John Hamilton Mortimer, Etching of Caliban from Twelve Characters from Shakespeare (1775). From the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This post was originally published on February 5, 2018.

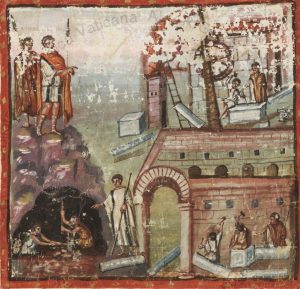

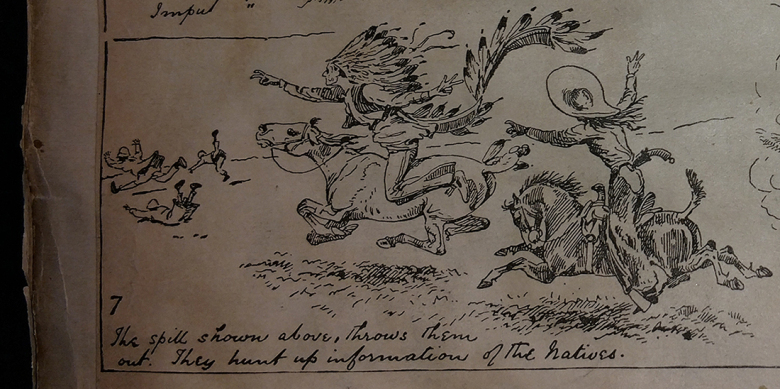

Listening to Dr. Lewis’s lecture today about who the island belongs to, I was reminded of when I first read Shakespeare’s The Tempest in high school. I couldn’t figure out who or what Caliban was. On a first reading, it seems a little ambiguous whether he is a supernatural creature, a monster, or just as human as Prospero and Miranda. In the cast of characters at the beginning of the book, he is called “a savage and deformed slave,” with no other mention of his inhumanity (2). Yet, in the early illustrations of the play, he is almost always depicted as a fishy monster, probably in response to Trinculo’s description of Caliban as “A strange fish” (II.ii.28). If we continue listening, however, Trinculo goes on to say that “this is no fish, but an islander that hath lately suffered by a thunderbolt” (II.ii.36-38). Even more curiously, in one of those delightful moments of breaking the fourth wall of the stage, Trinculo critiques the audience listening to him, saying that English people wouldn’t give a penny to a poor beggar, but they’ll “lay out ten to see a dead Indian” (II.ii.34). Although most signs point to a small Mediterranean island as the setting of The Tempest, is it possible that we are also meant to read Caliban as an “Indian,” that is, someone from the New World?

We can begin exploring the answers to this question by looking at Shakespeare’s sources. One of the things I’d like to do in this blogpost is introduce you to the enormous wealth of digitized books available on the internet, particularly through a service called Early English Books Online (EEBO), which includes virtually every piece of material published in English between 1473 and 1700. Although the story of The Tempest seems to be original to Shakespeare (unlike most of his other plays), he was inspired by a number of other texts. One source that has begun gaining more attention recently is Peter Martyr d’Anghiera’s early compilation of New World accounts from the early days of colonization. Although this Italian historian wrote in Latin for the Spanish crown, his De Orbe Novo was translated into English in 1555 as Decades of the New World by Richard Eden. It compiles the accounts given by Gonzalo Ferdinando de Oviedo of his time colonizing the Caribbean, the rivalry between King Ferdinand II of Spain and Naples and Alonso King of Portugal (Afonso V), Ferdinand Magellan and his pilot Antonio Pigafetta’s circumnavigation of the globe, the voyages of Sebastian Cabot, and even mentions a “greate devyll Setebos” worshiped in Brazil (219; discussed in Stritmatter & Kositsky 25-34, passim). Do any of these names sound familiar? Although there is no mention of a Prospero or a Miranda, there is a great deal of discussion surrounding cannibals in the “West Indies” and South America, a subject we will return to momentarily.

First page of Sylvester Jourdain’s “A Discovery of the Barmudas” (1610). Full text available on Early English Books Online.

