The following is a revised version of a talk given as part of a “Shakespeare on Film” panel at the 2013 Popular Culture Association/ American Culture Association National Conference in Washington, D.C., and, like Writing Assignment 4 for this cycle of Humcore, it performs a comparative analysis on an example of Shakespearean appropriation, identifying how certain themes originally appeared in Shakespeare’s plays and then reflecting on how these themes have changed in the process of adaptation. For students currently writing and revising their own essay drafts, it offers a model of how to a) select and incorporate relevant passages from Shakespeare, b) use secondary sources to develop a central argument, and c) describe and analyze film as a medium. While this post does not rely heavily on the technical vocabulary of film analysis (a good introduction to which can be found here), it does include detailed descriptions of the various scenes and cinematic elements being analyzed. Students may compare these descriptions with the actual excerpts of the film provided throughout to get a sense of how to translate the medium of cinema into written form.

The following is a revised version of a talk given as part of a “Shakespeare on Film” panel at the 2013 Popular Culture Association/ American Culture Association National Conference in Washington, D.C., and, like Writing Assignment 4 for this cycle of Humcore, it performs a comparative analysis on an example of Shakespearean appropriation, identifying how certain themes originally appeared in Shakespeare’s plays and then reflecting on how these themes have changed in the process of adaptation. For students currently writing and revising their own essay drafts, it offers a model of how to a) select and incorporate relevant passages from Shakespeare, b) use secondary sources to develop a central argument, and c) describe and analyze film as a medium. While this post does not rely heavily on the technical vocabulary of film analysis (a good introduction to which can be found here), it does include detailed descriptions of the various scenes and cinematic elements being analyzed. Students may compare these descriptions with the actual excerpts of the film provided throughout to get a sense of how to translate the medium of cinema into written form.

Dramatizing the historical events surrounding George VI’s ascension to the English throne in 1936 after his brother Edward VIII famously abdicated to be with “the woman I love,” The King’s Speech eschews the more typical Hollywood melodrama of Edward’s romantic scandal and instead follows George VI (“Bertie”), played by Colin Firth, during his personal battle to overcome a debilitating stammer and become the inspirational spokesman for a nation on the brink of war. The film is part of a new wave of historical cinema that has revived the most salient elements of the Shakespearean history play, particularly the genre’s fascination with crises of sovereignty and the role of individual personality in the ineffable tide of historical change. But unlike the epic costume dramas of the 1960s, such as Becket (1964), A Man for All Seasons (1966), or Anne of a Thousand Days (1969), these recent films are set within the pointedly modern contexts of mass media, celebrity culture, and global politics. Other examples of this cinematic trend include Peter Morgan’s films The Deal (2003), The Queen (2006), and The Special Relationship (2010), which explore the recent history of Britain through the career of Tony Blair, while the HBO films of Danny Strong – Recount (2008) and Game Change (2012) – apply the genre to contemporary American politics.

The King’s Speech, however, is the film that most consciously and explicitly engages with its Shakespearean influence, embodied in the character of George VI’s Australian speech therapist Lionel Logue, played by Geoffrey Rush. Screenwriter David Seidler cleverly exploits the biographical fact that Logue was an amateur Shakespearean actor to weave the Bard’s words and themes throughout the film. In fact, Logue’s very first appearance on screen is attended with a Shakespearean quote. In this scene, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, played by Helena Bonham Carter, having come to Logue’s office to enlist his services for her husband, discovers a rather drab and dilapidated space. Emerging from the bathroom with the sound of a flushing toilet receding into the background, Logue, aware of the impression his home can make, quips, “Poor and content is rich and rich enough” – a line from Othello. When Elizabeth responds with a bemused, “I’m sorry,” Logue promptly interjects, “Shakespeare. How are you?” and thrusts out his hand in a remarkable gesture that fuses citation and introduction – as if he were claiming to be the Immortal Bard himself.

Logue’s practice of speaking with a Shakespearean cadence reflects, at one level, his status as a product of empire. As an Australian transplanted to London, Logue is an outsider in love with an English cultural tradition that actual English men and women seem all too ready to deny him. To drive this marginalization home, the film presents a brief interlude where Logue auditions for an amateur Shakespeare troupe from Putney, the leader of which barely lets Logue get out the lines to Richard III’s opening soliloquy before cutting him off with a derisive, “I didn’t realize that Richard III was king of the colonies.”

