“What is my nation? Who talks of my nation?”

Shakespeare’s Henry V, Act 3, Scene 2

What separates an empire from a nation?

When I asked my students this question during our first seminar, they offered two very apt responses. First, they suggested, empires are relics of the past, and now we only talk seriously of nations. Second, if and when we do use the word “empire” today, they observed, it’s almost always negative: a label you attach to political or cultural entities that you consider corrupt or undesirable (e.g. when Ronald Reagan called the Soviet Union the “Evil Empire” during the Cold War); whereas “nation” evokes positive feelings of belonging and encourages pride in your ethnic or cultural heritage.Both observations accurately capture our contemporary attitudes and assumptions, and they reveal the great extent to which the nation-state – “an area where the cultural boundaries match up with the political boundaries” – is now regarded as the most natural and efficient form of political organization possible. But as should be apparent from our lectures in HumCore thus far, this has not always been the case. In fact, the concept of the nation-state itself did not even come into being until the 17th century, and its elevation to the preferred form of political community didn’t happen overnight but instead progressed slowly over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. So, as we transition from Professor Zissos’s lectures on the Roman Empire to Professor Steintrager’s on the European Enlightenment, it will be helpful to think about how this thing we call the nation-state came into being and how it conditioned European attitudes toward empire that would ultimately influence our own. In doing this, we will be following a scholarly method pioneered by the preeminent French philosopher Michael Foucault called genealogy, which is an attempt to discover the origins, and explain the historical evolutions, of our contemporary concepts, social behaviors, and values.

As it happens, the origin of the nation-state was a topic covered in the last cycle of Humanities Core, which centered on the theme of “War.” In that cycle, Professors Jane Newman and John Smith, both from UCI’s Department of European Languages and Studies, gave a series of lectures on the legacy of the Thirty Year’s War (1618 – 1648), a devastating conflict that ravaged central Europe (mostly in the area of present day Germany) and killed almost a third of the continent’s population before hostilities ceased. (NB: all the previous cycles of HumCore are archived on the program’s website, so you can find the materials for these lectures here if you’d like to explore the subject further.) And as Professors Newman and Smith explained, the extremity of the Thirty Year’s War arose from a number of factors.

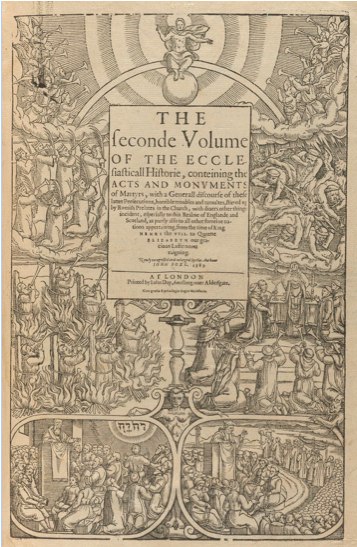

First, it was a war based on religious identity, where Protestants and Catholics both refused to recognize each other’s right to rule their own lands and assumed a kind of divine sanction for invading the other’s territories. Though both forms of Christianity, Protestants and Catholics saw each other in antagonistic and apocalyptic terms during the 16th and 17th centuries, with each defending their own doctrines as absolute truth while attacking their opponents as sinfully corrupt, almost demonic. In the context of England, which is my area of research, this extreme religious prejudice can be seen in the title page of John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments (1563), a history published under Queen Elizabeth I that chronicled Catholic persecutions of Protestants.

Starting at the bottom of the image (right), we can see how the two forms of Christian practice (Protestant on the left, Catholic on the right) are contrasted. Moving up the page, the Protestants on the left undergo holy martyrdoms celebrated by a trumpeting chorus of saints and angels. On the right, the Catholic ritual of the Eucharist is literally figured as devil worship, by its positioning beneath a cloud of jeering demons. Christ himself sits in judgement, blessing the Protestant side with his raised hand, while condemning the Catholic with a lowered one. Within the pages of the Acts itself, Foxe, like many other Protestant propagandists of the age, equated the papacy with the biblical figure of Antichrist, claiming that the Catholic Church had falsely usurped the ancient authority of the Roman empire and had used it to unlawfully tyrannize over the whole of Christian Europe. As Foxe writes in Book 1 of the 1576 edition of the Acts:

Insomuch that they [the Popes] have translated the empire, they have deposed Emperors, Kings, Princes and rulers and Senators of Rome, and set up other, or the same again at their pleasure; they have proclaimed wars and have warred themselves. And where as Emperors in ancient time have dignified them [popes] in titles, have enlarged them with donations, and they receiving their confirmation by the Emperors, have like ungrateful clients to such benefactors, afterward stamped upon their necks, have made them to hold their stirrup, some to hold the bridle of their horse, have caused them to seek their confirmation at their hand, yea have been Emperors themselves. (29, original spelling and diction modernized)

To call this an attitude leaving little room for compromise or diplomacy would be an understatement.

Second, the Thirty Years War was fought mostly by mercenary forces in the pay of various European noblemen, rather than by the kinds of well-disciplined and publicly funded armies that characterize modern nation-state militaries. As a result, soldiers were given to unrestrained rape and pillage of the civilian population, taking food and other resources that they needed to sustain their campaigns from local farms and towns. In short, it was the kind of total, chaotic war comparable to the conflicts involving Syria and ISIS happening today.

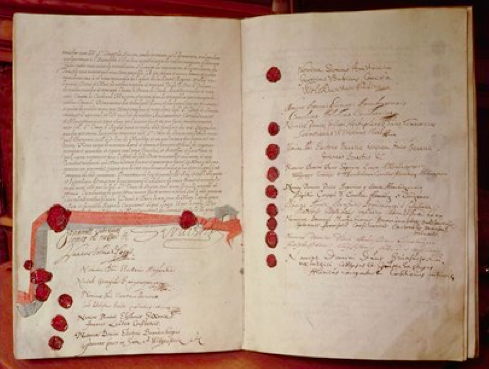

But the lasting significance of the Thirty Year’s War, as Professors Newman and Smith argued, came from how it ended. Weary of the prolonged carnage, the various sides finally came together to negotiate the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. With 109 signatories, the treaty settled a number of key issues for international relations in Europe. First, it defined (and thus ended disputes over) a number of contested borders, producing an exact map of European national territories for the first time. Second, it upheld the principle that each country had the right to abide by whatever religious identity its ruler chose, a principle encapsulated in the Latin phrase cuius regio, eius religio (“whosever realm, his religion”). Finally, it acknowledged that each nation had sovereignty over its own domestic affairs, which should not be subject to interference by any outside power. And thus, the nation-state was born: the “nation” part coming from the common identity produced by the relatively homogenous cultures and religious affiliations contained within the borders of each country; and the “state” part coming from this inchoate principle of sovereign self-determination.

The Treaty of Westphalia also signaled the weakening of religion’s hold over the political, moral, and intellectual outlook of European society – a trend that would reach full expression in the Enlightenment a century later. Take, for example, the concept of sovereignty that Westphalia established. In some ways it is similar to Roman imperium, as both denote a kind of absolute authority to command and order society it rules over, but importantly sovereignty claims neither to be universal (i.e. it applies only within the recognized borders of an individual nation) nor divinely sanctioned. Moreover, it was during the period of the Thirty Year’s War that the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes developed his influential theory of government and politics, a theory that based political authority, which Hobbes calls sovereignty, on materialist reasoning rather than religious belief.

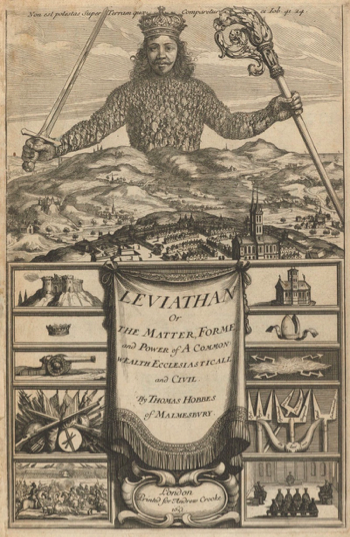

Abraham Bosse, Frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan. London (1651). Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

According to Hobbes’s account, humans form governments in order to escape the “state of nature” – a condition in which there are no laws and individuals are in a constant state of war with each other for resources and dominance. In his most important work Levithan (1651), Hobbes offers the following description of what life in this state of nature would have been like:

In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. (Book I, Chapter XIII)

Thus Hobbes argues that, In order to escape the miseries of the state of nature, individuals come together to form a “social contract,” an agreement whereby they give up their liberty to do whatever they want and place themselves under a common power (i.e. sovereign), who will keep the peace, enforce laws, and maintain order. In Leviathan’s striking title page (right), or frontispiece (which has been an endless source of scholarly interpretation itself), we can see the basic principles of Hobbes’s new philosophy rendered visually, as the sovereign’s body is allegorically composed of all the individual subjects that have legitimized his power through the social contract.

