Why might it be valuable for our students to read race and gender together to understand the power structure of empire in Aphra Behn’s novel – not only in the plight of handsome prince Oroonoko and his beautiful Imoinda as individuals, but also for the economic and social structure of the slave trade? What could students learn about reading both categories together, rather than just for one? The instability of the woman narrator’s voice in her description of a slave market in the triangle trade is a useful place for students to begin understanding this intersection:

Those then whom we make use of to work in our plantations of sugar are Negroes, black slaves altogether […]. Those who want slaves make a bargain with a master or a captain of a ship, and contract to pay for them when they shall be delivered on such a plantation. So that when there arrives a ship laden with slaves, they who have so contracted go aboard and receive their number by lot; and perhaps in one lot that may be for ten, there may happen to be three or four men, the rest women and children; or be there more or less of either sex, you are obliged to be content with your lot. (12-13)

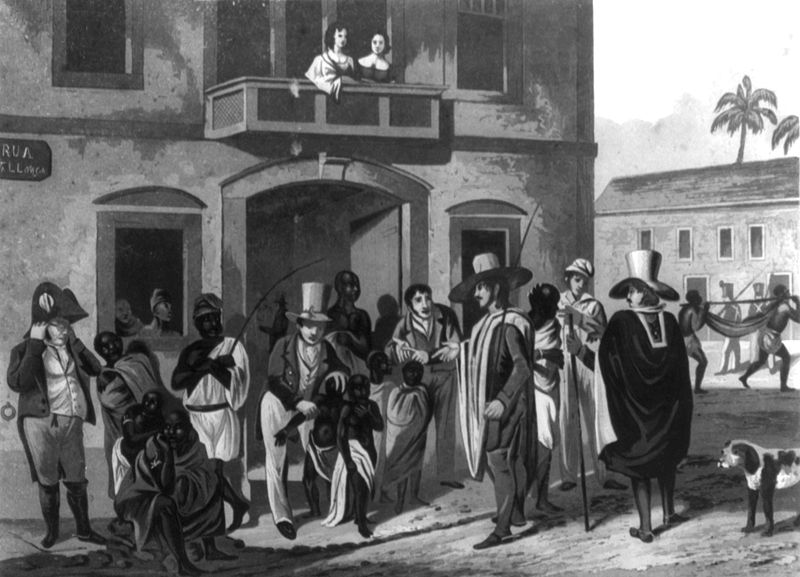

In lecture Prof. Jayne Lewis spoke about keywords that locate the narrator among white slaveowners and buyers by starting off in the first person: “we make use of” the Africans for the sugar plantations on which she was a guest. She establishes some distance from “those who want slaves” as employers, though her visit benefits from slaves’ “work”. “They” as buyers “bargain,” “contract,” “pay,” terms that continue to identify them in the third person: here, slave buyers are white. They are also most likely male, as illlustrations indicate, and ownership makes probable. The recently licensed commerce to use Africans for profit seems almost fair: in this marketplace, buyers do not know who will be in any “lot” they have contracted for: perhaps “three or four men,” with as an afterthought “the rest women and children”? (For immediate profit in the sugar fields, the men are singled out.) But this poses a moral problem that the narrator cannot solve in first and third person narrative: in the key moment: “you are obliged to be content with your lot.” The decision may be a choice of the captain or master, but the word “lot” suggests it is something you accept as some sort of economic if not social contract. But who or where are “you”? You are a buyer – context makes it clear that you are not a slave, because slaves have no ability to contract and therefore no obligation in this situation. The slave market is a scene of identity shock. Tamara Beauchamp suggested to me that the ordinarily feminized reader of the romance, the ‘you’ in the passage, may be in an identificatory relationship with the slaves, but I don’t read the “you” that way. However, I would agree that there is irony floating around here: as a woman, the narrator is obliged to be “content with her lot” in some ways: she cannot rescue the lovers, much as she sympathizes with them. But neither can she articulate the relationship of her realistic scene to her romantic tale of the lovers. Perhaps this break is signaled by the sudden move to “Coromantien,” the first word of the next paragraph, where the narrator reclaims her authority.

