The post originally appeared in Surfacing Memory: Seeking the Voices that Inform Me, a multimedia site where seminar leader Susan Morse explores artifacts and heirlooms in an effort to reconstruct her own family’s history. Our gratitude to Dr. Morse for sharing this personal story here in hopes that it will serve as a model for Humanities Core students’ own oral history and artifact-based research projects this quarter.

“Do not judge your neighbor until you walk two moons in your neighbor’s moccasins” (Cheyenne Proverb)

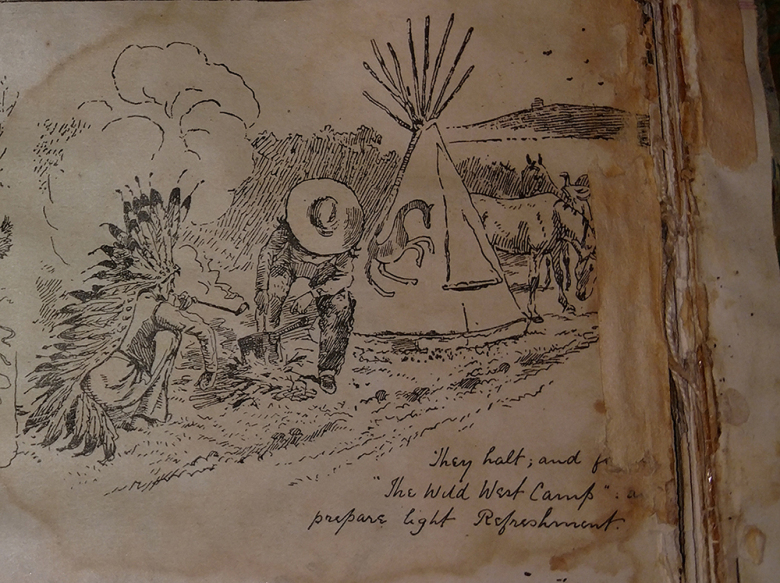

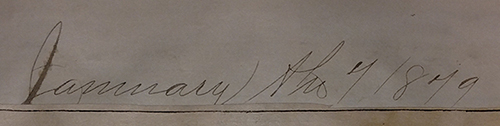

Just above illustrations pictured below was written the date

I’m not sure if this date refers to when the nine panel “funny” was originally published in the newspaper or to when it was pasted in the McNiven (my great great grandmother’s and then Jesse McNiven’s) Scrapbook. There are very few clues to indicate in which newspaper (or in which country) this illustration was even printed. Given my knowledge of the McNiven family time-line, there is a distinct possibility it appeared in a Canadian newspaper prior to the family exodus to the then American territories to the south. Then again, in 1879 they may still have been in Scotland.

I’m not sure if this date refers to when the nine panel “funny” was originally published in the newspaper or to when it was pasted in the McNiven (my great great grandmother’s and then Jesse McNiven’s) Scrapbook. There are very few clues to indicate in which newspaper (or in which country) this illustration was even printed. Given my knowledge of the McNiven family time-line, there is a distinct possibility it appeared in a Canadian newspaper prior to the family exodus to the then American territories to the south. Then again, in 1879 they may still have been in Scotland.

What interests me about these possibilities is that the illustration clearly demonstrates a fascination with empire; in particular with the clear demarcation between the old inheritance-based British Empire and the newly expanding American empire making its presence known deep into the “Wild Western frontier.” What’s more, the panels characterize — or even satirize — a clear cultural dissonance between these positions that makes possible a third and more compelling ethnographic reading outside of empire altogether.

So let’s try walking through this illustration wearing different pairs of moccasins to see how each fits beginning with the caption at the end of the illustration which reads:

![]() Given ethnolinguistic references from the 19th century, it is clear from the caption that an American Indian (pejoratively described as a “Red Shirt”) and a cowboy (also referenced negatively as an untamed or wild “Broncho Bill”) have been invited to a hunting event but one that will not align with their expectations. The superior “Master of Hounds” serves as the host for this occasion, and given this final revelation it seems clear that from a socio-cultural context this event would be both foreign and unknowable to the two American men, something that gives satire some legs. Spoiler aside, the caption confirms the medium’s rhetorical design as one that will draw on cultural dissonance to drive a particular narrative.