Moreover, by looking at the iconography of Hobbes’s earlier work, we can appreciate the extent to which Hobbes consciously intended for his philosophy to pry European ideas about government from the religious foundations upon which they had previously rested.

Jean Matheus, frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes, De Cive (Paris,1642). Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Consider, as evidence for this intention, the frontispiece to his work De Cive (“On the Citizen”) (left), which was published a few years before Leviathan and is where Hobbes’s most important concepts, like the state of nature and social contract, were first articulated. Note how the work’s title page includes a Christ in judgement at the very top, similar to the religious iconography that animated Foxe’s title page we saw earlier. But here a horizontal division is created in addition to the vertical one, whereby the lower half of the image offers Hobbes’s conceptual replacements for the apocalyptic dualism above. On the left, the figure of Imperium – representing government, order, and civilization – stands with sword and scales before a background of cultivated fields and industrious production. On the right, Libertas, figured as a Native American with bow and spear, represents the state of nature, before a background depicting scenes of war and competition. Thus, Hobbes visually replaces the theological categories of salvation (i.e. an eternal reward for correct religious belief and practice) and damnation (i.e. the eternal punishment for failing to believe and practice correctly) with the secular categories of civil society and the state of nature, and what he’s essentially saying to his European readers is that state authority, and each individual’s loyalty to it, should be determined by its observable ability to prevent worldly disorder, rather than its uncertain relationship to religious truth.

So, now that we’ve sketched a brief genealogy of the nation-state, how might we use it to enrich our understanding of the material that we will be encountering during Professor Steintrager’s series of lectures?

One way is to ask ourselves how the legacy of Westphalia and the Hobbesian emphasis on natural origins were taken up and re-interpreted by our assigned Enlightenment writers. For example, consider Kant’s definition of enlightenment as “the human being’s emergence from his self-incurred minority,” which is in many respects a translation Westphalian sovereignty to the level of the individual. Rousseau, on the other hand, offers a mixed set of attitudes toward the legacy of 17th century thought. He would himself take up the question of social contract, but unlike Hobbes, who considered human life in the state of nature to be wretched, Rousseau elevates nature to such an extent that he perceives greater virtue in those untouched by civilization.

Second, as we move into the topic of the British empire, it’s important to remember that it was an empire that developed after the invention of the nation-state, meaning that its organization, administration, and ideology should offer interesting distinctions from the kind of empire practiced by the Romans. What does it mean to have an empire with a nation-state at its center? Does the nation-state produce an empire that is more colonial in nature than the empires that existed before the nation-state? How did the sovereignty of the British monarchy operate differently within the borders of the United Kingdom than it did in the greater territories of the empire?

Or perhaps, even after producing our historical genealogy of the nation-state, might we still consider that nation and empire may not be that different after all?

Works Cited

Kant, Immanuel. “What is Enlightenment?” Political Writings. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991. 56-60. Print.

Robin S. Stewart received his Ph.D. in English from UC Irvine in 2013, specializing in early modern British literature and Shakespeare. In its various forms, his research focuses on how pre-modern and early modern texts can offer productive opportunities for rethinking the origins of, as well as supplying alternatives to, our contemporary cultural assumptions and values. His most recent publications are “Last Judgment to Leviathan: The Semiotics of Collective Temporality in Early Modern England” in Temporality, Genre, and Experience in the Age of Shakespeare: Forms of Time, Ed. Lauren Shohet (Arden Shakespeare, Forthcoming 2017) and “Early Modern Drama & Emerging Markets,” in Routledge Companion to Literature & Economics, Ed. Michelle Chihara & Matthew Seybold (Routledge, Forthcoming 2018). In addition to teaching in the Humanities Core Program since 2014, he teaches upper-division courses on Renaissance literature and Shakespeare, as well as writing courses in UCI’s Program for Academic English/ESL. He spent this past summer giving a talk on Chinese adaptations of Shakespeare in Hong Kong, seeing a lot of local theater, and preparing for the birth of his first child, due this December.