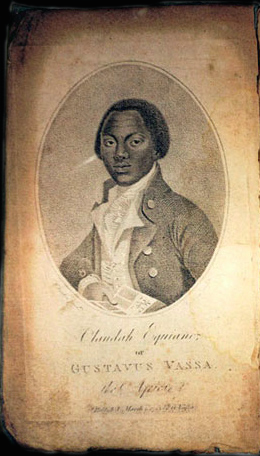

Frontispiece to Irish edition of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equino (Dublin, 1791)

Among secondary sources for research on the intersection of race and gender, I would recommend Laura Brown, in her Ends of Empire: Women and Ideology in Early Eighteenth-Century Literature (Cornell, 1993). Brown does not use this passage, but she takes Oroonoko as “a theoretical test case for the necessary connection of race and gender.” Brown argues that the “reductive normalizing” of the romantic narrative must be read together with the experiences of the slaves “because they are oriented around the same governing point of reference, the ubiquitous and indispensable figure of the woman.”

For compare and contrast work, I would recommend The Interesting Life of Olaudah Equiano, Written by Himself; here the slaves are divided into “parcels,” or as he later says “lots,” and the buyers rush to “make choice of the parcel they like best.” But Equiano, an ex-slave, writes from the point of view of the “terrified Africans,” men, women, and children. The question of fairness here is seen from the slaves’ point of view. (I would agree that Equiano’s task is different as a man writing in 1791, but that too would be worth comparing.) Behn’s narrator could perhaps glimpse the possibility of describing the slave market this way, but her use of first-, second-, and third-person pronouns shows that she cannot yet articulate or integrate it into the story.

Works Cited

Behn, Aphra. Oroonoko. Ed. Janet Todd. London: Penguin Books, 2003. Print.

Brown, Laura. Ends of Empire: Women and Ideology in Early Eighteenth-Century Literature. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1993. Print.

Equiano, Olaudah. Interesting Narrative and Other Writings. London: Penguin Books, 2004. Print.

Vivian Folkenflik is an emeritus lecturer in the Humanities Core Program, where she taught for over three decades. She is the editor and translator of Anne Gédéon Lafitte, the Marquis de Pelleport’s novel The Bohemians (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009) and An Extraordinary Woman: Selected Writings of Germaine de Staël (Columbia University Press, 1992). She is also the author and archivist of our program’s institutional history at UC Irvine. Her thought and teaching have been at the center of many cycles of Humanities Core, and she continues to act as a pedagogical mentor for seminar leaders in our program.

Vivian Folkenflik is an emeritus lecturer in the Humanities Core Program, where she taught for over three decades. She is the editor and translator of Anne Gédéon Lafitte, the Marquis de Pelleport’s novel The Bohemians (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009) and An Extraordinary Woman: Selected Writings of Germaine de Staël (Columbia University Press, 1992). She is also the author and archivist of our program’s institutional history at UC Irvine. Her thought and teaching have been at the center of many cycles of Humanities Core, and she continues to act as a pedagogical mentor for seminar leaders in our program.

I find it interesting how race and gender constructs help shape slave trade throughout years. I do agree that in this passage the role that gender and race play help us to understand how there are not only divisions among race and gender but divisions among age as well. For a slave owner, male slaves are more practical because they get more work done. Females are less valuable than men, and children less valuable than women. It brings light to the fact that no matter what gender, race, or age you are you will most likely be oppressed if you do not fit the ideals of the “Mythical Norm.”

Although very unlikely for a woman to be a slave buyer during the time this novel was written, I do believe that the “you” that Behn is referencing is intact a female.

With the belief that the “you” is referring to the female slave buyers, we can see how gender plays a role in divisions of class. Usually when a slave buyer is a wealthy man, he is able to pick which slaves he wants by offering more money, this is not the case in the novel. With the slave buyer being female, she has no say in who is a part of her “lot” or not, she has to agree with the male slave seller.

Professor Folkenfilk, I believe this to be a solid analysis of this passage in Oroonoko. While I agree with you that both gender and race are critical in understanding the narrator’s voice in terms of the slave market, I disagree with the claim that “neither can she articulate the relationship of her realistic scene to her romantic tale of lovers.” In fact, I believe Behn is able to tell her romantic tale of lovers while conveying the horrors and reality that the slave trade is a horrid concept; she uses both gender and race to display how awful the slave trade was in terms of seeing black people as pieces to the “lot” in which they come in, signify the race aspect of the slave trade. Not only does she address race, but she also explains that women and children made up the rest of the “lot” and that ‘you’ as a reader are to be satisfied with the “lot” as a whole- as if women and children are valueless. Not only are they valueless because of their gender, as women, but they are valueless because they are black women. Later in Oroonoko, Imoinda is murdered by Oroonoko because he believes her, as a black, child-bearing woman to be better off dead than a slave, which further highlights the horrors and realities of the slave trade, while exemplifying both gender and race, all while articulating her romantic tale of lovers by Oroonoko having the courage to murder his own wife so that she may be in a better situation in spite of his love for her.