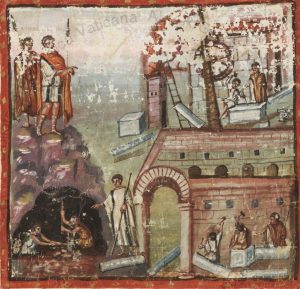

Aeneas and Achates entering Carthage, as pictured in the Vergilianus Vaticanus folio 13r. Image reproduction courtesy of the Apostolic Library, Vatican. All rights reserved.

This post was originally published on September 29, 2016.

For educated people in the European Middle Ages, the Aeneid was probably the most important piece of literature next to the Bible: it was the greatest epic poem written in Latin which was the standard language of learning across Europe. It is no accident that Dante chose Virgil to lead him through the Nine Circles of Hell in Inferno. As a scholar of Late Roman and Medieval European literature, then, the Aeneid is an important book for me to be pretty familiar with.

One of the most important questions I have to ask myself at the start of any research project – but particularly about such an old text – is whether or not I can trust the edition I am working with. This is obviously a problem when we are reading in translation, but even if we were all reading the Aeneid in Latin in Humanities Core, we would still have to ask… is this really what Virgil wrote? Here’s why.

The version of Virgil’s Aeneid that we are reading is an excellent translation by Robert Fagles. But let me ask you a question: where did he find his text to translate from? The Aeneid was written between 29 and 19 BCE, but printed type was not introduced into Europe until around 1440 CE. How did the poem exist between when Virgil composed it and when Fagles translated it into English for us?

You may be surprised to know that there is no single “original” version of the Aeneid from 19 BCE that all of our printed copies comes from. Virgil, like most Romans, probably wrote his works on papyrus sheets or scrolls. Now in a dry environment like Egypt, papyrus can last a very long time, but in a more humid climate like Italy, a papyrus scroll would begin to fall apart within a century. This meant that scribes had to make new hand-written copies (manu scripta in Latin) of important texts like Virgil’s works in order to preserve them. Almost all of these scrolls turned to dust long ago.

Near the end of the Roman Empire, however, it became more common for scribes to write on a new material made of dried and stretched animal skin called parchment, and to bind these pieces of parchment together into a codex: what we would call a book. The Getty Museum has produced a short but excellent video about how manuscripts were made.

Parchment is far more durable than papyrus, and it is no coincidence that the seven earliest versions of the Aeneid that still exist today are parchment copies from around the year 400 CE, more than four centuries after Virgil’s death (Courtney 13). Thanks to a number of digitization projects at archives and libraries around the world, you can actually look at digitized versions of some of these manuscripts online, like the Vergilius Vaticanus and Vergilius Romanus, both preserved at the Apostolic Library of the Vatican. All of these surviving manuscripts are incomplete, damaged, or compromised in some way. There were in all likelihood many other parchment and papyrus copies from this early date that were completely lost or destroyed during the violent dissolution of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth and sixth centuries.

Even if we had a totally complete, undamaged copy of the Aeneid from 400 CE, however, it still might be affected by scribal errors. Since each copy was made by hand, it is easy to see how scribal mistakes, mis-readings, and other variations could grow and become compounded in later copies. It is unknown how many copies of copies were made between Virgil’s own text of the Aeneid and these seven “witnesses,” but the text of all seven differ from each other. Some of these variations are clearly mistakes or corruptions of the original text; other differences between the manuscripts are harder to adjudicate, and it takes scholarship known as “textual criticism” to be able to tell which text is closer to the original. Sometimes, mistakes in the manuscripts will not be noticed for more than a thousand years.

Let me give you a few examples to illustrate what I mean. Take the scene from Book I (lines 423-29) when Aeneas and Achates have entered Carthage and are marveling at all of the city construction projects as they climb the hill to the top. Fagles translates this as follows:

The Tyrians press on with the work, some aligning the walls,

struggling to raise the citadel, trundling stones up slopes;

some picking the building sites and plowing out their boundaries,

others drafting laws, electing judges, a senate held in awe.

Here they’re dredging a harbor, there they lay foundations

deep for a theater, quarrying out of rock great columns

to form a fitting scene for stages still to come.