Given ethnolinguistic references from the 19th century, it is clear from the caption that an American Indian (pejoratively described as a “Red Shirt”) and a cowboy (also referenced negatively as an untamed or wild “Broncho Bill”) have been invited to a hunting event but one that will not align with their expectations. The superior “Master of Hounds” serves as the host for this occasion, and given this final revelation it seems clear that from a socio-cultural context this event would be both foreign and unknowable to the two American men, something that gives satire some legs. Spoiler aside, the caption confirms the medium’s rhetorical design as one that will draw on cultural dissonance to drive a particular narrative.

Our narrative begins with an American Indian traveling together with a fairly stereotypical characterization of an old “Wild West” cowboy. The two ride together in peace and in harmony with each other and in nature; the horses also moving in step. The teepee and war bonnet place the American Indian in a tribe, like the Cheyenne, that hunts and follows the seasons and the movement of big game; bison in particular. Other noteworthy markers — such as the feathers and long war bonnet — situate the American Indian riding in the front as both his tribe’s leader as well as a singularly courageous and prominent member of his tribe.

Traditionally, tribal members earn their first eagle feather to commemorate a rite of passage into adulthood. I witnessed this ritual annually while coaching and living on the Salish-Kootenai Reservation in Arlee, Montana while I was an undergraduate. Tribal elders presented High School seniors with an eagle feather along with their diplomas at the Graduation ceremony. After the presentations were completed, one of the Tribal Elders explained that the American Indians from the northwest and plains region consider the eagle to be the bravest and strongest of all birds. Not only does this spirit travel with the feather, but also anyone who possesses and wears a ceremonial eagle feather carries honor and pride at being one of the First Peoples (feathers were offered to all non-tribal seniors as well). As a final gesture, the Tribal Elder waved his feathers over the crowd as a means of wishing everyone in the community prosperity, peace and happiness.

Additional feathers are then awarded following actions recognized by the tribe as courageous or heroic. The feathered head dress pictured above, for example, conveys much more than this man’s role as the tribal chief. This war bonnet signals a lifetime’s worth of feathers earned through heroic action. Additionally, the warrior’s pole he carries and the horse he rides contain a number of overflow feathers earned. Finally, both the war bonnet and warrior’s pole are ceremonial, reserved for special occasions, and serve as a sign of respect for the coming event – say, for example, a ritualistic hunt or an invitation to meet with a “neighbor” in the Cheyenne sense of the word.

This ethnographic reading of the two Americans, however, may have been lost on the readers of the time who might have preferred instead to see these men as wild and weak or inferior in comparison to the imperial power whose newspaper they read. The chief, for example, carries his own teepee, a task usually reserved for women in the tribe. This, along with a hyperbolic abundance of ceremonial feathers offers those sympathetic to the British Empire a rhetorical reading of this so-called great and heroic leader as anything but formidable or worthy. The cowboy representative of the American Empire maintains an even weaker position, since he trails behind the chief and rides a paint horse. The paint horse — a mix of Barb, Andalusian and Arabian breeds — was originally brought to the frontier during the Spanish “conquest” of the Americas by Cortez and his Conquistadors. Nineteenth century associations of the paint horse by white colonizers and Europeans were pejorative given its mixed blood, connections with a defeated imperial intervention and its most common association as the “Big Dog” or “God Dog” of the American Indian, in particular with those tribes that hunt and wage war on the plains.

Additionally, although later panels of this illustration clearly name the cowboy as a man, the depiction above not only feminizes him, but it also places him in an even more inferior, weaker position in contrast to the already emasculated chief. His long, free flowing hair characterizes his identity as untamed, wild and therefore “savage” or uncivilized according to beliefs that were widely-held by Europeans (as well as by their descendants living in the established states of America) at this time. As a representative of the American imperial machine, the feminized American stands in sharp contrast to the masculinized British “Master of Hounds” (not yet pictured but named in the closing caption). This man — the “Master” — is a figure with distinction, a man fronting a clear title and legacy bound to a deep, long-standing aristocratic British tradition. Unlike the “Master,” the cowboy bears the name “Broncho Bill.” His identity characterizes him, in part, as a “broncho” (or the more common bronco) which in “Wild West” equestrian circles describes an untamed and untrained “frontier” horse. Interestingly, it is also a term used to denote a mustang, another mixed breed of range pony introduced to the American territories by the Spanish (and which continue to run feral in the hills to this day). Moreover, this man is identified by first name only and does not garner societal distinction enough to hold a family name; therefore this (Imperial agent) “broncho” represents an uncivilized, culturally mixed emasculated man, but this is not a reliable ethnographic reading. Let’s get back to that…

