Kamau Brathwaite, image from New Directions Books

Someone called Edward Brathwaite makes a brief appearance in Roberto Fernández Retamar’s famous 1974 essay “Caliban: Notes toward a Discussion of Culture in Our America.” Like Caliban in Aimé Césaire’s play A Tempest, Edward Brathwaite later changed his name. But whereas Césaire’s Caliban demands that Prospero “call me X” (20), Brathwaite chose the name Kamau. It was suggested to him by the grandmother of the Kenyan novelist and theorist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who currently teaches at UC Irvine! The name Kamau itself ultimately comes from the east African Kikuyu language and is said to mean “quiet warrior.”

Brathwaite’s journey from a highly conventional English name to a subtle and empowering African one is a journey toward an ancestral identity that holds the possibility of self-determination. A similar journey was taken by Brathwaite’s native island Barbados, which gained independence from its 341-year-old identity as an English sugar colony in 1966. Like many other Caribbean islands, Barbados has long had a large, poor population of African descent; its own name means ‘bearded ones’ in Spanish and might refer to the hanging roots of trees or to the beards worn by the indigenous people encountered by the Spanish when they arrived in the fifteenth century. The island’s original name in Arawakan is “Icirougandin,” meaning red land with white teeth; today the people who live there simply call it Bim.

The people of Bim speak a ‘creolized’ English that is richly mixed with the rhythms and vocabularies of the African cultures of their ancestors. The uniquely fluid music and dance forms of the island grow out of those same traditions. Distinctive to Barbados and shaped by the embodied history of its people, the rhythms of these songs and movement patterns infuse Kamau Brathwaite’s poems. The poems themselves have been published in books whose titles— The Arrivants, Middle Passages, and Masks—retrace Afro-Caribbean histories of slavery and dislocation. Yet Brathwaite’s poems are vibrant with life and hope as they embrace the possibilities of an ever-changing world. Brathwaite himself coined the phrase “tidalectics” to describe linguistic patterns in which different idioms, sounds, voices, rhythms, and moods flow, unite, disperse, and then reunite in new configurations.

The cover of then-Edward Brathwaite’s Masks (1968), later appearing in the collection The Arrivants: A New World Trilogy (1978).

These fluid energies animate Brathwaite’s poem “Caliban,” which first appeared in his 1968 volume Masks. What is a mask? It is an assumed identity, one that often frees the person behind the mask to access and express buried parts of his or her own identity. Masks also play a vital role in African religious rituals, where they sometimes channel supernatural powers and sometimes provide protection from them. By calling his collection of poems Masks, Brathwaite tells us that he is interested in ways to tap into one’s deepest identity while also playing with alternative identities. Shielded by a mask, we are sometimes emboldened to speak the truth.

In “Caliban,’ Brathwaite puts on the ‘mask’ of Shakespeare’s Caliban so he can speak the truth of a decolonizing subject’s search for identity. Written in Caliban’s own voice, Brathwaite’s poem starts in an unidentified Caribbean city that sometimes seems to be Cuba’s capital, Havana. The city is awash in the grim debris of colonization. As colonization’s high tide has receded and European powers have departed, the island peoples have been left destitute, invisible, erased by history. Brathwaite’s poem starts out with a grim tally whose heavy weight is reinforced by repetition and a ponderous rhythm from which it seems there can be no escape: “Ninety-five per cent of my people poor /ninety five percent of my people black/ ninety-five percent of my people dead.” Caliban speaks not for himself but for “my people.” He even speaks as his people, or allows them to speak through him.

So as to make the plight of “my people” universal, Brathwaite’s Caliban next invokes the prophet Jeremiah, the biblical book of Leviticus (which is preoccupied with laws that separate the living from the dead, the pure from the corrupt), and the modern existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Caliban’s island—apparently Cuba—suffers under the weight of dead modern machines left behind on land that also seems dead, incapable of yielding the vital substances that the living need, such as cotton or bread. Echoing Shakespeare, Brathwaite’s Caliban turns to Ariel’s beautiful song of transformation from death to life (“Full fathom five thy father lies, Of his bones are coral made”). But when Caliban echoes Ariel’s song, life becomes death. Caliban’s modern island has become a world of dead ends: “out of the living stone out of the living bone/of coral, these dead/towers.” Caliban remembers political revolutions that should have brought freedom but resulted only in more oppression in the form of police abuse and even addiction to the toys of capitalism. While there is the hint of an impending storm (“the sky was cloudy, a strong breeze”), the weather only marks the Caribbean islands’ vulnerability to hurricanes, today thought to be more intense and destructive than in the past, thanks to global warming—a legacy of the European scientific enlightenment, and thus also a legacy of European colonialism. The Europeans, other words, are gone but they have left death, sorrow, and devastation in their wake. Caliban’s “people,” lifeless and impoverished, must somehow recreate themselves out of these materials.