In 1611, when Shakespeare wrote The Tempest, the British did not yet have any colonies in the Caribbean. They had, however, just discovered an island in the Atlantic under wondrous circumstances involving a shipwreck. As Dr. Lewis noted in her lecture today, The Sea Venture was blown off-course en route to the Virginia colony, and then wrecked off of coast of the Bermudas, where they spent the next nine months (rough life!). They later built two boats and sailed to the Jamestown colony, and the news of their survival was published in 1610 by one of the sailors, Sylvester Jourdain, in A Discovery of the Barmudas. Jourdain claims that “the Ilands of the Barmudas, as every man knoweth that hath heard or read of them, were never inhabited by any Chiftian or heathen people, but ever esteemed, and reputed, a most prodigious and inchanted place, affording nothing but gusts, stormes, and foule weather,” and thus they have been shunned by European explorers and settlers of the New World (8). However, as Sommers and his crew discovered, it was “the richest, healthfullest, and pleasing land… and merely natural, as ever man set foote upon” (10). As far as I have been able to research, the Bermudas were not inhabited by other people when the English settlers were shipwrecked there. Yet there were both pigs and tobacco on the island when these castaways arrived, neither of which are native to those islands, which suggests that they were brought from somewhere else. In the official True Declaration of the Estate of the Colonie in Virginia, also published in 1610, this was chalked up to God’s providence in providing for the English mission of the new world, for it “increaseth wonder, how our people in the Bermudos found such abundance of Hogs…” (23). Another source often held up as an inspiration for Shakespeare’s play is William Strachey’s account of the Sea Venture Shipwreck, “A True Repertory of the Wreck and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight,” in which he surmises that the pigs came as the result of having “escaped out of some wracks” previous to the tempest that drove Sommers and his crew there. Although this report was not published until 1625 as part of Samuel Purchas’ Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas His Pilgrimes, it is possible that Shakespeare had seen a draft of this report prior to writing The Tempest since he was an investor in the Virginia Colony (Vaughan & Vaughan 11-12). (Nerd alert: The digitized copy of Purchas available through archive.org was originally owned by John Adams, second president of the United States, and you can see his signature in the top right corner of the title page.) Dr. Lewis made the case that these convergences of shipwrecks, and a stormy island reputed by most to be inhabited by devils or spirits, (and I would add the apparently providential supply of pigs) might lead us to believe that these accounts of Bermuda shaped the “qualities” of Caliban’s island (I.ii:337).

What of Caliban himself? As Jourdain says, Bermuda was “never inhabited by any Chiftian or heathen people,” so how did this character come to be there? Shakespeare tells us that his mother Sycorax, a witch from “Argier” (Algiers), gave birth to him on the island after she had been exiled there (I.ii. 263-284). Since Alonso and his company have recently come from a wedding in Tunis, these locations in North Africa should bring our attention back to the Mediterranean (II.i.72-74). In the 19th century there was a theory that Caliban’s name came from an Arabic insult, يا كلب [ya kalib], meaning “you dog” (Vaughan & Vaughan 33). Just like today, Arabic was the common language of North Africa, so it is possible that Shakespeare had somehow heard this expression and decided to use it in his play. Whether or not this is true, it is important that Caliban’s name was given by his mother, not by Prospero. Just like the names Sycorax, Setebos, and Ariel, Caliban does not have a clear European origin.

Sebastiano del Piombo, Portrait of a Man, Said to be Christopher Columbus (1519). From the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Another etymology, one I find more convincing, is that Caliban’s name is related to the word “cannibal.” Shakespearean scholars since the late 18th century have noticed that Caliban’s name is an anagram of the Spanish spelling of this word: canibal (Vaughan & Vaughan 26). We can date with precision the day that this word first came into contact with European languages, since it is a loan word from the Caribbean and is first recorded in Christopher Columbus’s journal of his first voyage to the New World. On Friday, November 23, 1492, a little more than a month after first landing in the Bahamas, Columbus was off the coast of Haiti. Some natives of the Greater Antilles who were on board warned him about the men who lived there:

The wind was East-Northeast, and they could shape a southerly course, but there was little of it. Beyond this cape there stretched out another land or cape, also trending east, which the Indians on board called Bohio [Haiti]. They said that it was very large, and that there were people in it who had one eye in their foreheads, and others whom they called canibales, of whom they were much afraid. (English translation by Clements R. Markham, slightly revised)