(Book I, lines 513-19, pp. 61-62)

If we look at our manuscript witnesses from the Vatican, we can see that they disagree about a few of the details. Neither one is totally correct; instead, both have to be compared because they equally point back towards their lost original exemplar. Since it may be difficult to read the manuscripts, I’ve written out a transcription of the two texts:

Detail from Vat. f13v [MSS Vat. lat. 3225]. Image reproduction courtesy of the Apostolic Library, Vatican. All rights reserved.

INSTANTARDENTESTYRIIPARSDUCEREMUROS

MOLIRIQUEARCEM·ETMANIBUSSUBUOLUERESAXA

PARSOPTARELOCUMTECTOETCONCLUDERESULCO

IURAMAGISTRATUSQ·LEGUNT·SANCTUMQUESENATUM

HICPORTUSALIIEFFODIUNTHICLATATHEATRIS

FUNDAMENTAPETUNTALIIIMMANISQUECOLUMNAS

RUPIBUSEXCIDUNTSCAENISDECORAALTAFUTURIS˙

Detail from Rom. f89v [MSS Vat. lat. 3867] Image reproduction courtesy of the Apostolic Library, Vatican. All rights reserved.

INSTANT·ARDENTES·TYRII·PARS·DUCERE·MUROS

MOLIRI·QUE·ARCEM·ET·MANIBUS·SUBUOLUERE·SAXA

PARS·APTARE·LOCUM·TECTO·ET·CONCLUDERE·SULCO

IURA·MAGISTRATUSQ:LEGUNT·SANCTUM·Q:SENATU

HIC·PORTUS·ALII·EFFODIUNT·HIC·ALTA·THEATRIS·

FUNDAMENTA·LOCANT·ALII·IMMANIS·Q:COLUMNAS

RUPIBUS·EXCIDUNT·SCAENIS·DECORA·ALTA·FUTURIS

Notice that in the third line Rom. has the word aptare, while Vat. has optare. Fagles (or, rather, the edition of the Latin text that Fagles translated) chose to use optare here, since he translates the line as “some picking the building sites.” If he had translated aptare, it would have said something like “fitting the building sites” instead. Yet he chooses against the Vat. text two lines later: the workers “lay foundations / deep for a theater,” matching alta theatris / fundamenta locant. Had he followed the Vat. text, he might have translated lata theatris / fundamenta petunt as “they seek foundations broad for a theater,” which doesn’t make quite as much sense. Still, some editors choose to read the text this other way (cf. Conington 75). Switching alta for lata is probably the scribal equivalent of a “typo.” Mixing up locant and petunt, on the other hand, is harder to explain. We moderns are not the first to notice this discrepancy, however: if you look closely, an early medieval reader has put a little mark that looks like a percentage sign (%) over the word petunt, and noted a correction “LOCANT” in the left-hand margin.

Even if all the manuscripts agree, however, this still doesn’t mean that we have access to the original text as Virgil wrote it: it just means that all of the manuscripts we have are descended from a common source which may not be Virgil’s original. In this same passage given above about city projects from Book I, you may have noticed something strange. The poem focuses here on the physical work of building a city, except for one line. It may not strike you at first, but the central line about “drafting laws” and a “senate held in awe” doesn’t totally match its surroundings, does it? In fact, even though this line appears in this spot in all seven witnesses, some readers from the classical era to the present day doubt that this line was in the original poem, and believe that it was added by a later scribe.

Why should you care about such minutiae as this? There are at least two reasons, the first more general, and the second more specific for Humanities Core. First, what I have said above about how texts change from manuscript to manuscript does not just apply to the Aeneid, or to ancient literature, or to things written by hand. In fact, all texts are subject to this kind of corruption and variation, even texts that might seem totally modern and well-established, which is why many important books are released in critical editions even if they were written in America in the 20th century. If you don’t believe me, take a look at the interaction between Bilbo and Gollum in the first edition of The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien compared to the second edition that came out after he had written The Lord of the Rings. There are also differences between the British and American versions of the Harry Potter series. Needless to say, if there are variations in these texts, there are also variations in the various printings and editions of books like Waiting for the Barbarians, The Tempest, and every other thing you will read this year in Humanities Core.