And yet Braithwaite’s poem does not end in this world of death. Far from it! The final lines are bright with hope, and alive with new rhythms and images: “the dumb gods are raising me/up/up/up/and the music is saving me.” Caliban, who at first could only helplessly lament the plight of his people, now feels himself lifted and saved. Those early, ponderous verses sinking into blocks have dissolved and the poem stretches out long, its verse suddenly free and lithe, pulsing with life as it moves “up/up/up” along with Caliban himself.

But just how does Caliban find his way from death to life, from stasis to movement, from despair to hope? He is, to course, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Caliban, who likewise longs to break free of the chains Prospero has put on him. This modern Caliban takes Shakespeare’s own imagery and plays with it until it begins to play for him. But in order to revitalize that imagery, he infuses it with the tempos and cadences of Caribbean speech, dance, and and music. This is a poem that celebrates the sound of the human voice. The best way to appreciate that is to listen to this recording of Brathwaite reading the poem.

When you listen, you will hear the voice of the Caribbean islands, melodious, playful, its own thing. That doesn’t mean that Brathwaite’s Caliban leaves Shakespeare’s Caliban behind. The middle part of his poem is an extended riff on Caliban’s euphoric “‘Ban, Ban, Caliban; have a new master, get a new man.” This is the song Shakespeare’s Caliban sings when he believes he has found a way to break free of Prospero’s tyranny. Without escaping from Prospero’s language, Shakespeare’s Caliban plays with it, rearranging its syllables to suggest new meanings, “new” possibilities of identity and power, and even “freedom.”

But Caliban fails to break free of Prospero. By the end of the play, he is back under the magician’s thumb. That isn’t true of Brathwaite’s Caliban: he has broken the spell! But how? Is it just because he has access to other traditions and realities that belong to him and his people, not the colonial powers that have killed and erased “ninety-five percent of” them?

The key is what we might call the “middle passage” of Brathwaite’s poem—the part between its beginning and its end. I borrow this term from Brathwaite’s later volume of poems Middle Passages, where you can find his other Tempest-inspired poem, Letter Sycorax, in which Caliban steals Prospero’s laptop and uses it to reconnect with his mother’s language and “curse [Prospero] wid his own cursor.” The “middle passage” refers to the forced transportation of human beings from Africa to the Caribbean; many went to the North American colonies, and many others died in transit. Throughout his work, Brathwaite is keenly aware of the middle passage as part of the tragic history of ‘my people.’ The middle passages of his poems—the parts in the center that move us from the beginning to the end—are always important.

So what happens in the middle passage of Caliban? This is where Caliban breaks into dance, and as he “prance[s],” he begins breaking words down, experimenting with new ways of ordering them, literally creating space for himself with dashes and wide-open margins:

And

Ban

Ban

Cali-

Ban

like to play

pan

at the Car-

nival;

pran-

sing up to the lim-

bo silence

down

down

down

Here the playful, lifting cadences of island music displace the heavy, meter of the first part of the poem. The longer this Caliban sings in his native voice, the more possible it is to “ban”—get rid of—the legacies of colonial rule. Brathwaite’s Caliban liberates himself through free “play” and unbridled pleasure, through joyful experiment with what words might do spontaneously. The middle of the poem—again, the part that connects but also separates the bleak, heavy scene at the beginning from the energy of hope at the end—consists entirely of such play, thus showing how creative language can be a passport to freedom, allowing Caliban to create himself as he wishes. Hence Caliban dances as well as sings, “pran-/cing up to the lim–’/bo silence..”

But just what is the “lim–/bo silence”? Limbo in Catholic theology is the suspended state between heaven and hell. By suspending the word “limbo’ itself between two lines, Brathwaite captures this sense of suspense and makes it part of the active experience of his poem. By isolating the syllable “lim,” Brathwaite also echoes the word “limb,” evoking the part of a tree that can be turned into a stick.