When Columbus introduced this word to Europe upon his return, it did not yet mean what we usually think of. Instead, it referred to a specific people who lived in the Eastern Caribbean. The men on board who warned Columbus were Taino or Lucayans, groups that spoke closely related Arawakan languages in the Western Caribbean. The neighbors they feared were a different group of people who lived in the Eastern Caribbean islands and on the northern coasts of South America. These people are the Kalinago, called Caribs in English, and in fact, the words ‘Carib,’ ‘cannibal,’ and ‘Caribbean’ all come from their name.

Taino and Island Carib Territories map from The Decolonial Atlas

How did this come to be? It is difficult to say much with certainty about the languages of the native inhabitants of the Caribbean in 1492. But using historical linguistics we can make educated guesses about the word Columbus may have heard and why he wrote it down the way he did. In the Kari`nja [or Kali`nja] language spoken by the Kalinago today, the word kari`na means “human being,” and Karinago means “the people.” However, the /r/ used to spell this language does not correspond to the same [r] sound we have. Instead, it refers to [ɽ] a sound made by flicking the tongue very quickly against the alveolar ridge behind your teeth. To someone who doesn’t speak Kari`nja [kaɽiɁnʲa], this might sound like an [r] or an [l], which is why their name is variously transcribed as ‘Carib,’ ‘Kali`na,’ ‘Kari`nja,’ ‘Kalinya,’ ‘Cariña,’ ‘Carib,’ or even ‘Galibi.’ Behrend Hoff, a linguist who specializes in Cariban languages, suggests that this word was originally *kari:pona in prehistory (“Language Contact” 35). After the speakers of this prehistoric language spread apart to different parts of the Caribbean, the word came to be pronounced differently in various dialects, and it was also borrowed into other languages like Taino. This could account for how the word took so many written forms. Thus, in modern Arawak (spoken by the Lokono people in Suriname and neighboring Guyana), the word has become karipna; the Garifuna, descendants of Island Caribs and Africans who live on the eastern coasts of Central America, took the word as their name; in the jungles of southern Venezuela, another Cariban group call themselves the Carihona (Aikhenvald 41-43). The dispersion of Carib groups across present-day Venezuela, Suriname, and Guyana led this region to be labeled Caribana on many early maps of South America (Vaughan 28-29). On Columbus’s ship in November of 1492, the word *karibna may have been pronounced *kanibna because the western dialects of Taino did not have an [r] sound and often replaced it in loanwords with [n]. Thus Columbus wrote “caniba,” “canima,” and “canibal” over the course of his journal. But it is possible that eastern Taino speakers would have said *kalibna, that is, Caliban.

It is often claimed that the word cannibal came to have its more familiar meaning because the Caribs that Europeans encountered in the New World really did eat human flesh. However, there is very little direct evidence that this is true. The first time the charge of man-eating is leveled against the Caniba it is second-hand. On December 17, 1492, Columbus’s records his disbelief when his Taino guides accuse the “canibales” of eating their enemies:

The sailors were sent away to fish with nets. They had much intercourse with the natives, who brought them certain arrows of the Caniba or Canibales. They are made of reeds, pointed with sharp bits of wood hardened by fire, and are very long. They pointed out two men who lacked certain body parts, giving to understand that the Canibales had taken bites out of them. The Admiral [Columbus] did not believe it. (English translation by Clements R. Markham)

Although Columbus never saw Caribs eating other people, this accusation is repeated several times in his journal, and is picked up in the accounts of other early European explorers. What Columbus did not know in 1492, but historians now suspect, is that the Taino felt that they were in competition with Caribs over territory. One reason to suspect this is that the inhabitants of the Lesser Antilles in the late 15th century called themselves Carib, but spoke an Arawakan language called Iñeri. To distinguish them from the Caribs who lived on the mainland of South America, Europeans came to call these people Island Caribs, and they later discovered that the Island Carib men spoke Iñeri in public and to their families, but spoke a reduced version of a Cariban language among themselves. The traditional explanation of this anomaly is that Caribs from the mainland invaded these islands by force, killed and ate all of the men, and then took the women as wives a few generations before Columbus’s arrival, thus creating a gender distinction in language. These same Island Caribs were then encroaching on the islands of the Greater Antilles, such as modern-day Puerto Rico and Haiti.