But the allusion to Richard III in this scene serves as something more than just an opportunity to illustrate Logue’s experience of cultural rejection. Instead, I want to suggest that it represents Seidler’s winking acknowledgement of the film’s conscious appropriation, and often inversion, of a host of Shakespearean themes and tropes.

In fact, the overall arc of the film’s action is an ironic reversal of the plot to Richard III. In Shakespeare’s play, Richard III is presented as a man who, because he possesses a defect that keeps him from enjoying a private life, pursues instead a path of public ambition through cunning and strategizing. As the hunchback Richard tells the audience in his opening monologue, “since I cannot prove a lover / To entertain these fair well-spoken days, / I am determined to prove a villain / And hate the idle pleasures of these days” (1.1.28-31). In the King’s Speech, however, Bertie’s “defect” frustrates the demands and expectations of his public position, and where Shakespeare’s murderous “Machieval” claws his way to the crown by sheer force of will, Bertie practically has to be dragged there kicking and screaming. When Bertie’s wife tells Logue that her husband has to speak publicly and can’t switch jobs, Logue jokes, “indentured servitude?” She replies, half-grinning, “Something of that nature, yes.”

Indeed, this sentiment of being overwhelmed by public duty and desiring the life of a private man is a common theme in Shakespeare’s histories. In Henry V, a play about one of England’s most celebrated medieval kings, the eponymous ruler delivers the following melancholy reflection, just before the fateful battle of Agincourt:

O hard condition,

Twin-born with greatness, subject to the breath

Of every fool, whose sense no more can feel

But his own wringing! What infinite heart’s-ease

Must kings neglect, that private men enjoy!

And what have kings, that private men have not too,

Save ceremony, save general ceremony?

And what art thou, that suffer’st more

Of mortal griefs than do thy worshippers? (Henry V, 4.1.233-42)

This “twin-born” nature of English monarchs – one of Shakespeare’s favorite history play tropes – was famously identified by the medieval historian Ernst Kantorowicz as the doctrine of “The King’s Two Bodies” – the first, a mortal, natural body that is the seat of the private individual, and the second, a political, deathless body that is the abstract embodiment of the English nation continuing in perpetuity.[1] According to Kantorowicz the concept of the “two bodies” developed in legal discourses of 16th century as a necessary bridge between the mystical, theological concepts of the medieval imagination and the modern secular notions of the state. In a seminal reading of Shakespeare’s Richard II, Kantorowicz asserts that “the legal concept of the King’s two bodies cannot…be separated from Shakespeare” because it was Shakespeare who “eternalized the metaphor” in a way that continues to shape the cultural imagination of Western civilization.[2]

As a modern historical drama about a modern sovereign, The King’s Speech certainly plays upon Shakespeare’s eternalized metaphor, but it does so with a keen awareness that the metaphor has undergone a fundamental re-imagination since the 16th century. Indeed, the modern conception of the English monarchy, starting with the Glorious Revolution of 1688, has been marked by a concerted effort to suppress the importance of the King’s natural body and to completely divorce the private will of the sovereign from the functioning of public authority.[3] “If I’m a king, where’s my power?” Bertie exclaims in the penultimate scene of the film, acknowledging this limited and circumscribed role the monarch now inhabits: “Can I form a government? Can I levy a tax? Declare a war? No.” But the mystical element that still peeps through, the one that almost embarrassingly attests to the fact that the king is still the clumsy persona mixta of a pre-modern constitutional tradition, is the importance of the voice. “And yet I’m the seat of all authority” Bertie continues, “Why? Because the nation believes that when I speak I speak for them.”