The second panel in the series reflects — on the one hand — a harmonious, symbiotic relationship between the American Indian and his cowboy companion. In this frame, the cowboy prepares what is mockingly described as “light refreshment” presumably for both men as the chief smokes a pipe, a ceremonial gesture signaling agreement with a covenant between parties or preparation for a planned ceremonial event. Perhaps he smokes in this case to acknowledge the invitation to join “the Hunt.” The horse adorning the teepee elevates this animal to a spirit or totem animal that symbolizes a balance between personal drive and untamed passions, between individual agency and a responsibility to others, quite suitable given the chief’s role in his community. Harmony extends also to the two horses standing behind the teepee that have been acculturated to two different traditions, and that live and rest comfortably together which parallels the two men who bear markers to clearly different yet compatible ways to exist and to live together.

On the other hand, the designation of this space as a “Wild West Camp” recalls earlier depictions of the American representative of empire as uncivilized and weak. What’s more, the cowboy performs a woman’s labor by preparing the refreshment and probably also by serving the chief who currently smokes alone. I’m partial to the symbiotic and harmonious reading, of course, but as someone who studies this history, I must acknowledge the generosity of such a narrative in hindsight given widespread and systematic atrocities perpetrated against the First Peoples by agents of American imperialism in the 19th and 20th centuries.

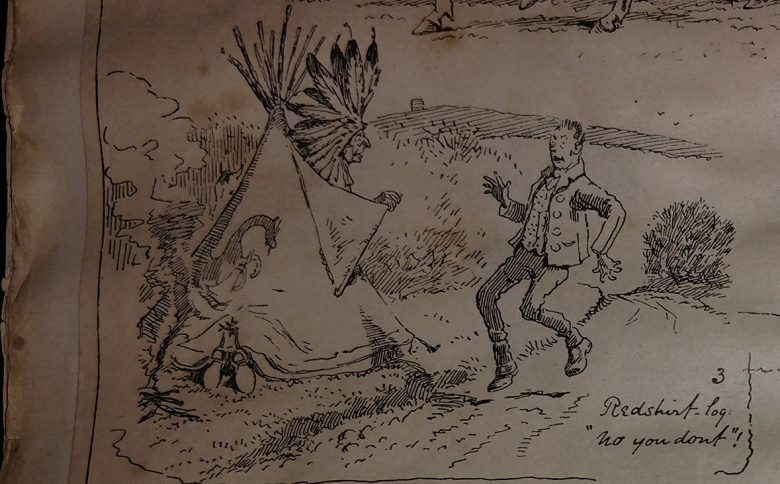

Negative attitudes about the First Peoples were perpetuated in part through cultural dissonance (through the notion of a “gender frontiers,” for example), the implications of which are clearly depicted in panel three. It appears that a well-dressed local (looks a little “dandy” to me) on an afternoon walk has just happened on the cowboy and the chief engaging in some afternoon teepee relations — so to speak — with the chief having taken a superior position. This interaction sharply mocks American colonizers (represented by our “broncho”) as having succumbed to or been seduced by the so-called “unnatural behaviors” of the “savage” American Indians.

Additionally, the depiction of the chief places him in an overtly sexually aggressive stance counter to the man passing by. This exchange facilitates what might have counted in 19th-century America as a threat to white culture; first, through a mixed race, same-sex relationship and second, through the aggressive encounter triggered by the exposure of, what looks like, a naked and virile “Indian” chief to the startled, unarmed white stranger shown as innocently passing by. The cultural reality, however, is that heteronormative ideals and constructs didn’t really exist among American Indian tribes until they were imposed on them by European colonizers. And — as an interesting aside that the illustrator may not have known — American Indian hunters traditionally abstained from intercourse for a few days prior to a hunt as part of a ceremonial practice (abstinence from sex to produce an abundant bounty during the hunt).

