“The beautiful and the constant Imoinda” (77). These are the last words of Aphra Behn’s 1688 novella Oroonoko; or, the Royal Slave, a work justly celebrated for its exploration of race and power through the figure of Behn’s titular protagonist, the “royal slave” Oroonoko. It is Oroonoko’s story that captures our attention and arouses our admiration, frustration, and horror, and it is Oroonoko who gives the book its title. Yet in a narrative that foregrounds issues of names and naming, Behn’s female narrator ends not with Oroonoko’s name but that of his wife and lover. And, as is not the case with Oroonoko, the narrator expresses no ambivalence toward her. Indeed, while the second half of the novella refers to Oroonoko by the name his European purchasers impose on him—Caesar—Imoinda’s original name is restored to her in Behn’s final sentence.

Why all of this should be is a question worth asking, for it tells us that Imoinda is as important as Oroonoko to Behn’s analysis of power in a ruthless colonial world where heroic ideals of beauty, constancy, and honor are under siege. Literary historians know that Behn published a number of romances like Oroonoko in the last years of her life, and that they tended to spotlight female protagonists, who usually appear in their titles: The Fair Jilt, The History of the Nun; The Adventure of the Black Lady; The Unfortunate Bride. If Oroonoko had been titled Imoinda, what kind of story would it have been? Would we like Oroonoko himself less or more? And in relegating Imoinda to the edges of the story we have, is Behn perhaps drawing our attention to the ways women are invisible or marginalized in all of the cultures she explores in her tale? Who is Imoinda and why and how does she matter?

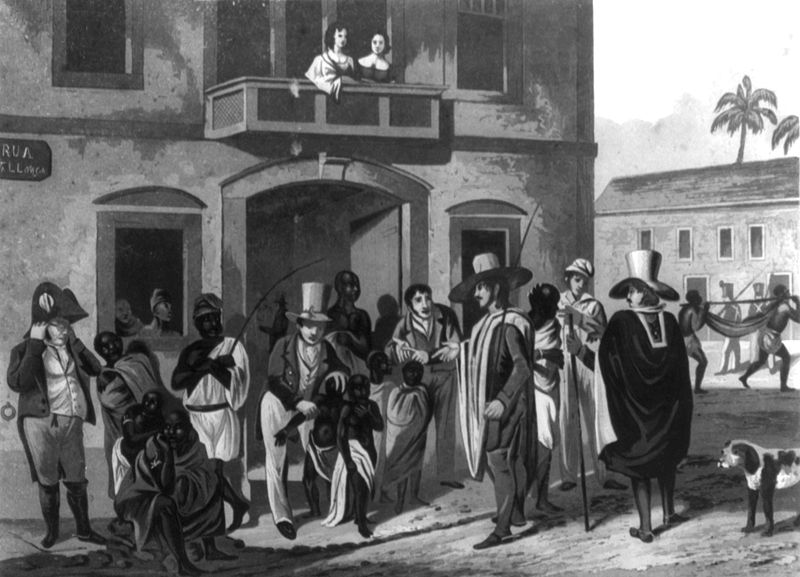

In an important essay also cited in Vivian Folkenflik’s blog post on Oroonoko’s market scene, the literary critic Laura Brown observes that Behn’s “narrative must have women, and it generates […] female figures at every turn, as observers, beneficiaries, and consumers of Oroonoko’s romantic action” (235). Brown is referring partly to Behn’s female authorship and female readership at the time of the book’s original publication. But she also reminds us that Behn is interested in Oroonoko’s relationship to women—a relationship that is presented as a key component of his virtue and identity as a romantic hero. His undying ardor for Imoinda in the decadent court of Coramantien is one of the things that elevates him: he was, claims the narrator, “as capable of love as it was possible for a brave and gallant man to be; … for sure, great souls are most capable of that passion” (16). Behn’s female narrator wryly leaves it an open question as to how “capable” of love Oroonko might actually be, but Imoinda is first introduced in the context of his “passion” for her. This is treated as a source of equality and ultimately as the source of Oroonoko’s subjection to her: “To describe her truly, one need say only, she was female to the noble male the beautiful black Venus to our young Mars, as charming in her person as he, and of delicate virtues. I have seen an hundred white men sighing after her and making a thousand vows at her feet…and she was, indeed, too great for any but a prince of her own nation to adore” (16). Sure enough, the instant Oronooko sees Imoinda, she “gained a perfect conquest over his fierce heart” (17). The narrator stresses Imonda’s power over the warrior Oroonoko while also stressing the purity of their love in a “country, where men take to themselves as many as they can maintain” (17).

