“What is my nation? Who talks of my nation?”

Shakespeare’s Henry V, Act 3, Scene 2

What separates an empire from a nation?

![Hans Ulrich Franck, Der Geharnischte Reiter [Knight in Armor] (1603-75). Etching.](https://sites.uci.edu/humcoreblog/files/2016/10/Screen-Shot-2016-10-26-at-12.36.32-PM.png)

Hans Ulrich Franck, Der Geharnischte Reiter [Knight in Armor] (1603-75). Etching.

When I asked my students this question during our first seminar, they offered two very apt responses. First, they suggested, empires are relics of the past, and now we only talk seriously of nations. Second,

if and when we do use the word “empire” today, they observed, it’s almost always negative: a label you attach to political or cultural entities that you consider corrupt or undesirable (e.g. when Ronald Reagan called the Soviet Union the “Evil Empire” during the Cold War); whereas “nation” evokes positive feelings of belonging and encourages pride in your ethnic or cultural heritage.

Both observations accurately capture our contemporary attitudes and assumptions, and they reveal the great extent to which the nation-state – “an area where the cultural boundaries match up with the political boundaries” – is now regarded as the most natural and efficient form of political organization possible. But as should be apparent from our lectures in HumCore thus far, this has not always been the case. In fact, the concept of the nation-state itself did not even come into being until the 17th century, and its elevation to the preferred form of political community didn’t happen overnight but instead progressed slowly over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. So, as we transition from Professor Zissos’s lectures on the Roman Empire to Professor Steintrager’s on the European Enlightenment, it will be helpful to think about how this thing we call the nation-state came into being and how it conditioned European attitudes toward empire that would ultimately influence our own. In doing this, we will be following a scholarly method pioneered by the preeminent French philosopher Michael Foucault called genealogy, which is an attempt to discover the origins, and explain the historical evolutions, of our contemporary concepts, social behaviors, and values.

Population loss in Germany during the Thirty Years War

As it happens, the origin of the nation-state was a topic covered in the last cycle of Humanities Core, which centered on the theme of “War.” In that cycle, Professors Jane Newman and John Smith, both from UCI’s Department of European Languages and Studies, gave a series of lectures on the legacy of the Thirty Year’s War (1618 – 1648), a devastating conflict that ravaged central Europe (mostly in the area of present day Germany) and killed almost a third of the continent’s population before hostilities ceased. (NB: all the previous cycles of HumCore are archived on the program’s website, so you can find the materials for these lectures here if you’d like to explore the subject further.) And as Professors Newman and Smith explained, the extremity of the Thirty Year’s War arose from a number of factors.

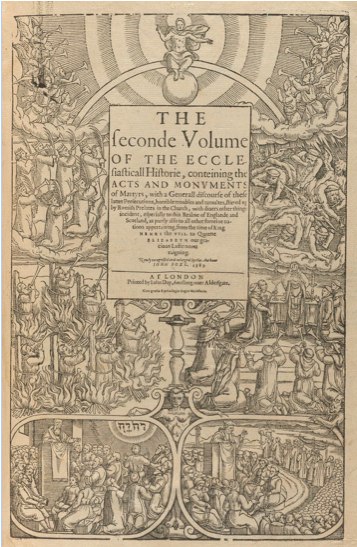

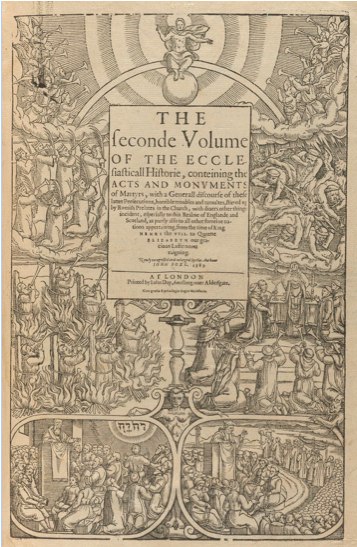

First, it was a war based on religious identity, where Protestants and Catholics both refused to recognize each other’s right to rule their own lands and assumed a kind of divine sanction for invading the other’s territories. Though both forms of Christianity, Protestants and Catholics saw each other in antagonistic and apocalyptic terms during the 16th and 17th centuries, with each defending their own doctrines as absolute truth while attacking their opponents as sinfully corrupt, almost demonic. In the context of England, which is my area of research, this extreme religious prejudice can be seen in the title page of John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments (1563), a history published under Queen Elizabeth I that chronicled Catholic persecutions of Protestants.