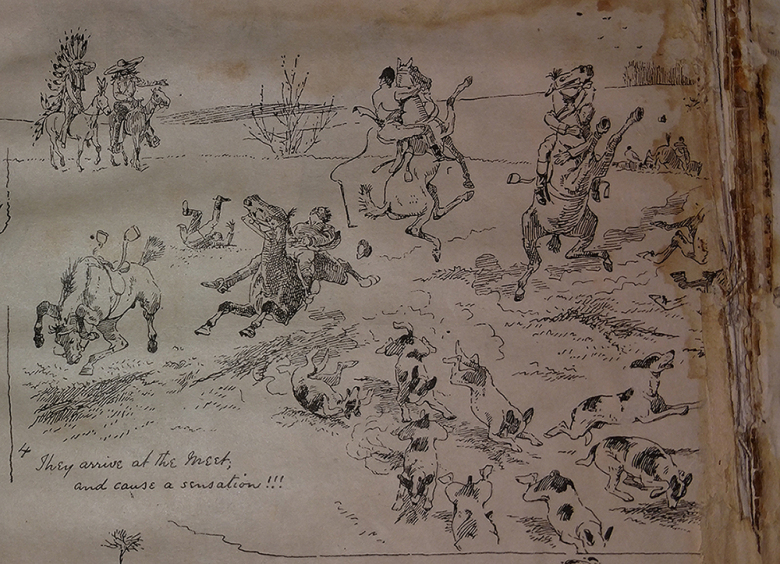

The threat of a blended culture to imperial civilization and legacy continues to figure prominently in panel four. Clearly, the sight of the American Indian chief and “Wild West” cowboy seems so strange and “savage” in contrast to the waiting members of the British hunting group, that neither the “civilized” men nor beasts among them including the dogs can control its feelings or “sensation[s]” of desperation. At the same time, and funnily, the two Americans calmly and quietly enter the scene to witness pure chaos as the well-dressed, British fox hunters struggle to sit or to control their mounts and hounds marking a clear dissonance between the cultural groups.

The cultural disconnect depicted in this frame and implied throughout the illustration extends primarily to the differences between what counts as a hunt for each group. The British riders with their hounds are waiting for a Fox Hunt, a sport of leisure (pffft) that goes back to the 16th Century that does not yield any food as bounty for a successful run. The primary objective of this kind of hunt is the performance of human superiority over animals, of wielding control over a pack of trained dogs to chase down and to kill the red fox. These unarmed riders (chasers more than hunters) work together with the “Master” of the hounds to control and to direct their hounds as they search for, chase down, and kill a fox victim. The Master may then choose to reward those hunters who perform most admirably during the event with some trophy from the dead fox — a paw, the mask, or the tail (the biggest honor). The remaining carcass is then tossed to the hounds. Very civilized indeed and then light refreshment follows.

However, one doesn’t have to look beyond the above panel to recognize that the chief and his partner had a much different hunt in mind. The chief who is positioned as standing and surveying the landscape in front of him, clearly, searches for big game — most likely bison — as the objective of the hunt. This hunt does not describe a mere sport for those in the American “frontier.” The hunt for bison (buffalo where I come from) which may last a single day or several, ideally yields tens of animals all of which are honored, eaten, worn and otherwise utilized by members of the tribe. No part of the animal goes to waste. In terms of a hunting bounty, the hunter responsible for bringing a buffalo down with his bow and arrow is entitled to claim the hide and some of the choicest meat cuts as his prize.

An even more special prize for American Indians — like the Cheyenne — is marked by a hunter’s first kill, where as his trophy and as an important rite of passage, he will drink some of the blood of his kill. While drinking the blood of a freshly killed animal may seem at first savage (and certainly would for the Fox Hunters), this is in reality a culturally short-sighted position. American Indians live in harmony with nature, belong to the land and see themselves as brothers to the animals they kill. Blood symbolizes the force that gives life to all beings. The blood, along with the animal that sacrifices it, is a gift that deserves and demands respect (a message my Navajo godfather Jimmy John relayed to me throughout my childhood). A hunter who drinks the warm blood of the animal he has killed demonstrates his deep respect for the animal’s sacrifice. It also symbolizes that the life of this animal will continue in the hunter. In death, the animal’s body (and blood) serves as a gift that will ultimately prolong the lives of many in the hunter’s tribe. Given this naturalist reading of the scene, the calm entry of the two men signifies their harmonious relationship with nature, with their horses and with each other.