This brings me to the second reason you should care about textual criticism. Let’s say I was writing a paper about the Aeneid and I wanted to make the claim that for Virgil there was an implicit connection between the physical foundation of a city and the institutional foundation of its laws. I might want to use this passage from Book I, since it shows the senate and the laws coming into being at the same moment, even in the same sentence, as the pillars and stones of the city. If I simply quoted this section, however, and my reader knew that the line about the laws was probably added later (or taken from a different section of the poem, see Campbell 161), they could trash my argument, saying it proved nothing because the line wasn’t original to the poem. If, on the other hand, I incorporated textual criticism into my research, I could argue that constructing the law and constructing the city were tied together in the Roman mind, and that this is demonstrated by the fact that some Roman editor or scribe added the line about the laws and the Senate to the original, and most people after that either didn’t notice it as strange or felt that the poem was better or more interesting this way. My argument has changed and deepened from one about Virgil’s psychology – something that is ultimately impossible to prove – to one about critical reception and the history of the Aeneid within Roman culture.

Works Cited

Campbell, A. Y. “Aeneidea.” The Classical Review 52, 2 (Nov. 1938): 161-63. Print.

Conington, John and Virgil. The Works of Virgil with a Commentary by John Conington, M.A. Vol. II. London: Whittaker & Co., 1876. Print.

Courntey, E. “The Formation of the Text of Virgil.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 28 (1981): 13-29. Print.

Virgil. Bucolics, Aeneid, and Georgics of Virgil. Edited by J.B. Greenough. Boston: Ginn & Co., 1900. Digital text available online at The Perseus Project. Accessed 30 Aug. 2016. Web.

Virgil. The Aeneid. Translated by Robert Fagles. Introduction by Bernard Knox. New York, Penguin Books, 2006. Print.

Ben Garceau is a scholar of medieval literature with particular interests in early Britain, translation, and critical theory. He received a dual Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and English from Indiana University in 2015. His article “Passing Over, Passing On: Survivance in the Translation of Deor by Seamus Heaney and J. L. Borges” is forthcoming in PMLA. When he isn’t leading seminars in Humanities Core, he likes hiking, working on his science fiction novel, and digging through record shops in Los Angeles.

Ben Garceau is a scholar of medieval literature with particular interests in early Britain, translation, and critical theory. He received a dual Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and English from Indiana University in 2015. His article “Passing Over, Passing On: Survivance in the Translation of Deor by Seamus Heaney and J. L. Borges” is forthcoming in PMLA. When he isn’t leading seminars in Humanities Core, he likes hiking, working on his science fiction novel, and digging through record shops in Los Angeles.

This post was insightful and I thoroughly enjoyed inspecting certain differences between the different additions of the Aeneid. Prior to reading this post I questioned the ability of one to translate such a tale in an accurate manor, and I enjoyed going through the process of finding subtle differences between modern day and ancient translations of the same text. The statement “all texts are subject to this kind of corruption and variation” truly enlightened me to the different variations in which a text may be misshapen in subtle ways, that I had never quite thought about before. this was a great post and I will keep this all in mind as I read other texts.

Thanks Sophia! I’m glad it got you to think more critically about the texts you read and how they are produced.

This blog gives an interesting insight in how time and human error can alter work to the point the edition of the Aeneid we are reading could lose some of its early meanings. Even translating the Aeneid is a form of language barrier since some words have multiple meanings and could reference idioms or Roman culture in its native language. Literal translation hardly is sufficient in understanding the text. The blog also mentions this language barrier in Fagles decision to choose to translate between two words word optare or aptare in different editions, two words that change the meaning of the sentence. This term correction represents the inaccuracy that Aeneid could have collected over the centuries and the accumulation of mistakes by scribes. It could have been that a scribe decided this word better fits the context and decided to add his own opinion to the Aeneid or made a typo error. In addition, it also points out how editions become different in time as versions are compiled. With modern technology, digitization helps prevent the confusion of multiple editions and eliminate the possibility of human error. With the Aeneid, the difficulty of having multiple copies and books give it an odd timeline of information yet the information is not to be discredited since the survival of the text has much to do with the importance it held to the people who sought to restore and preserve it. In one aspect, it could prove an aspect of Roman culture and give light to the work as a whole.