John Foxe, Actes and Monuments (London, 1563). Houghton Library Collection at Harvard University.

Starting at the bottom of the image (right), we can see how the two forms of Christian practice (Protestant on the left, Catholic on the right) are contrasted. Moving up the page, the Protestants on the left undergo holy martyrdoms celebrated by a trumpeting chorus of saints and angels. On the right, the Catholic ritual of the Eucharist is literally figured as devil worship, by its positioning beneath a cloud of jeering demons. Christ himself sits in judgement, blessing the Protestant side with his raised hand, while condemning the Catholic with a lowered one. Within the pages of the Acts itself, Foxe, like many other Protestant propagandists of the age, equated the papacy with the biblical figure of Antichrist, claiming that the Catholic Church had falsely usurped the ancient authority of the Roman empire and had used it to unlawfully tyrannize over the whole of Christian Europe. As Foxe writes in Book 1 of the 1576 edition of the Acts:

Insomuch that they [the Popes] have translated the empire, they have deposed Emperors, Kings, Princes and rulers and Senators of Rome, and set up other, or the same again at their pleasure; they have proclaimed wars and have warred themselves. And where as Emperors in ancient time have dignified them [popes] in titles, have enlarged them with donations, and they receiving their confirmation by the Emperors, have like ungrateful clients to such benefactors, afterward stamped upon their necks, have made them to hold their stirrup, some to hold the bridle of their horse, have caused them to seek their confirmation at their hand, yea have been Emperors themselves. (29, original spelling and diction modernized)

To call this an attitude leaving little room for compromise or diplomacy would be an understatement.

Second, the Thirty Years War was fought mostly by mercenary forces in the pay of various European noblemen, rather than by the kinds of well-disciplined and publicly funded armies that characterize modern nation-state militaries. As a result, soldiers were given to unrestrained rape and pillage of the civilian population, taking food and other resources that they needed to sustain their campaigns from local farms and towns. In short, it was the kind of total, chaotic war comparable to the conflicts involving Syria and ISIS happening today.

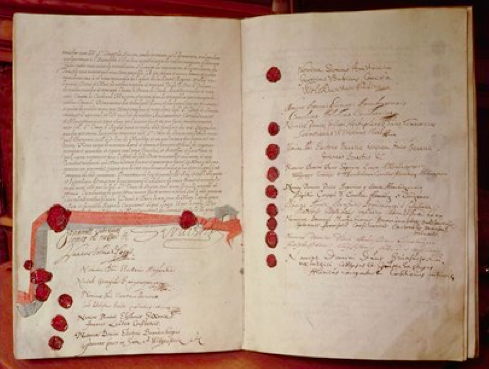

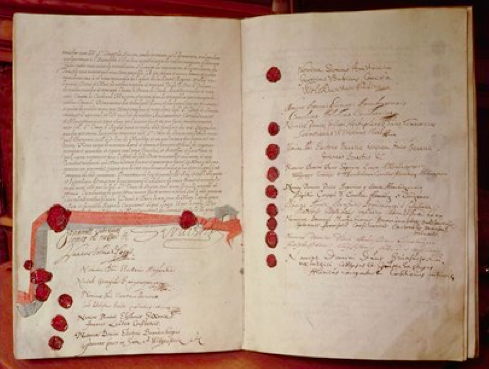

The Treaty of Westphalia (1648)

But the lasting significance of the Thirty Year’s War, as Professors Newman and Smith argued, came from how it ended. Weary of the prolonged carnage, the various sides finally came together to negotiate the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. With 109 signatories, the treaty settled a number of key issues for international relations in Europe. First, it defined (and thus ended disputes over) a number of contested borders, producing an exact map of European national territories for the first time. Second, it upheld the principle that each country had the right to abide by whatever religious identity its ruler chose, a principle encapsulated in the Latin phrase cuius regio, eius religio (“whosever realm, his religion”). Finally, it acknowledged that each nation had sovereignty over its own domestic affairs, which should not be subject to interference by any outside power. And thus, the nation-state was born: the “nation” part coming from the common identity produced by the relatively homogenous cultures and religious affiliations contained within the borders of each country; and the “state” part coming from this inchoate principle of sovereign self-determination.