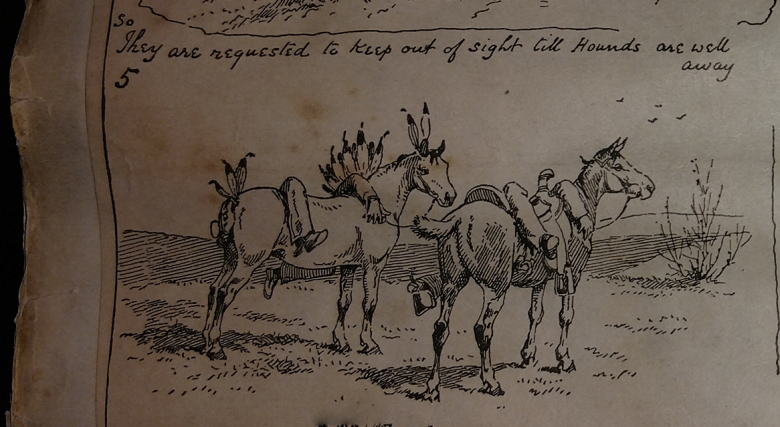

The British hounds, however, are not in harmony with this nature but express such a discord at the sight of these two individuals and their horses that the American men must hide until the more “civilized” and trained hounds will no longer be negatively affected (or even influenced) by their presence (which really pushes the “othering” boundaries).

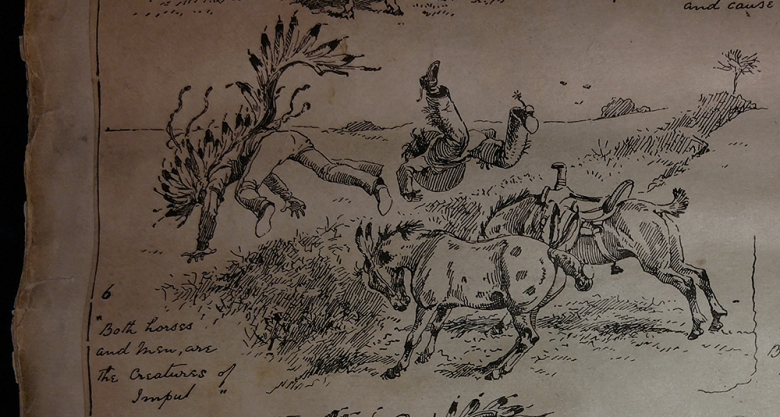

Throughout these panels, the harmony and symbiosis of the two American men persists, despite rhetorical efforts to depict them as weak, emasculated and inferior. This symbiosis and harmony between the men, their horses and their inner nature or “impulse” continues in frame six as the men are thrown from their mounts. It is unclear what particular impulse led to this unexpected ejection (perhaps it simply mocks them as irrational creatures), but the double stop of the horses and the double flight of the men further illustrates an equity between these two men even though they clearly come from different cultural backgrounds (and from different equestrian traditions). They remain in harmony with each other and with the natural world including with their inner “impulse.” And their horses aren’t getting ready to run away from the men (which you’ll notice on the next frame).

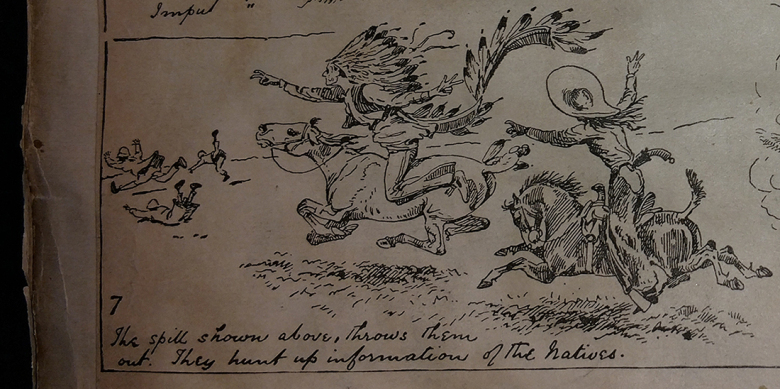

In panel seven the two Americans are back on their mounts and chasing after “information” about some “natives” depicted above that look quite like British citizens, don’t they? In fact, these “natives” resemble 19th-century bobbies, a police force first put in place in London in the early 19th century to maintain law and order on the British home-front. Perhaps the spoof here is on the American wanton disregard for the British imperial claim on the western territories. These two “wild” Americans lack the decorum to perform accordingly at the Fox Hunt. Their very presence disrupts the event precisely because they are “savage” outsiders or “others” in the context of European Imperialism. Further taking the above panel into account, they wildly chase these “natives” without control over their own trajectory (or their mounts) at the same time as they fail to recognize the so-called “native” claim to the land as conferred by the panel’s caption. There is a sharp irony that features one of the First Peoples in this fight against the “natives”: one, because he travels with a member of the American Imperial team and two, because the British bobbies claim “native” ownership, which, as we know, was but one of many attempted European interventions on territory already fully populated by a diverse, self-regulating, autonomous indigenous population.