But if Imoinda is at first presented as powerful, her reality in a world where “men take [women] to themselves” is somewhat different. Oronooko himself “vows that she should be the only woman he would possess” and seems to regard her as his property at the same time that he idealizes her and acknowledges her sway over his heart. More to the point, their love story unfolds in the decadent court of Coramentien, bound by customs that privilege male sexual authority. Thus Oroonko’s hundred-plus-year-old grandfather, the king, identifies the “maid” Imoinda as the perfect woman to serve his own sexual desires in the “sort of seraglio” he maintains (21). The king is obsessed with Imoinda’s physical virginity, as is Oronooko, and equally obsessed with being the sole possessor of this “treasure” (21). Imoinda is valued as property belonging to men and despite the ways Behn’s imagery makes her Oroonoko’s equal, she—unlike him—has no real control over her body. She is forced to grant the old king unspecified sexual favors and all of the conflict that erupts at court is over the question of which man has the right to own her. As Brown puts it, “the desirable woman serves invariably as the motive and ultimate prize for male adventures” (334).

The critic Charlotte Sussman is even more pointed: “Imoinda is a possession even before she is a slave,” Sussman writes, and her “exile in Surinam […] is not so much a transition from freedom to slavery as a transition from one code of property relations to another” (247). At issue here is the “transition” itself. It contrasts with Oroonko’s transition into captivity: where he is tricked by a slave trader and is in that way complicit in his own domination, Imoinda is passively sold by the king. She has no choice about the fate of her body—a state that persists in the New World. Here her owner, Trefry, is tempted to rape her and her pregnancy prompts Oroonoko (now Caesar) to revolt against European colonial rule because her child (which he regards as his) will belong to her owners, not to her. Hence, though Imoinda and Oroonoko are equally matched in many ways—Venus to Mars, elite courtier to elite courtier—Behn reminds us again and again that Imoinda’s body has never belonged to her. While most of our attention is drawn to the domination of one religious and ethnic group by another, Behn also suggest that, the world over, one gender is programmatically dominated by the other.

Most feminist criticism, like that of Brown and Sussman, focuses on the ways Imoinda is depicted as a “possession” rather than a person. Clemene, the name she is given in the so-called New World, seems to claim her as the property of those who rename her, and when Oroonoko slits her throat not long before his own death, he not only characterizes her as “the price” he has paid for his own “glory,” but buries her only up to the neck so that “only her face he left yet bare to look on,” as if to claim her as an art object that belongs to him (72). At the same time, however, we are told that once Oroonoko had done so, ”he had not power to stir from the sight of this dear object” and we also learn that she herself wanted to die: “He found the heroic wife faster pleading for death than he was to propose it” (71). It is also Imoinda who urges Oroonoko to revolt. Once she “began to show she was with child, [she] did nothing but sigh and weep for the captivity of her lord, herself, and the infant yet unborn” (61). And during the rebellion itself, Imoinda fights heroically beside her husband on a continent whose major river, the Amazon, is named after the legendary women warriors of the Greco-Roman past: “Imoinda who, grown big as she was, did nevertheless press near her lord, having a bow and quiver full of poisoned arrows, which she managed with such dexterity that she wounded several and shot the governor in the shoulder” (65). (Tellingly, it is another woman—“an Indian woman, his mistress”—who has the power to heal the governor by sucking the venom from his wound.)

Behn’s Imoinda can thus express her power and heroism only in limited, oblique ways. She is constrained by the realities of cultures that privilege men whether they are in Surinam or in Coramantien, or indeed in England, where Behn’s implied (female) reader resides. But, as Sussman observes, within these constraints, Imoinda finds ways to “take [her] biology into [her] own hands” (253), paradoxically controlling her own physical life by giving power over it away to her husband. Oroonoko’s spectacular brutalization commands most of our attention, but Behn wants us to see Imoinda’s as well. Unlike his, hers happens in the day-to-day and as a matter of course. When Behn celebrates her great beauty—the beauty that marks her as Oroonoko’s romantic equal—she thus also makes us see Imoinda’s pain, her scars. Praising Imoinda’s “modesty and her extraordinary prettiness,” Behn’s narrator also notices that she is “carved in fine flowers and birds all over her body” (48). Imoinda’s body registers an indigenous African body art not constrained by the European standards that Behn asserts elsewhere: “I had forgot to tell you,” says Behn’s narrator,