While acknowledging the dull reality of 20th century kingship, The King’s Speech nevertheless takes seriously this mystical kernel still alive and active in the operation of sovereignty. For even in the modern age, it is the sovereign’s voice that the nation is supposed to respond to, particularly in times of crisis, and this voice therefore continues to function as the symbol of a stable and secure order. But the film is not merely fascinated with the mystical authority of the king’s voice in the abstract; its interest also lies in the unique historical moment of the early 20th century, when the development of broadcast technology raised the stakes of the sovereign’s personality in new, and potentially disruptive, ways. “In the past, all a king had to do was look respectable in uniform and not fall off his horse,” George V, played by Michael Gambon, grumbles to his son Bertie, “Now, we must invade people’s homes and ingratiate ourselves with them. This family’s been reduced to those lowest, basest of all creatures. We’ve become actors.”

Extending and ironizing this analogy between royal authority and public performance, the visual vocabulary of the film draws remarkable parallels between the traditional iconographies of royalty and the material technology through which that royalty will be translated in the age of mass media. Thus, the very first images of the film are a series of lingering shots upon a single microphone, impressive in its bulk and resembling a kind of missile, as if to suggest that one false move will unleash its powerful, destructive force. This, as the film’s framing implies, is the new throne, the new crown.

We are then shown the pre-broadcast ritual of a nameless BBC announcer, wherein the film offers a kind of visual parody of a coronation ceremony, inviting the audience to witness the anointing and blessing of the voice before it takes its place in this new seat of power.

The fact that it is a nameless BBC announcer undergoing this parodic coronation emphasizes the profound effect that this new technology will have upon the nature of power and authority. Later in the film, when Bertie and his family have finished watching a newsreel of his own coronation, the images and sounds that immediately follow are of Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies. Bertie sits silently watching Hitler’s bombastic performance as a young Princess Elizabeth asks, “Papa, what’s he saying?” “I don’t know,” Bertie wryly replies, “but he seems to be saying it rather well.”

As the film suggests, for a consummate speaker like Hitler, the technology of the microphone magnifies his personality, and it is in this act of technological magnification, rather than the force of custom or tradition, that the authority of modern authoritarianism is created. Bertie, by contrast, with an authority based on a tradition much bigger than his individual self – the thousand year legacy of British royalty – finds himself dwarfed and overwhelmed by the prospect of personal magnification, a theme that the film’s director Tom Hooper signals brilliantly through camera angles and shot composition, wherein microphones are continually eclipsing and obscuring Bertie’s face.

Bertie’s stutter thus operates as a kind of return of the repressed, embarrassingly foregrounding the continued fact of the king’s physical presence, his natural body. The plot of the film, therefore, principally revolves around achieving some kind of harmonious re-alignment of the two bodies paradox.

Enter: Lionel Logue with his Shakespearean eloquence and radical approach to speech therapy. And while Bertie’s rise to the throne is a reversal of Shakespeare’s Richard III, his friendship with Logue recalls and inverts many of the tropes contained in the Prince Hal/ Falstaff relationship of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Parts 1 & 2.

Simon Russell Beale (left) as Falstaff and Tom Hiddleston (right) as Prince Hal in PBS’s The Hollow Crown (2012)

Like Bertie, Prince Hal, in Henry IV, Part 1, condescends to a state of familiarity and equality in order to learn how to “speak” the language of his subjects, proclaiming while in the riotous company of Eastcheap, “I can drink with any tinker in his own language during my life” (2.4.18-20), a skill that will later serve him well when he must rally his troops before the battle of Agincourt – a feat he achieves through his famous St. Crispin’s Day speech, calling upon his “Band of brothers” to shed their blood with him (Henry V, 4.3.18-67).

Hal’s Rejection of Falstaff Upon Becoming King Henry V (from an 1830 Edition of Shakespeare’s Plays edited by Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke)

However, Hal must ultimately renounce Falstaff and the friendship that taught him this speech because of the threat that such a private friendship poses for the public good. Shakespeare famously illustrates this threat in Falstaff’s reaction to hearing of Hal’s ascension to the throne, where the reprobate knight proclaims, “the laws of England are at my commandment” (2 Henry IV, 5.3.136-7), a sentiment which exemplifies the common Renaissance fear that corrupt personal advisors might turn the king’s power into a tool for private gain.