Well put! I’d add that sometimes the “mistakes” can be just as interesting as the original version, and sometimes when people “correct” the text, they end up with something totally wrong. It’s a balancing act, one that takes a great deal of knowledge and expertise. If you are interested in the science of textual editing, you can find more information here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textual_criticism

I’m really glad I took the time to read this. I had a vague sense that there were some translation issues in the epic, but I would’ve never assumed that the translation gap would be as significant as you clarified for us. I figured it was merely the result of Fagles translating Virgil’s original work into an English edition of the Aeneid. It’s crazy to think that there’s so much room for error during the centuries in which the epic has been recited and transcribed over and over again. I know I’ve definitely had a firsthand experience when it comes to translating English to Spanish when I’m working with Spanish Speakers. Sometimes it’s a bit tricky to find the exact words you want say, and usually I just choose to simplify the message I want to get across. It really makes you wonder how much context was lost in translation. It’s something to make a note of as I go back and try to analyze parts of the text for deeper meaning. I like that you opened up the discussion to apply it to more than just the Aeneid, it’s definitely worthwhile knowledge to keep in mind as we progress with our readings throughout Humanities Core this year.

Thanks for your thoughts Briana. It’s true that context often gets lost in translation, but that is one of the reasons we study literature in the context of its history, so that we can try to fill in the gaps. We may not be able to know the original completely, but we can get pretty close. It also means, since history keeps moving forward, that new translations and new scholarship is always needed to interpret texts for new generations.

I feel that this is one of the most interesting analytical posts I have read in a long while. Your blog post truly gave me a new perspective of the Aeneid I do not think I would have formulated on my own. I have always believed language is an extremely important part to any aspect of life, but I had never really considered it in terms of literature. Not only did your perspective allow me to view the Aeneid is a new manner, but other novels I have read in the past as well, including the Harry Potter series. I believe I was able to understand your post well due to your inclusion of visual references from the Aeneid’s previous versions as well. I also found it extremely important to mention how an argument can be debunked due to the fact that we will never know what Virgil’s original text was. I feel that this can be applied to any form of writing as well in the aspect of meaning. Unless we have a direct quote from the writer, one can never be sure if a certain interpretation was meant to be implied by the text.

I agree with you for the most part, Paty, and it is important to keep in mind how texts change over time as they are read and passed down by generations of readers. But I would disagree with the idea that we can debunk everything unless we have a direct quote from the original author. First of all, any direct quote from the original author is also subject to the process of textual corruption, so that cannot be trusted either. Instead, I would say that what we do in the humanities is interpret, and that interpretations can never be known to be entirely true and infallible, but that some interpretations are stronger than others if they are based on good evidence and solid arguments. Thanks for your comment and insights!

Before reading The Aeneid, I believe a lecture by Professor Zissos had reserved a specific slide that discussed the importance of the accuracy of the text that was translated by Robert Fagles. This post mentions “Since each copy was made by hand, it is easy to see how scribal mistakes, mis-readings, and other variations could grow and become compounded in later copies” (Garceau 7). Learning that this is true for not only Virigil’s work, but possibly all types of literary works I encounter on a daily basis was striking. With manuscripts that have been translated over generations, we find that scribes may have altered aspects of the piece in order to fit within their own ideology. We may never know what is the truth of such works and or accounts. This is most evident in two different accounts of “Pyrrhus’s Victorious Defeat” by two different authors: Plutarch and Paulus Orosius. Though we can confirm that the war happened, you must take into account that both were written by two different men from different generations. Plutarch was a Greek biographer whereas Orosius was a Calchedonian priest; therefore, the difference in backgrounds and ideological bias’ could have influenced the interpretation of the war.

That’s right Jan, and this is part of what makes historical research so confounding but also so interesting. We don’t necessarily have a single version of history, and our sources often disagree. So it is up to us to decide which accounts to favor over others, and how to account for biases. In many cases, it makes more sense to talk about histories in the plural.

Before reading this post, I would never have thought that such subtle changes through generations of the same text could change the original meaning so much. Evidence is key when posing arguments especially in Literature and I agree with you that without evidence that comes from the original source, you cannot conclude anything about the mentality of the original author and what he or she was thinking. Even though we can derive information from what the scribe’s were thinking when making these subtle changes, the text becomes the scribe’s thinking, which saddens me that since there are no original version’s of Virgil’s Aeneid left, we can only analyze its derivatives which are developed by scribes generation after generation. On another hand, I have a question. Lets say, I’m trying to argue a point from Virgil’s Aeneid and I find stronger evidence in one version of text as opposed to others copied in different times. Could I use evidence from different versions of the text, handpicking ones that support my argument the strongest? Or will that just make my arguement ineffective due to confirmation bias.