Whatever the truth might be (and we will return to this later), some strife between themselves and the Carib led the Taino to spread anti-Carib propaganda to their new Spanish “allies.” Although there is no good evidence for the practice of cannibalism among Island Caribs, there is direct evidence from Columbus’s journal and from later adventurers that Island Caribs violently resisted European colonization. And as Philip Bouchard has written, the Spanish found these “grossly distorted charges of man-eating” quite useful in justifying the enslavement and depopulation of Carib people. “Whatever the reality of Island Carib practices, Europeans created the myth of Caribs as ferocious, insatiable cannibals. As with some other peoples who resisted European incursions, Caribs found themselves saddled with this indictment” (7). We might recall here Matthew Restall’s claim that Europeans saw the native inhabitants of the Americas as “cultureless, innocent, or nefarious” (105) and note that these characterizations seem to develop immediately upon contact between Columbus and the people of the New World. Roberto Retamar, a Cuban intellectual, makes this division of nefarious and innocent specific to the Taino and the Caribs in the way they received Spanish colonization.

The Taino will be transformed into the paradisical inhabitant of a utopic world; by 1516 Thomas More will publish his Utopia, the similarities of which to the island of Cuba have been indicated, almost to the point of rapture, by Ezequiel Martínez Estrada. The Carib, on the other hand, will become a caníbal – an anthropophagus, a bestial man situated on the margins of civilization, who must be opposed to the very death. (Retamar 6-7)

In the Fall Quarter we saw how Jean-Jacques Rousseau used the Khoisan (i.e. “Hottentot”) people to frame his rejection of “progress,” but we should also recall that the people he refers to as “the people that until now has wandered least from the state of nature” are Caribs (65). Rousseau might be thinking here of Montaigne‘s “On the Cannibals,” which we read for class today and which depicts the Tupinamba people of the Amazon and their rituals of eating human flesh. Yet it also paradoxically praises the nobility of these cannibals:

It is a nation… that hath no kind of traffic, no knowledge of letters, no intelligence of numbers, no name of magistrate, nor of politic superiority; no use of service, of riches, or of property; no contracts, no successions, no partitions, no occupation but idle; no respect of kindred but common, no apparel but natural, no manuring of lands, no use of wine, corn, or metal. The very words that import lying, falsehood, treason, dissimulations, covetousness, envy, detraction, and pardon, were never heard of amongst them. (qtd. in Shakespeare 103)

If that English translation rings a bell, it is because Shakespeare borrows liberally from it in Gonzalo’s speech about what he would do with Prospero’s island if he were given control of it (II.i.152-61, 164-69). Montaigne’s Essais were translated into English in 1603 by John Florio, one of Shakespeare’s close friends. So we know that Shakespeare was reading Montaigne, and probably also reading Peter Martyr’s account of New World exploration. So when he named Caliban, did he have in mind the noble savage crushed by European colonization, or was he instead thinking of a nefarious man-eater who would kill his neighbors given the chance?

The word “cannibal” does not appear in The Tempest, but Shakespeare does make use of it in some of his earlier plays, each time in reference to a bloody, violent people. In Othello, he makes it explicit, calling them “the Cannibals, that eat each other” (I.iii.473). This is the same way that both Purchas and the English translation of Peter Martyr unambiguously use the term. In the earlier text, there is still an etymological connection observed between the word cannibal and Carib: “The wylde and myschevous people called Canibales, or Caribes, whiche were accustomed to eate mannes flesshe…” (27). Sixty years later when Purchas was writing, this link had been severed, and he could state that Caribs “are certain Canibals, which used inhumane huntings for human game, to take men for to eate them…” (730). This has lead many to see Caliban’s name as an indictment of his character, a not-so-subtle hint that Prospero’s slave, like other cannibals, is “inhumane.”