The limbo itself is a dance involving a stick. You may have done the limbo yourself at a skating rink. This internationally popular game originated in the Caribbean islands. There dancers pass under a horizontal stick suspended between two vertical ones which is lowered after everyone has gone under it. Of course, not every dancer manages this; those who do not are eliminated, while those who succeed get more and more creative, often showing off their talent for contortion and fluid movement. Because of the physical skill and personal creativity involved, the limbo is a popular tourist attraction in Barbados, and even a source of income for many Caribbeans. This gives it a double meaning: the limbo celebrates versatility, flexibility, and originality. But it is also performed by acrobatic native dancers for the pleasure of American and European visitors whose money holds up the islands’ fragile economies. Here ‘s a picture of a street performance of the limbo:

Caliban imports all of these aspects of the limbo dance in his poem: “down/down/down”; “knees spread wide.” And the “limbo stick” itself appears many times in the poem, as if to transform Prospero’s magic stick—an instrument of domination—into a toy for Caliban to play and dance with. Appropriating Prospero’s stick into a new dance allows Caliban to appropriate its power for his own purposes of freedom and self-creation. As he dances, the verse form of the poem mirrors the alternation between flattening and lengthening that is part of the dance.

It would be very nice if this were all that is going on in the middle passage. But as Caliban dances the limbo, more troubling elements creep in. This is a dance for tourist consumption and as such it suggests continuing dependence on American and European money. More significant still: where did the limbo come from? As he dances, Caliban tells us;

limbo like me

long dark deck and the water surrounding me

long dark neck and the silence is over me

limbo

limbo like me

stick is the whip and the dark deck is slavery . . .

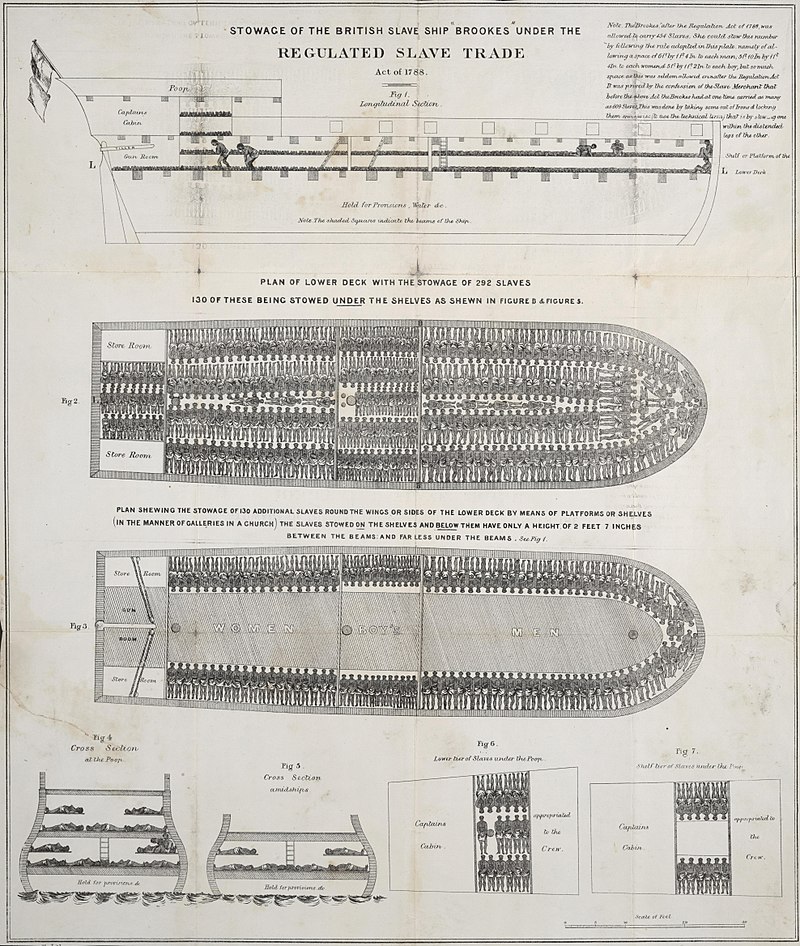

What is happening here? It turns out that the limbo is not just a popular nightclub dance. It was originally developed by African slaves who had survived the middle passage. It was even performed at wakes—rituals in which survivors sit beside the bodies of the dead. The pattern of increasing confinement mimics the often fatal experience of being crowded into the hold of a slave ship and dehumanized inside its “long dark neck.” Here is a schematic image of that crowding so you can see what it was like:

A plan of a British slave ship, showing how 454 slaves were placed on board. According to transport records, however, this same ship reportedly carried as many as 609 people. This image was published by the Plymouth Chapter of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade and is now held by the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division.