The Treaty of Westphalia also signaled the weakening of religion’s hold over the political, moral, and intellectual outlook of European society – a trend that would reach full expression in the Enlightenment a century later. Take, for example, the concept of sovereignty that Westphalia established. In some ways it is similar to Roman imperium, as both denote a kind of absolute authority to command and order society it rules over, but importantly sovereignty claims neither to be universal (i.e. it applies only within the recognized borders of an individual nation) nor divinely sanctioned. Moreover, it was during the period of the Thirty Year’s War that the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes developed his influential theory of government and politics, a theory that based political authority, which Hobbes calls sovereignty, on materialist reasoning rather than religious belief.

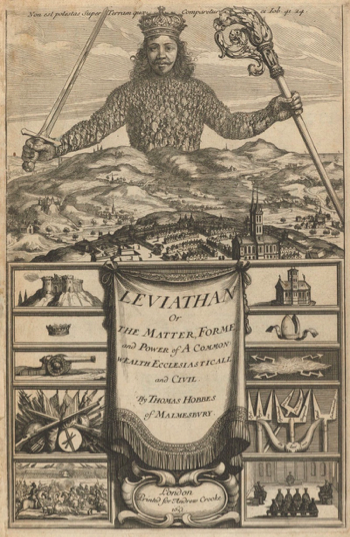

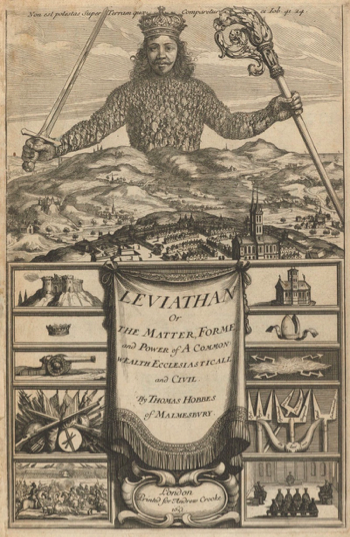

Abraham Bosse, Frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan. London (1651). Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

According to Hobbes’s account, humans form governments in order to escape the “state of nature” – a condition in which there are no laws and individuals are in a constant state of war with each other for resources and dominance. In his most important work Levithan (1651), Hobbes offers the following description of what life in this state of nature would have been like:

In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. (Book I, Chapter XIII)

Thus Hobbes argues that, In order to escape the miseries of the state of nature, individuals come together to form a “social contract,” an agreement whereby they give up their liberty to do whatever they want and place themselves under a common power (i.e. sovereign), who will keep the peace, enforce laws, and maintain order. In Leviathan’s striking title page (right), or frontispiece (which has been an endless source of scholarly interpretation itself), we can see the basic principles of Hobbes’s new philosophy rendered visually, as the sovereign’s body is allegorically composed of all the individual subjects that have legitimized his power through the social contract.

Moreover, by looking at the iconography of Hobbes’s earlier work, we can appreciate the extent to which Hobbes consciously intended for his philosophy to pry European ideas about government from the religious foundations upon which they had previously rested.

Jean Matheus, frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes, De Cive (Paris,1642). Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Consider, as evidence for this intention, the frontispiece to his work De Cive (“On the Citizen”) (left), which was published a few years before Leviathan and is where Hobbes’s most important concepts, like the state of nature and social contract, were first articulated. Note how the work’s title page includes a Christ in judgement at the very top, similar to the religious iconography that animated Foxe’s title page we saw earlier. But here a horizontal division is created in addition to the vertical one, whereby the lower half of the image offers Hobbes’s conceptual replacements for the apocalyptic dualism above. On the left, the figure of Imperium – representing government, order, and civilization – stands with sword and scales before a background of cultivated fields and industrious production. On the right, Libertas, figured as a Native American with bow and spear, represents the state of nature, before a background depicting scenes of war and competition. Thus, Hobbes visually replaces the theological categories of salvation (i.e. an eternal reward for correct religious belief and practice) and damnation (i.e. the eternal punishment for failing to believe and practice correctly) with the secular categories of civil society and the state of nature, and what he’s essentially saying to his European readers is that state authority, and each individual’s loyalty to it, should be determined by its observable ability to prevent worldly disorder, rather than its uncertain relationship to religious truth.

So, now that we’ve sketched a brief genealogy of the nation-state, how might we use it to enrich our understanding of the material that we will be encountering during Professor Steintrager’s series of lectures?