Have you noticed a clear lack of narrative between some of these panels? So have I! Two consistent features, however, seem to be the persistence of satire and the two Americans. The above scene, for example, satirizes “frontier” scouting techniques, although it is quite unclear what these men are trying to find, and where the third guy came from. Maybe they are still scouting for the “information” they were seeking in the previous panel. The above depiction of “Broncho Bill” mocks his lack of scouting skills as he presumably uses his hand to reach for scat and other tangible clues about the particular “scent” they seek. The illustration pokes further fun by depicting the American Indian as literally utilizing a white man to accomplish this same task (which seems much more practical) and which degrades the white man’s and the cowboy’s ethos. In reality, however, American Indian scouts enjoy a long-standing reputation as quasi-diviners who can detect and read seemingly obscure natural signs, or pick up a trail by vibration and sound, or observe and gather vital knowledge about an enemy without detection.

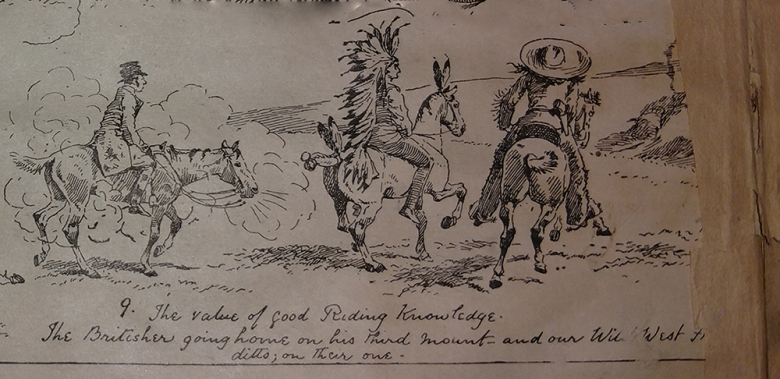

And so we come to the final frame in the series, which appears to answer a few unanswered questions, offers a clear commentary about the two American riders, and throws an additional means for understanding the “hunt” into conversation. As it turns out, the hunt and the scouting excursion seem, in the last few frames, to have been to locate one of any available run-away horses for the British rider to carry him back home. Although many of these panels have promoted a claim of British superiority, when it comes to real riding, this Brit and his mount look spent. In this panel, the Brit trails behind both American riders who begin and end their journey on their own horses, illustrating that they are both good riders and possess “good riding knowledge,” perhaps a positive nod to having “impulse” that may be akin to sound horse sense. This stands in stark contrast to the Britisher who was dismounted and who lost control of three different horses. It doesn’t appear that he even travels home on his own horse. Also noteworthy is that while there were consistently negative characterizations of the two American men, they are referred to in these final lines as “our Wild West friends” who (you may have noticed) have been riding and working together for some panels now.

“Our Wild West friends” bring me to the final tidbit about this peculiar illustration. According to the caption that follows this final panel (the one we began our discussion with), the hunt was set to meet in Hertfordshire, but there is no Hertfordshire in America or in Canada. The closest is a county located in southern England. After all of this consideration and analysis, in the end, it is possible this illustration may not have been published or set on the North American continent at all but rather took place in the 19th-century British imagination.