I think it depends on the kind of argument you want to make, Peter. Even if there is disagreement among manuscript sources, it is important to remember that most people did not compare between two or more sources, so most readers only ever read a single version of the Aeneid. If a library had a copy of the book with a particular tradition of variants, the people who read that version would take it to be the correct version of the poem. This might change your argument from one about authorial intention to one about reader reception and a school of interpretation.

wow i honestly never thought about the possibility that i wasn’t reading Virgil’s original work! The fact that translating can sometimes do that to works makes sense because, when you’re translating it’s easy to see that not all words are the same in all languages and that you have to word something differently to make it work. it’s very hard to transfer something from one language to another without changing a few things because they don’t make sense if you don’t. Also, after something is used so much it’s normal for it to change along the way, even if it’s not on purpose. Maybe the books we read aren’t the same as what the original author wrote but at least we know they have the same ideas.

At least we hope the translations have the same ideas! Sometimes a translation can be very different from the work it is based on. In the Harry Potter books, for example, did you know that a lot of the characters have different names in French? Neville Longbottom, for example, is Neville Londubat, and the school they go to is not Hogwarts, but Poudlard. Things get even stranger in translations between more distantly related languages, or languages that are understand to be in some kind of power hierarchy. The orientalist translations of books from languages like Sanskrit and Hindi into English can be wildly different than the originals.

After reading through your post, I can wholeheartedly say that I agree with the idea that texts (especially older ones) lose some type of “validity” as translations and scribing errors take place. However, in relation to the work of Virgil, I feel that these factors definitely shouldn’t be a deterrence when trying to establish whether the information provided is “trustworthy”. While it is true that different versions of the book contain slight modifications to the lettering, they are both equally as valuable as one another. Why is it that we have decided that the words of Virgil are in any sense greater or of more worth than that of the scribes? Doesn’t the example provided also give us insight to how people (or at least the scribe in question) viewed laws as fundamental of Roman empire building? ALso, in spite of there being a pretty significant gap between the original work and the first surviving copies, the works thereafter have relatively kept the same meaning; Who’s to say that the original “message” of the work was diluted in four centuries? Classicists of today work solely based off of these types of texts and have developed a canon of Rome that has been consistent for even longer. When one thinks about it, the need for an “original” copy under these circumstances is not entirely necessary. While it would be nice to see Virgil’s original work- word for word- in the grand scheme of things, there isn’t much of a difference. We are still interpreting a work, which in it of itself can lead to other, more prevalent erroneous points.

I totally agree Wilfredo. And I am glad that my blog has prompted you to doubt whether “originals” are more important than later versions or translations. Since originality is almost never really accessible, it may be more useful for us as scholars to focus on interpretation itself.

One thing about your blog is that you are certainly not mistaken. We can never be too sure about history as we did we were not present as it was happening , i like your examples of modern literature themselves being tampered with such as The Hobbit and Lord of the rings. It really makes you wonder that if a novel as current as that can be altered with all the technology we had in the 20th century whats to say that the Aeneid which was produced thousands of years ago has not been altered far more then just the inclusion of the senate. Which brings me to my main question, if we are at the mercy of the translators which were usually the elite how do we know know how the working class and peasants perceived or understood the Aeneid? i ask because the working class or peasants is rather what most of the human population is now such as before.

Hi Steven, great question! The answer is that, unlike today, in the Roman Empire most people were not literate, so most people would have never read the Aeneid. Most children were educated up to a point, learning the shapes of letters and basic arithmetic, but the study of literature was reserved for the upper classes (although there were also highly educated Greek slaves in patrician households). It is possible that plebeians may have heard the Aeneid read aloud, or heard other versions of the story in an oral tradition, or even seen painted or carved images of the story. On a side note, do we have any evidence from the poem that Aeneas himself is literate? There is a scene where he sees the depiction of the fall of Troy on the carved doors of Carthage, but there he is looking at images, not words. You might look at Oliver Berghof’s blog post about this passage: http://sites.uci.edu/humcoreblog/2017/10/16/sunt-lacrimae-rerum-et-mentem-mortalia-tangunt/

Very interesting! It’s fascinating to think that different translations can change the interpretation of a text. In my discussion class, we looked at a more contemporary example, which was a rendition of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air theme song. After being translated through every language available, the English version at the end was incomprehensible as compared to the original version. Is there truly an appropriate way to fix this sort of “language barrier” that occurs over many years?