The filmmakers seem very cognizant of the threat Logue represents within the confines of these older tropes, and interestingly, there are many sinister associations with Logue’s character subtly sprinkled throughout the film. Consider for instance the visual sequence of Elizabeth’s initial visit to engage Logue’s services for her husband. First, we see her in a chauffeured car on her way to the office, but because of the thickness of the fog, a man walks out in front as a guide. Then, upon arriving, she must cage herself in a rather menacing-looking elevator and wait for its slow decent to a lower floor. Though very slight visual cues, the fog and the elevator give the unsettling impression of entering a kind of Grecian underworld. The man guiding the Duchess’s car through the fog in particular conjures up images of Charon leading a freshly arrived soul across the river Styx.

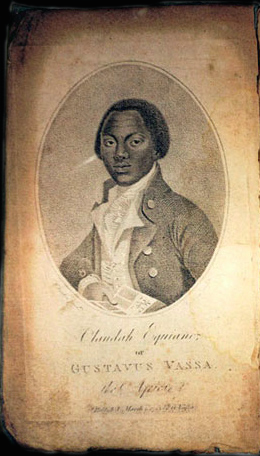

Then we have Logue’s Shakespearean quotes themselves, all of which come from very sinister contexts. Besides Richard III, the “poor and content” line is spoken by Iago and is delivered during the very scene where he first plants the doubt about Desdemona’s virtue in Othello’s mind, a doubt that will eventually ripen into the murderous jealousy that causes Othello’s tragic downfall. Logue’s third instance of Shakespearean quotation comes in the form of Caliban’s famous “Be not afeared” speech describing the The Tempest’s enchanted Isle (3.2.135-43), a speech which Logue delivers, with an impromptu hunchback, for the entertainment of his sons.

While the lyricism of the speech is breathtaking, it’s important to remember that, in its original context, Caliban is trying to convince the newly shipwrecked commoners Trinculo and Stephano to kill Prospero for him – an instance of the colonized subject attempting to destroy the man who holds sovereign sway over him.

Russell Brand as Trinculo (left), Alfred Molina as Stephano (center), and Djimon Hounsou as Caliban (right) in Julie Taymor’s The Tempest (2010)

Granted, the film never depicts Logue as harboring violent intentions toward Bertie, but it does position him as a subversive figure. The suspicion of Archbishop Cosmo Gordon Lang, played by Derek Jacobi, towards Logue, particularly in the run up to Bertie’s coronation, is construed by the film as mostly being motivated by class snobbery. However, the suspicion also arises from the aforementioned fear that personal advisors and favorites to the king can become threats to the constitutional order. Here we may again recall Falstaff’s hopes in Hal’s succession or the figure of Piers Gaveston as depicted in Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II. Visually, the film registers this age-old suspicion of favorites in its shot composition and its staging. Consider, for example, the camera angle during Bertie and Logue’s conversation, prior to Edward’s abdication, about whether or not Bertie has the potential to be king. As if showing us Bertie’s own internal interpretation of how taboo such a consideration is, the film frames Logue as a kind of devil on Bertie’s shoulder, whispering treasonous temptations into his ear.

Or consider the image that we get during the rehearsal for Bertie’s coronation. Having dismissed everyone but Logue, Bertie falls into a fit of despair, asserting that he has only come to this point because of Logue’s ambition to have a star pupil in the future king. Getting up from the throne and looking off into the distance, Bertie morbidly imagines that his legacy will be that of “Mad King George the Stammerer, who let his people down so badly in their hour of need that…” Bertie does not complete the self-pitying prediction because as he turns, he sees Logue casually lounging in Saint Edward’s chair, as naturally as if he were king himself.

Finally, during the climactic wartime broadcast where Bertie announces Britain’s entry into World War II, the crucial moment towards which all of Bertie’s speech therapy (and thus the film as a whole) has been building, we are given the visual of Logue actually conducting Bertie as if he were some kind of orchestra (see edited clip below). However, the film only raises these symbolic fears of usurpation in order to demonstrate that they are unfounded. Logue’s sitting in Saint Edward’s chair merely serves to demonstrate that Bertie does not need to be intimidated by the materials of ceremony. (Here, Bertie’s self-affirming shout of “I have a voice!” is essentially the film’s feel-good climax). And well before the conclusion of the wartime broadcast, Logue has stopped conducting and stands transfixed, listening to his King’s voice as merely one subject among many. In this climactic moment, we, as an audience, are meant to see how much Logue has helped Bertie discover his own voice and become his own man, registered in the shot composition by a suspended microphone that now reflects Bertie’s face rather than obscuring it.