that those who are nobly born of that country are so delicately cut and ra[z]ed all over the fore part of the trunk of their bodies that it looks as if it were Japanned, […] the works being raised like high points round the edges of the flowers. Some are only carved with a little flower or bird at the sides of the temples, as was Caesar; and those who are so carved over the body resemble our ancient Picts that are figured in the chronicles, but these carvings are more delicate. (48)

Why did the narrator almost “forg[e]t to tell” us about Imoinda’s beautiful scars? Why is she telling us about them now? Perhaps because they have always been there, taken for granted in something of the way that the earth itself—evoked in Imoinda’s “flowers and birds,” the tree-like “trunk” of her body—is taken for granted, and wounded so “you” can live. The word “world” appears again and again in a novella whose action covers a good part of the globe. Imoinda’s body here is a world. Not just a natural world but a world of nations: it is “japanned” (seeming lacquered), it recalls the “ancient Picts” of Britain who were also tattooed, it is created through the indigenous arts of Africa, and it brings to mind the vegetation we see in Surinam. Imoinda is the world, Behn seems to say, the world at its best, harmonious and fertile and diverse.

So it is no wonder that “Imoinda” is the last word of Oroonoko. It’s an unusual name that Behn probably made up. But we cannot help but notice the first letter—“I”—that links her to the “I” of the female narrator. And the second syllable, “moi,” is the French word for “me,” tightening that link while reminding us that this is a name that incorporates the beauties of many different languages. The slave name imposed on Imoinda, Clemene, is all but forgotten. But the word “Clemene” recalls the idea of “clemency,” meaning forgiveness and, ultimately, grace. In the brutal world of power that Behn depicts, “the beautiful and the constant Imoinda” leaves open the possibility of grace.

Works Cited

Behn, Aphra. Oroonoko, ed. Janet Todd. Penguin, 2003.

Brown, Laura. “The Romance of Empire; Oroonoko and the Trade in Slaves.” In Oroonoko: An Authoritative Text, ed. Joanna Lipking. Norton, 1997, pp. 232-46.

Sussman, Charlotte. “The Other Problem with Women: Reproduction and Slave Culture in Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko.” In Oroonoko: An Authoritative Text, ed. Joanna Lipking. Norton, 1997, pp. 246-55.

Jayne Lewis is a professor of English at UC Irvine, a faculty lecturer in the current cycle of Humanities Core, and the director of the Humanities Honors Program at UCI. Her most recent book, Air’s Appearance: Literary Atmosphere in British Fiction, 1660-1794 (Chicago, 2012) looks at how, when and where “atmosphere” emerged as a dimension of literary experience–an emergence which links the history of early fiction with those of natural philosophy and the supernatural. She is also the author of The English Fable: Aesop and Literary Culture, 1650-1740 (Cambridge, 1995), Mary Queen of Scots: Romance and Nation (Routledge, 2000), and The Trial of Mary Queen of Scots: A Documentary History (Bedford, 2000). Her present research and much of her ongoing teaching focuses on middle modern generic forms in relation to changing narratives of illness and healing, including a course on the “sick imagination” that explores illness narratives from the Book of Job through 21st-century poetry and graphic fiction.

Jayne Lewis is a professor of English at UC Irvine, a faculty lecturer in the current cycle of Humanities Core, and the director of the Humanities Honors Program at UCI. Her most recent book, Air’s Appearance: Literary Atmosphere in British Fiction, 1660-1794 (Chicago, 2012) looks at how, when and where “atmosphere” emerged as a dimension of literary experience–an emergence which links the history of early fiction with those of natural philosophy and the supernatural. She is also the author of The English Fable: Aesop and Literary Culture, 1650-1740 (Cambridge, 1995), Mary Queen of Scots: Romance and Nation (Routledge, 2000), and The Trial of Mary Queen of Scots: A Documentary History (Bedford, 2000). Her present research and much of her ongoing teaching focuses on middle modern generic forms in relation to changing narratives of illness and healing, including a course on the “sick imagination” that explores illness narratives from the Book of Job through 21st-century poetry and graphic fiction.