Robin S. Stewart received his Ph.D. in English from UC Irvine in 2013, specializing in early modern British literature and Shakespeare. In its various forms, his research focuses on how pre-modern and early modern texts can offer productive opportunities for rethinking the origins of, as well as supplying alternatives to, our contemporary cultural assumptions and values. His most recent publications are “Last Judgment to Leviathan: The Semiotics of Collective Temporality in Early Modern England” in Temporality, Genre, and Experience in the Age of Shakespeare: Forms of Time, Ed. Lauren Shohet (Arden Shakespeare, Forthcoming 2017) and “Early Modern Drama & Emerging Markets,” in Routledge Companion to Literature & Economics, Ed. Michelle Chihara & Matthew Seybold (Routledge, Forthcoming 2018). In addition to teaching in the Humanities Core Program since 2014, he teaches upper-division courses on Renaissance literature and Shakespeare, as well as writing courses in UCI’s Program for Academic English/ESL. He spent this past summer giving a talk on Chinese adaptations of Shakespeare in Hong Kong, seeing a lot of local theater, and preparing for the birth of his first child, due this December.

![Hans Ulrich Franck, Der Geharnischte Reiter [Knight in Armor] (1603-75). Etching.](https://sites.uci.edu/humcoreblog/files/2016/10/Screen-Shot-2016-10-26-at-12.36.32-PM.png)

The part that I found interesting is the portrayal of Catholicism within Christianity and Protestantism because I feel that it is still around today as Afrah has said above. Times have not changed at all it seems and the spread of different religions and sects have only opened up more judgement and hatred towards other religions and set an “us vs. them” mentality. Personally, I have had Catholic friends who are denied credibility of worshipping God and I have had one of my friend’s mothers accuse me of worshipping the devil because I was Buddhist and not Catholic like her and her daughter. On the other side, I have had my another friend’s parents test if I was Catholic or not to be judged whether I was ever allowed in their house or not. As those friend’s parents are Buddhist, they were testing to see if I was not Catholic like they are. I didn’t understand why at the time, but this blog post made it clear that it is not just prejudice against the kind of religions that we have but there are actual evidence that goes to this and voices out the reasons why people now think the way they do with artwork.

You posed an extremely interesting question at the conclusion of your blog. In terms of expansion and control, nations and empire can be considered similar. However, I do believe that that the social understanding of each word remains the same. When a person regards their civilization as a nation, it is incredibly easy to show pride and defend its decisions. If that word were to be changed to empire, people would have a tendency to see it as a controlling, overwhelming power. It is interesting how a mere word change can affect a person’s feelings, despite the fact that your blog shows they may not be so different after all.

Comparing Hobbes to Rousseau and their completely opposite interpretations of the state of nature (with the former thinking it a time of war, violence, and hatred, and the latter believing it to be a time of peace and true virtue of humanity) has always fascinated me because there are arguments to both sides. Organized religion has caused many wars and incited hatred in people for no other reason than differing beliefs, and as you analyzed here, the destructive Thirty Year’s War that killed many many people was a religious one. Organized religion is a product of civil society; a concept that Rousseau finds to be corrupting. In a sense, he is right because without such organizations, there would be no fighting over them and there might be less hatred in the world overall. ISIS and other terrorists use religion as an excuse to commit their atrocities, and they use it as a tool to bring people in as well. However, Hobbes can also be argued for, as without any semblance of law, anarchy would reign supreme and martial law would be permanent, spreading destruction just as long as violent people exist (forever).

In response to your final question of empire and nation, I believe that there is hardly a difference between the two. The connotation of nation is a more positive one, with people announcing their nationality and recounting their family history with pride, happy to be a part of multiple cultures and to create an identity around those cultures. Empire, on the other hand, is more negative, with greed, oppression, and an obsession with “progress” and expansion being major defining traits. The truth is that many empires can do a lot of good, and nations can be directed by more negative desires and emotions. Both have people grouped together under an identity which can be shaped by the actions of their empire/nation and its leaders. Overall, it’s important to remember individuality and that determining who you are and who you want to be should be by your own standards, and not wholly by where you hail from.