By inverting the old Shakespearean tropes, the film validates and indeed celebrates the king’s personal friendships as an essential means to fulfilling his royal duties – a touching twist for any Shakespearean critic who thought Hal’s rejection of Falstaff was an unkindness too difficult to stomach. In fact, Logue’s insistence upon intimacy while treating Bertie, and his psychological approaches to speech therapy (an historical inaccuracy on the part of the filmmakers), remind us that the King’s Speech not only updates its Shakespearean themes according to modern media, but also updates the problem of the King’s two bodies, and the king’s voice, in the context of post-Freudian psychology. As the Lacanian critic Mladen Dolar has written in his work, A Voice and Nothing More, “we are social beings by the voice and through the voice; it seems that the voice stands at the axis of our social bonds, and that voices are the very texture of the social, as well as the intimate kernel of subjectivity.”[4] Indeed, the film presents Bertie’s stuttering as originating in the formation of this “intimate kernel of subjectivity” and further exacerbated by the process through which it gets integrated into a larger social fabric. Significantly, Logue is able to convince Bertie to start therapy through a trick. In what has become the film’s iconic scene, Logue asks Bertie to read Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy while listening to classical music blasting through a set of headphones. Logue records Bertie’s performance on a record, which Bertie refuses to listen to until much later. When he finally does, however, hearing his voice reciting Shakespeare’s most famous speech without hesitation or mistake, he immediately begins treatment. This trick works, the film implies, for two reasons. First, it allows Bertie to efface himself, to not be crushingly self-conscious of his own voice while he is speaking. Second, the recording allows him to experience his own voice from the perspective of another, to be alienated enough from it to see it as an object in itself.

As the film suggests, at a deep psychological level Bertie lacks confidence in the world of social response that his voice is supposed to elicit. Here we might recall how, according to Kantorowicz’s concept of the King’s Two Bodies, the peripeteia of Shakespeare’s Richard II occurs when the besieged monarch loses confidence in the mystical power of his kingly capacity and at last becomes aware of his own limited creaturely existence: “I live with bread like you, feel want, / Taste grief, need friends: subjected thus, / How can you say to me, I am a king?” (3.2.175-7). In Bertie’s case, however, the loss of faith is much more profound, for we learn that as a child he was subject to abuse by a nanny who wouldn’t feed him, and that it took his parents three years to notice. The scene in which this information is revealed becomes all the more poignant by the incorporation of one of Logue’s speech therapy techniques introduced earlier in the film. In that earlier scene, Logue explains to Bertie that singing his words using a familiar melody can help keep him from stuttering, at which suggestion Bertie tries the melody to “Swanee River.” So when Bertie later begins to talk about his childhood and the stress of his memories increases the severity of his stammering, Logue advises him to sing it, which results in Bertie confessing the awful neglect of his nanny – “then she wouldn’t feed me” – while finishing with the original lyrics to “Swanne River” – “far, far away.” It’s a brilliant bit of staging on the part of the filmmakers, as it serves to underscore how this traumatic experience instilled feelings of isolation and distance in Bertie, and ultimately caused him to lose faith in the power of his own voice to bridge that distance.

A big part of Logue’s therapy throughout the film, then, is to create a smaller version of this world of social response, a more intimate realm somewhere between the purely public and purely private, where Bertie only needs to worry about a single recipient and can be confident that this recipient is a friend. This theme is most directly illustrated in the final scene where Bertie delivers his inspiring wartime broadcast in a small room just to the side of the palace offices. Only Logue is there, instructing Bertie to “Say it to me, as a friend.” Coupling the intimate space of self-with-other with a palpable demonstration of mass media’s potential for self-amplification, the scene finally banishes the specter of totalitarianism and tyranny heretofore haunting the film’s meditation on modernity and sovereignty, opting instead for the emotionally satisfying resolution of melodrama, albeit (it must be admitted in this context) melodrama of the highest order.[5]