That sounds like a lot of fun, sort of like the game of telephone I played when I was a kid. I don’t think there is any way to fix this, aside from having people who know a lot about the language and time period in which something was written to make educated guesses about what the earlier versions of a text may have been.

This piece was very fascinating to read. The making of manuscripts is amazing. The precision it took to write and then draw out the pictures that tell us a story. Today many people use calligraphy that is very much so related to what they were doing back then. Words get lost in translation all the time. Through speech and writing. We all have different ways of interpreting different phrases, especially from one language to another. It happens a lot to me when I am talking to my mom in Spanish. When I can’t think of the word I am trying to say I often end up using a different word that doesn’t really grasp the meaning of what I am truly trying to say. This will continue happening for the rest of time, I presume.

Have you ever heard of the phrase “lost in translation”? That’s a very normal way of thinking about passing information from one language to another, that something always gets left behind. As you say about talking with your mom in Spanish, sometimes the words don’t match up exactly, or you can have different expressions in Spanish than in English. Another way of thinking about it, though, is “found in translation,” where even though you can’t get across the precise meaning of something in one language, you can recreate the meaning with a slightly different outlook or slightly different form in a new language. So, instead of thinking about it as loss, you can think about it as an opportunity for something new.

Wow! I can’t believe that it never occurred to me while I was reading the Aeneid that the copy of the book I was reading and studying was probably not the same one that Virgil wrote around 19 BCE to 29 BCE. This is similar to the children’s game of “Telephone,” where a group of kids sit in a circle and one of them begins the game by whispering to the person sitting next to him on his right something. That person continues the game by whispering the same thing the previous tells him to the person on his right, and this cycle keeps going until the last person. The goal of the game is to end up with exactly the same sentence or phrase that the first person whispered. However, this almost never works out! I remember vividly in my 3rd-grade class, we played this game and our teacher gave us an incentive. She told us that if the sentence or phrase that she tells the next player comes out exactly the same after gone through the butchering of 23 kids, we would all leave five minutes early for lunch. Of course, even with this incentive, her phrase, which was about her favorite oatmeal cookies, came out about puppies and therefore we all left for lunch at the usual time. On a more serious note, this is idea is a critical part of a book as changes in the wording of the book alters our perspective of the argument of the author. After reading this insightful blog post, I will be sure to think critically about whether I can trust a book that I am studying, especially if the book is an older one.

While it doesn’t take account of various competing manuscript accounts like you do, Ben, another potential resource is the Vergil Project, which offers an on-line hypertext of the Latin text linked to interpretive materials of various kinds. As their project description reads, “These include basic information about grammar, syntax, and diction; several commentaries; an apparatus criticus; help with scansion; and other resources.” Thanks to HumCore seminar leader Amalia Herrmann for sharing this great resource.

http://vergil.classics.upenn.edu/vergil/index.php/document/index/document_id/1

Thanks Larisa! So long as we are thinking critically about writing and collaboration, we might also consider the drafting process as an extension of this. Critical editions of modern works also take account of any early drafts, typescripts, and corrected proofs which have been preserved in rare book and manuscript libraries. These drafts can show that the steps between the author’s first sketches and final publication often involve a great deal of input from people like publishers, agents, editors, censors, even proofreaders and typesetters. In some cases, the editors of critical editions may discover that a censor or publisher has changed or completely deleted sections of the text without the author’s consent. In others, an author will gladly take criticism and change large sections of plot, character, style… you name it. With so many cooks in the kitchen, authorial intent can be very hard to pin down. But that also means that even great works of literature almost never come to the genius poet fully formed: just like our writing, or that of our students, an author’s draft typically benefits from the drafting process and peer review.

Such an interesting post, Ben! In another life, I was likely a parchment stretcher/scraper! I like that your account of the transcription process puts the notion of originality into question, thereby challenging the most important premise that protects intellectual property. As you say: this question of originality doesn’t only apply to ancient manuscripts. It applies to the texts we read every day, texts of every medium and genre! In that way, you touch upon many of our present conversations about writing: on the ways that collaboration shapes the meaning of texts and the ways that medium determines our reading experience. Cool! Thanks!