I find it exceptionally interesting that the idea of a nation-state is a, relative to the history of civilization, new concept, as it emphasizes the many different ways humanity has seen the world as well as the many different ways of thinking they stressed. The idea of identity has evolved so much throughout the years, from being a part of an empire, to ethnological and ideological identities being the predominant distinguishing feature amongst peoples. Especially interesting is the usage of identity as a basis for violence and warfare, an issue that will seemingly persist throughout humanity’s existence. All in all a good and informative answer to the question.

I think the interesting idea is the connection to modern terrorist regimes, such as ISIS. But, it is not necessarily the idea that ISIS is evil, it’s the idea that any interpretation of a specific religion can cause such destruction. Many people believe that Muslims and the Islamic religion are evil due to the terrorism that has ensued from several groups’ radical interpretation of the Qur’an. What they fail to realize is that the religion is not responsible, but the individual’s interpretation of the religion. The Thirty Years War was a result of religious control. It is not just Islam that can breed violence. People fail to realize that these religious empires of destruction can arise from any religion, not just Islam.

I really love your interpretation of Hobbes’ ideals and his connections to the occurrences and outcome of the Thirty Years War, in which religion’s influence over the political state had began to weaken. It appears as if the Treaty of Westphalia had been the initial catalysis for this movement, in which Hobbes’ ideals simply influenced and further enhanced this straying from religious reasoning for the basis of political authority. I find it interesting how even in today’s time and government, the separation of church and state now exists due to Hobbes’ theoretical ideas of government and politics. However, our nation is “under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” And so, is the gap between church and state still truly defined? And if it is not, does this ambiguous definition define America as a nation-state, therefore implying that an empire what truly relies on materialist reasoning?

One thing I find interesting is the discrimination against Catholic people within the Christian community that is seen even today also possibly being reflected in this post. Although I myself am not Christian, I have had Catholic friends who have told me about their experiences of people even denying them the label of “Christian”, which I think reflects in this post from the explanation of Catholic practices being seen as demon worship. I also found that the analysis of images in this essay helped greatly in explaining the historical context for what was happening, as it not only provided a visual example, but also provided more proof by showing physical manifestations of people’s feelings towards this subject at the time.

It is amazing how much influence the Treaty of Westphalia had on the world in the 17th and 18th century. It defined the rights for states to exist, and gave them their own borders and the right to organize their own laws and religion within a territory. The treaty also began a kind of separation between religion and government. To me, this separation is what allowed the enlightenment to flourish in Europe. Hobbes was able to create his theory on political authority because of this separation, and his theory still has standing today because of the belief that people gave the state power not divine authority.

The concept of cultures learning to come together because of a costly conflict is a very interesting one. I had not previously considered that the concept of the nation-state would be a 17th century conflict; I would have believed anyone who told me that it had existed as long as there was any entity of government. The concept of the nation-state seems to have greatly impacted the enlightenment philosophers. As you wrote, it became the basis for many of their ideas. I would like to add that many modern fields, such as International Relations, also seem to use the concepts established by treaty of Westphalia as a way to define the modern state.

I really like the image analysis you did on the picture pulled out of John Foxe’s, Acts and Monuments. Really giving great detail onto what is occurring on the image itself, and honestly, it really fascinated me. The fact that Jesus is blessing the Protestant side by having his hand towards them and like you said, “condemning” the Catholic side with a lowered arms towards their side, clarified to me why he was in such a particular position. It’s kind of interesting too how Jesus is also positioned as the Sabbatic Goat which is the representation of Baphomet.

Wow! In all consideration, this idea between empire and nation has been one that I have been contemplating for quite some time now. And yes, I agree completely. In response to your last question in your blog, I would say that it is all dependent on who, what, where, and why an individual views a particular setting as an empire or a nation. One being that since being a part of an “empire”, there is a tendency for most to not recognize our own “empirical behavior” – the acknowledgement of these behaviors will become obvious once we step into another country. I guess the ambiguous and difficult configuration of an answer for this specific discussion is whether or not should we change it? If anything, is it the betterment for ourselves? Or for others?