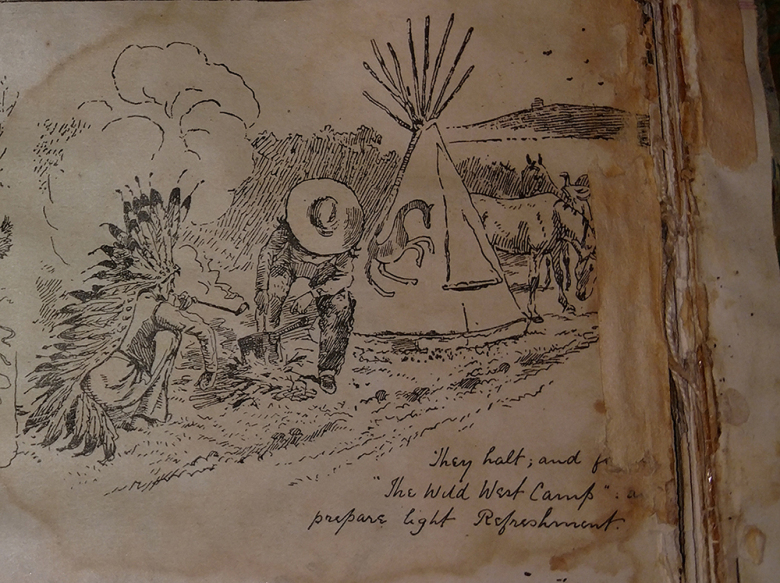

Joos van Winghe (designer) and Theodor de Bry (engraver), Depiction of Spanish atrocities committed in the conquest of Cuba in Las Casas’s “Brevisima relación de la destrucción de las Indias” (1663). Image from Wikipedia.

But other interpretations are possible. Between 1585 and 1604, England and Spain were in a state of constant but undeclared war, and there was a great deal of Anti-Spanish propaganda circulating in London when Shakespeare was writing his plays. One piece in particular, published in 1583, was entitled The Spanish Colonie, or Briefe chronicle of the acts and gestes of the Spaniardes in the West Indies, an English translation of Bartolomé de las Casas’s Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias. This book lays out a devastating eyewitness account of the genocide and cruelty perpetrated by the Spanish in the Caribbean. De las Casas was a Dominican missionary sent by the Spanish crown to convert the Taino, and he lamented that although their souls could be saved, most of them were dead by the time he arrived:

Upon these lambes so mecke, so qualified & endewed of their maker and creator, as hath bin said, entred the Spanish incontinent as they knew them, as wolves, as lions, & as tigres most cruel of long time famished: and have not done in those quarters these 40 yeres be past, neither yet doe at this present, ought els save teare them in peaces, kill them, martyre them, afflict them, torment them, & destroy them by straunge sortes of cruelties never neither seene, nor reade, nor hearde of the like (of the which some shall bee set downe hereafter) … We are able to yield a good and certaine accompt, that there is within the space of the said 40 years, by those said tyrannies & devilish doings of Spaniards …into death unjustly and tyrannously more than twelve Millions of soules, men, women, and children. And verily do believe, and think not to mistake therein, that there are dead more that fifteen Millions of soules. (De las Casas 10-11)

Historians dispute the accuracy of these numbers, and this text is very much a part of the Black Legend that we heard about from Restall (118-119). It is undeniable, however, that Spanish diseases, enslavement, and outright slaughter killed the majority of the native peoples of the Caribbean. This is one of the reasons that we will never know if it were Tainos or Lucayans who introduced the word kanibna to Columbus. His first landfall was in the Bahamas, the homeland of the Lucayans, a few of whom he kidnapped and tortured for information about where to find gold. When Columbus returned as the “Governor of the Indies,” he imposed a tax on every Taino man to produce either one pound of gold or twenty pounds of cotton every year. When people refused, he cut off their hands. Further expeditions from Spain to the Caribbean lead to the outright enslavement and deportation of most of the native inhabitants of the Bahamas to be slave laborers on Hispaniola. By the time de las Casas left Hispaniola, the Lucayans had been completely annihilated, and the Taino population was cut in half. De las Casas says that 500,000 people lived in the Bahamas before Columbus’s arrival; after the last eleven people were deported in 1520, the islands were considered “uninhabited” until 1648, when it was recolonized by the British, just like Bermuda. Indeed, another theory for why Island Caribs spoke both Iñeri and Carib is, according to Boucher, that “in historical times Island Caribs received constant infusions of Arawakan-speakers. Some of these were prisoners of war from the Greater Antilles; others, especially those from Puerto Rico, were refugees from Spanish persecution. Island Caribs, their numbers thinned by Old World diseases and by Spanish slave traders, no doubt integrated, especially the Arawakan women.” This is not to suggest that the Spanish were uniquely cruel. After all it was the British who, after taking the independent island of St. Vincent by force in 1796, slaughtered most of the Garifuna and deported the survivors almost two thousand miles away to the coast of Honduras, a journey upon which half of the prisoners died.

