dignity. Ethics can get complicated, but I feel that a common agreement to be respectful towards others is the longest lasting solution.

As well-said in the post, now is the time to unite in solidarity for what we believe in. It is important to remember that we are not alone and that we live in a communal dynamic that thrives on widespread interconnections. We are not alone.

After reading this post, I think it is important to consider both sides of the conversation, acknowledging that there is a minority that could be affected one way or another by Trump’s election. I agree that privilege can cause blindness and cause problems, but it does not mean that whoever is privileged is also wrong. Reading this blog post made me feel as if being privileged is a bad thing, but I see it as a different perspective to look from. Just like this blog post argues that we should be looking from the minorities side and consider how “a man with no political experience” will remind the minority “of their place”, we should consider the opposite end of the spectrum. We should ask ourselves why Trump sees this certain topic this way, and see if what we find will shed light on our doubts and anxieties. I think Trump and the tons of people who voted for him have a reason for their actions, and who is to say those actions are wrong? Everyone has an opinion, and its important to look at situations from both sides.

I really liked when you mentioned how the conditions which produce “the barbarian” are the conditions mandated by the empire itself. Dehumanization regarding homelessness is an issue in today’s society. I am from a big city in Southern California that is known for having a high population of homelessness. Not only that, but recent legislation in my city has actually decreased its spending and resources on creating solutions for homelessness. Many people today have different views on the issues of homeless people. One might criticize the efforts of the actual homeless person on not stopping the trash, the public defecation, the open abuse of alcohol, heroin and methamphetamine. Others might show a bit more compassion, such as the homeless people needing mentally ill and needing guidance. Whatever your stance may be, its evident that this is an issue across the nation. Big cities tend to push homeless people into specific areas, not letting them house accordingly to their preferences and ultimately accumulating. This then leads to people complaining how they live “barbaric” lifestyles (i.e living in tents and having poor hygiene). Such viewpoints are established because cities have made it an issue in which they try to fix but ultimately has no positive impact.

This idea of “other” how you mention, I believe, cultivates more than a divide. It cultivates a mentality to not be the “other”, a mentality to strive for superiority, a mentality to create a bubble and proclaim beliefs so an individual won’t be “other.” I remember stories of immigrant, especially those of my Filipino mother, who wished to be American badly. To have privileges and opportunities that was there at here time. Sadly, when an immigrant arrives in White America, they are automatically considered the “other” based on accent, knowledge, and skin color. To them, they choose to not be “other” and strive to be “America” thus they denied this side of “other.” I saw that in the Magistrate. I can imagine him as a non-European as he does not recognize much customs of the land Joll came from. What was problematic to me in the beginning of Waiting For The Barbarian was he believed he was not the barbarian because there was sense of denial from him. He believed he was not the other and he carried the privileges as Joll did. However, his denial surprises him when he was thrown in prison. When he started to accept he was the “other.” You are right, it should not be a surprise after the results of the election yet it was because the denial people held, the belief they held that they have the same privileges and opportunities as white people, the belief they held that they have equality. As cynical as I sound, half of the U.S. citizens who are surprised by a resurgence of prejudice are like the Magistrate. They denied their “other” until someone made they realized they are the “other.”

It seems that the definition of “other” shifts depending on the time and views of a nation or empire. It also seems to become more clearly defined when a country is in difficult times, to have a scapegoat for pre-existing issues. I think that’s why Waiting fo r the Barbarians was hard to read for me, because it was easy to apply the position of the barbarians to many groups of people, and the time period could have fit in many places across history.

In regards to the other replies, I think science could have an effect on racism, but there have been times in history when scientific studies were strongly influenced by racist beliefs and set out to ‘prove’ them. Scientific racism has been used to justify superiority of one race over another and even justified racism.

After hearing the election results, my heart broke. It’s frightening that it’s 2016 and we are still divided by race, gender, and religion preference. I personally thought we were past this stage, but the election results have proved that a presidential candidate can openly mention racists comments and that he has many followers/supporters despite the cruel things he’s said. We are constantly battling this idea of ‘us vs. them’ but unity is what we need. I’m curious to see how the next 4 years will play out and I hope it won’t be as bad as we expect it to be–– especially since many of those in minority communities are fearful.

The Waiting for the Barbarians book was a tough read for me, since it made me feel disgusted of the main character at points for treating and seeing women the way that he does. I had a hard time understanding the Magistrate in the novel, he seemed to hate the system but didn’t hate it enough to stop being a part of it. So, I think it’s crucial that our young voices start to do more than just tweet about our frustration in the dividing of our nation– and stand up against it to promote change. Although some people state that protests “will not change anything”, I believe that they are wrong. I think that we need to constantly give voice to the suppressed. We need to join forces to take down this barrier of characteristics falsely deeming superiority to others. We need to constantly participate in peaceful protests and put the idea in everyone that we are not going to tolerate hate to minorities.

As for the replies mentioned above, I think it’s an interesting claim to make that science and rational thought will end racism. I don’t know if there will ever, in fact, be an absolute END to racism, but that we can only try to get closer and closer to eliminating it. Science has helped us progress greatly in efficiency but I’m not sure if scientific fact will reverse the conditioned social thought that one race/gender/religion is better than the other. I think it’s crucial that we help develop a positive, inclusive way of thought in our future generations.

Sarah, I agree that as time has passed, most of us would think that we would be passed all the racism and hate towards one another but unfortunately it is still present, not only in our country but around the world. The election of Donald Trump makes many people wonder who could actually vote for such a man who promotes hate and racism and who also seems to be trying to dividing the country instead of bringing us together. Because of these election results, many people are now in fear and do see themselves as barbarians but in fact it shouldn’t be like that. I believe that science can help stop racism, but I think coming together and turning away from violence can bring better results.

One statement in this blog post that really drew my attention was the mention of members of the same family being divided into separate racial classes. It reminded me of the colonial rule of the East India Company, and how Jawaharlal Nehru, who went on to become the first Prime Minister of India, was once told that his sister was ‘too white’ to be an Indian by Company officials.

Students in my Biological Sciences 93 course also very recently discussed how skin color is influenced by multiple genes, and how offspring could have skin color very different from that of their parents. Thus, I think Science and rational thought is the key to ending racism.

I do think it is interesting to try and approach the issue of racism from the perspective of science. On the one hand, science tells us that contrary to the beliefs of many, there is very little genetic difference across the races. Below our skin — the color of which seems to ignite so many ridiculous issues — our genes look the same. Humans are too recently evolved to show any kind of racial genetic grouping. Race is simply a social construct.

On the other hand, however, science is also involved in the concept of “insiders” versus “outsiders.” “Us versus them” is an age-old conflict not unique to humans. Across the animal kingdom, there are biological benefits to categorizing individuals as “one of us” or as an “other,” the biggest being security. Competition for scare resources is something that helps solidify groups, and once something is identified as worth fighting for — be it water, food, shelter, etc. — anyone outside of an individual’s group is an enemy. In this sense, I think at a very base level, science contributes to prejudice and racism. Society and culture only aggravate these problems.

Considering this, a scientific perspective alone won’t save us from group conflicts. I think that ultimately (no matter how cheesy it sounds) compassion and kindness are the only things that will allow us to see past our differences. Empathy is key to preventing cruelty.