But it behooves us as attentive viewers to recognize the quaint nostalgia at the heart of this melodramatic resolution – a nostalgia which readily acknowledges the first half of the 20th century as a time of political and social upheaval, but nevertheless takes comfort in the assurance of a worthy future ahead. How else are we to understand the bizarre incongruity of the film’s final moments, where a declaration of war is greeted not with sadness or trepidation, but with relief and triumph, as family members and palace officials cheerfully applaud Bertie like a sports movie underdog who’s just won the big game?

By contrast, at the dawn of 21st century, though we feel a commensurate sense of social and technological upheaval, what we lack is that easy faith in the brighter tomorrow, the confidence that the bitter struggle ahead will inevitably lead to some grand, ennobling victory. We shouldn’t forget that, even though it won Best Picture in 2010, The King’s Speech wasn’t the only historical drama on that year’s list of Oscar contenders. David Fincher and Aaron Sorkin’s The Social Network garnered as much, if not more, critical and popular acclaim as the King’s Speech, but the tone and guiding metaphor of each film could not be further apart.

Even the title, The Social Network, evokes a de-centered, depersonalized world of distributed power and murky social obligations, while the film itself structurally refuses to empathize with or reject its central protagonist through the frame story of a legal deposition, leaving it unclear whose version of events is the truth. Through the course of the film, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, played by Jesse Eisenberg, is portrayed as a social maladroit, whose rise to the top is fueled by a combination of unimpeachable talent, unshakable resentment for the existing social hierarchy, and just a dash of Machiavellian ruthlessness – in other words, like a Richard III. Clearly, the more unsettling strains of Shakespeare’s tragic vision have not been rendered obsolete by the modern age, but indeed continue to resonate with contemporary doubts and anxieties about where our society might be headed.

We must ask ourselves, therefore, what it says about our own historical moment that, when it came time to choose between these two films, popular imagination and institutional recognition in America longingly bent toward the comforting paradigm of the past, indulging an atavistic impulse to listen to and follow the steady, singular voice of a sovereign.

Notes

[1] I must acknowledge Robin Wagner-Pacifilci’s post on the blog Deliberately Considered as the first public identification and discussion of this aspect of the film. 1/10/11. < http://www.deliberatelyconsidered.com/2011/01/the-king%E2%80%99s-speech-the-president%E2%80%99s-speech/>

[2] Ernst Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 26.

[3] The classic analysis of the sovereign’s circumscribed and symbolic role in England’s post-1688 constitutional government is Walter Bagehot’s The English Constitution (1867).

[4] Mladen Dolar, A Voice and Nothing More (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006), 23.

[5] For an analysis of the relationship between sovereignty and friendship in Renaissance literature, see Laurie Shannon, Sovereign Amity: Figures of Friendship in Shakespearean Contexts (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002).

Robin S. Stewart received his Ph.D. in English from UC Irvine in 2013, specializing in early modern British literature and Shakespeare. He has written previously for the Humanities Core Research Blog on Empire and the Nation-State Before the 18th Century. For interested students, he will be teaching a course on Shakespeare (E103) during the upcoming Summer Session that will be coordinated with the New Swan Theater’s productions of The Tempest and Taming of the Shrew. Students who enroll in the course will read three plays (The Tempest, Taming of the Shrew, and King Lear), analyze various film versions of each, and, as their final assignment, write their own creative adaptation of a chosen Shakespeare scene.

Robin S. Stewart received his Ph.D. in English from UC Irvine in 2013, specializing in early modern British literature and Shakespeare. He has written previously for the Humanities Core Research Blog on Empire and the Nation-State Before the 18th Century. For interested students, he will be teaching a course on Shakespeare (E103) during the upcoming Summer Session that will be coordinated with the New Swan Theater’s productions of The Tempest and Taming of the Shrew. Students who enroll in the course will read three plays (The Tempest, Taming of the Shrew, and King Lear), analyze various film versions of each, and, as their final assignment, write their own creative adaptation of a chosen Shakespeare scene.