The descendants of these people still live today along the coast of Central America. Their music and culture are world renowned, as you can see in this 2013 music video for “Móungulu” by The Garifuna Collective, a group based in Belize who sing in Garifuna.

English brutality towards the residents of St. Vincent began more than a century and a half after Shakespeare died. Perhaps, like Shylock in the Merchant of Venice, Caliban represents a problematic, misunderstood, but very human character. In the context of the Anglo-Spanish wars and the Black Legend, it is possible that we are meant to sympathize with poor Caliban suffering under Prospero’s heel (as Dr. Lewis mentioned, Milan in Shakespeare’s day was ruled by the Spanish Habsburgs). Although it is unlikely that Shakespeare knew this, it seems like more than mere coincidence that Caliban’s name means “human being” in the Cariban languages, and that his last words in the play highlight his intention to “seek for grace,” whatever that might entail (V.i.296). For Roberto Retamar, Caliban is the symbol of the Caribbean people and their struggles against European colonialism.

This is something that we, the mestizo inhabitants of these same islands where Caliban lived, see with particular clarity: Prospero invaded the islands, killed our ancestors, enslaved Caliban, and taught him his language to make himself understood… I know of no other metaphor more expressive of our cultural situation, our reality. (Retamar14)

It is not impossible that Shakespeare might have agreed.

Works Cited

Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. The Languages of the Amazon. Oxford, UK: Oxford UP, 2012. Print.

Boucher, Philip P. Cannibal Encounters: Europeans and Island Caribs, 1492-1763. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1992. Print.

Hoff, Berend. J. “Language Contact, War, and Amerindian Historical Tradition: The Special Case of the Island Carib,” Wolves from the Sea: Readings in the Anthropology of the Native Caribbean. Edited by Neil Whitehead. Leiden: KITLV Press, 1995. 37-60. Print.

Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford, UK: Oxford UP, 2003. Print.

Retamar, Roberto Fernández. Caliban and Other Essays. Translated by Edward Baker. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002. Print.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Basic Political Writings. Translated and Edited by Donald A. Cress. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2011. Print.

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. Edited by Robert Langbaum. Newly Revised Edition. New York, Signet Classics, 1998. Print.

Stritmatter, Roger A. and Lynne Kositsky. On the Date, Sources and Design of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2013. Print.

Vaughan, Alden T. and Virginia Mason Vaughan. Shakespeare’s Caliban: A Cultural History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

Ben Garceau is a scholar of early medieval and late antique literature with particular interests in early Britain, translation studies, and critical theory. He received a dual Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and English from Indiana University in 2015. His work has appeared in PMLA, Translation Studies, and the Yearbook of Comparative Literature. He has also contributed to the HC Research Blog on the topic of textual criticism and the Aeneid. When he isn’t leading seminars in Humanities Core, he likes hiking, working on his science fiction novel, and digging through record shops.

Ben Garceau is a scholar of early medieval and late antique literature with particular interests in early Britain, translation studies, and critical theory. He received a dual Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and English from Indiana University in 2015. His work has appeared in PMLA, Translation Studies, and the Yearbook of Comparative Literature. He has also contributed to the HC Research Blog on the topic of textual criticism and the Aeneid. When he isn’t leading seminars in Humanities Core, he likes hiking, working on his science fiction novel, and digging through record shops.