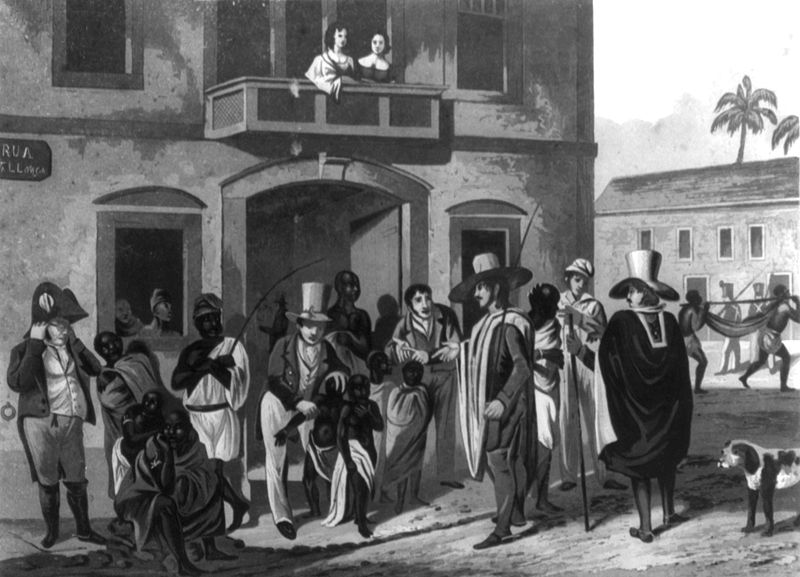

Perhaps this illustration nods to early iterations of the “Wild West” spectacles, the most famous of which are the Buffalo Bill Wild West Shows. If you do any digging, you’ll certainly notice a lot of Bills as headliners (Pawnee Bill, Buckskin Bill, Buffalo Bill…Broncho Bill). Smaller versions of these shows began in England in the early 1870s and featured an array of “frontier” types that fed consumer curiosity about “unnatural” oddities of the American “Wild West” including cowboys, American Indians, infamous outlaws, lady sharp shooters, etc. These curious figures were all put on public display and observed and marveled and consumed for their “strange” manners like any number of traveling “freak shows” and other marvels of nature that were popular in Europe in the 19th century. Is it possible that “Our Wild West Friends” depicted as living in symbiosis and harmony with each other and in nature were actually meant to stand in as marvels of nature in a kind of illustrated “Wild West Freak Show” published in a British newspaper way back on January 1, 1879? If that was the intention, then the joke is on them for having missed the deeper meaning. I think I prefer walking around in my neighbor’s moccasins for a few moons…

After Professor Sharon Block’s lecture on Thursday, April 13th, I decided to add a postscript:

The moccasins to the left above are mine and were made in the traditional way. Men perform the hunt and women perform the remaining labor. They dress the animal, prepare the meat, other animal parts, and hide: scrape, tan, chew (yes, you read that correctly) and smoke the leather. The bead work was done by Jeannie Peak whose mother is very famous in the region for traditional beaded crafts she made for famous people like the Queen of England and Roy Rogers (of old Western Film and Radio Spectaculars). Many members of the area tribes — including many of my Salish friends in Arlee, MT — are descended from American Indians converted in the late 1800s to Catholicism (see the Mission in St. Ignatius, MT). The flower on the two pieces above is the “Salish Rose,” symbolic of femininity, fertile bounty (reproduction), and the natural cycles of life. The Salish Rose also has a second meaning that most outside of the community might not know; it is a symbol of the Catholic Sacred Heart of Christ. The second piece — the necklace featured to the right above — is traditionally worn by Salish women who participate in tribal and intertribal dancing ceremonies and rituals called Pow Wows (during fourth of July weekend in Arlee). The Shawl Dance or the Traditional Dance are danced by the American Indian woman to celebrate her femininity, her role within the tribal community, and her direct connection to mother nature.

Susan Morse is a continuing lecturer in the Humanities Core Program at UC Irvine, where she has enjoyed teaching for many years. She received her PhD in German Studies from the UCI Department of European Languages & Studies in 2006. She also studied Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, Psychology and English at the Universities of Montana and Arizona, which is another reason why she loves teaching in the Humanities. Her research focuses on Holocaust memory and the limits of representation in the Holocaust. In addition to leading seminars in Core, she also enjoys teaching a Romantic Fairy Tales course for the Department of European Languages & Studies and Comparative Literature.

Susan Morse is a continuing lecturer in the Humanities Core Program at UC Irvine, where she has enjoyed teaching for many years. She received her PhD in German Studies from the UCI Department of European Languages & Studies in 2006. She also studied Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, Psychology and English at the Universities of Montana and Arizona, which is another reason why she loves teaching in the Humanities. Her research focuses on Holocaust memory and the limits of representation in the Holocaust. In addition to leading seminars in Core, she also enjoys teaching a Romantic Fairy Tales course for the Department of European Languages & Studies and Comparative Literature.