As the limbo “stick” lowers, dancers reenact that suffocating confinement. When they manage to come out of it, they celebrate the triumph of release. But each time the is stick lowered, fewer people make it under, through, and up. The limbo is thus a dance of elimination, if also of triumph for those who survive. In this way, the dance is a form of living cultural memory. In its negative side, it recreates the condition of death. In its positive side, people survive and emerge on the other side, unfold and rise in the miracle of survival. Even the spirits of those who die might be imagined to have been released by death into the freedom of an afterlife that this very ritual perpetuates. But the message is a mixed one.

By turning Shakespeare’s ship of nobles into a slave ship and Prospero’s wand into a stick he can play with and master, Caliban finds his own voice. He gives “My people” a common history and shows them how to use it to move forward. We hear “drummers” and feel the action of “dumb gods” who can still speak through the body. That is why. at the end of the poem, Caliban sings that “the music is saving me.”

The last thing we experience in the poem, is Caliban’s “hot/slow/step/on the burning ground.” He is remembering how to walk again on the shores of a foreign land. But this is also an image of hell. Destruction goes with creation. And Caliban’s steps are slow. The way forward is painful and difficult. Will he find his way? If he does, it will not only be because he transforms the dark past but because he has learned to traverse its troubling surface.

Works Cited/Referenced

Brathwaite, Edward. Masks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968. Print.

Césaire, Aimé. A Tempest. Translated by Richard Miller. New York: TCG Translations, 2002. Print.

Retamar, Roberto Fernández. Caliban and Other Essays. Translated by Edward Baker. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002. Print.

Jayne Lewis is a professor of English at UC Irvine, a faculty lecturer in the current cycle of Humanities Core, and the director of the Humanities Honors Program at UCI. Her most recent book, Air’s Appearance: Literary Atmosphere in British Fiction, 1660-1794 (Chicago, 2012) looks at how, when and where “atmosphere” emerged as a dimension of literary experience—an emergence which links the history of early fiction with those of natural philosophy and the supernatural. She is also the author of The English Fable: Aesop and Literary Culture, 1650-1740 (Cambridge, 1995), Mary Queen of Scots: Romance and Nation (Routledge, 2000), and The Trial of Mary Queen of Scots: A Documentary History (Bedford, 2000). Her present research and much of her ongoing teaching focuses on middle modern generic forms in relation to changing narratives of illness and healing, including a course on the “sick imagination” that explores illness narratives from the Book of Job through 21st-century poetry and graphic fiction. She has previously contributed to the HC Research Blog on the topic of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko.

Jayne Lewis is a professor of English at UC Irvine, a faculty lecturer in the current cycle of Humanities Core, and the director of the Humanities Honors Program at UCI. Her most recent book, Air’s Appearance: Literary Atmosphere in British Fiction, 1660-1794 (Chicago, 2012) looks at how, when and where “atmosphere” emerged as a dimension of literary experience—an emergence which links the history of early fiction with those of natural philosophy and the supernatural. She is also the author of The English Fable: Aesop and Literary Culture, 1650-1740 (Cambridge, 1995), Mary Queen of Scots: Romance and Nation (Routledge, 2000), and The Trial of Mary Queen of Scots: A Documentary History (Bedford, 2000). Her present research and much of her ongoing teaching focuses on middle modern generic forms in relation to changing narratives of illness and healing, including a course on the “sick imagination” that explores illness narratives from the Book of Job through 21st-century poetry and graphic fiction. She has previously contributed to the HC Research Blog on the topic of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko.

This is such an interesting post! I particularly liked the link to Brathwaite himself reading the poem and speaking about the symbolic resonance of the limbo. My grandparents are from Trinidad and I associated the limbo with the tourist culture in their hometown. I didn’t actually know that it had a longer history in relationship to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Thank you for sharing!