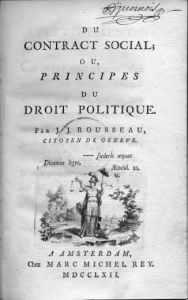

One way is to ask ourselves how the legacy of Westphalia and the Hobbesian emphasis on natural origins were taken up and re-interpreted by our assigned Enlightenment writers. For example, consider Kant’s definition of enlightenment as “the human being’s emergence from his self-incurred minority,” which is in many respects a translation Westphalian sovereignty to the level of the individual. Rousseau, on the other hand, offers a mixed set of attitudes toward the legacy of 17th century thought. He would himself take up the question of social contract, but unlike Hobbes, who considered human life in the state of nature to be wretched, Rousseau elevates nature to such an extent that he perceives greater virtue in those untouched by civilization.

Second, as we move into the topic of the British empire, it’s important to remember that it was an empire that developed after the invention of the nation-state, meaning that its organization, administration, and ideology should offer interesting distinctions from the kind of empire practiced by the Romans. What does it mean to have an empire with a nation-state at its center? Does the nation-state produce an empire that is more colonial in nature than the empires that existed before the nation-state? How did the sovereignty of the British monarchy operate differently within the borders of the United Kingdom than it did in the greater territories of the empire?

Or perhaps, even after producing our historical genealogy of the nation-state, might we still consider that nation and empire may not be that different after all?

Works Cited

Kant, Immanuel. “What is Enlightenment?” Political Writings. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991. 56-60. Print.

Robin S. Stewart received his Ph.D. in English from UC Irvine in 2013, specializing in early modern British literature and Shakespeare. In its various forms, his research focuses on how pre-modern and early modern texts can offer productive opportunities for rethinking the origins of, as well as supplying alternatives to, our contemporary cultural assumptions and values. His most recent publications are “Last Judgment to Leviathan: The Semiotics of Collective Temporality in Early Modern England” in Temporality, Genre, and Experience in the Age of Shakespeare: Forms of Time, Ed. Lauren Shohet (Arden Shakespeare, Forthcoming 2017) and “Early Modern Drama & Emerging Markets,” in Routledge Companion to Literature & Economics, Ed. Michelle Chihara & Matthew Seybold (Routledge, Forthcoming 2018). In addition to teaching in the Humanities Core Program since 2014, he teaches upper-division courses on Renaissance literature and Shakespeare, as well as writing courses in UCI’s Program for Academic English/ESL. He spent this past summer giving a talk on Chinese adaptations of Shakespeare in Hong Kong, seeing a lot of local theater, and preparing for the birth of his first child, due this December.

Robin S. Stewart received his Ph.D. in English from UC Irvine in 2013, specializing in early modern British literature and Shakespeare. In its various forms, his research focuses on how pre-modern and early modern texts can offer productive opportunities for rethinking the origins of, as well as supplying alternatives to, our contemporary cultural assumptions and values. His most recent publications are “Last Judgment to Leviathan: The Semiotics of Collective Temporality in Early Modern England” in Temporality, Genre, and Experience in the Age of Shakespeare: Forms of Time, Ed. Lauren Shohet (Arden Shakespeare, Forthcoming 2017) and “Early Modern Drama & Emerging Markets,” in Routledge Companion to Literature & Economics, Ed. Michelle Chihara & Matthew Seybold (Routledge, Forthcoming 2018). In addition to teaching in the Humanities Core Program since 2014, he teaches upper-division courses on Renaissance literature and Shakespeare, as well as writing courses in UCI’s Program for Academic English/ESL. He spent this past summer giving a talk on Chinese adaptations of Shakespeare in Hong Kong, seeing a lot of local theater, and preparing for the birth of his first child, due this December.

Kurt Buhanan earned his PhD at UC Irvine, and has published on German literature and film, visual culture, and critical theory. He has articles on the poet Paul Celan and the contemporary filmmaker Christian Petzold forthcoming in the journals Semiotica and The German Quarterly, respectively. Unlike Bertrand Russell, he does not hold Rousseau responsible for the rise of Hitler, but he would be happy to discuss the point.

Kurt Buhanan earned his PhD at UC Irvine, and has published on German literature and film, visual culture, and critical theory. He has articles on the poet Paul Celan and the contemporary filmmaker Christian Petzold forthcoming in the journals Semiotica and The German Quarterly, respectively. Unlike Bertrand Russell, he does not hold Rousseau responsible for the rise of Hitler, but he would be happy to discuss the point.

![Hans Ulrich Franck, Der Geharnischte Reiter [Knight in Armor] (1603-75). Etching.](https://sites.uci.edu/humcoreblog/files/2016/10/Screen-Shot-2016-10-26-at-12.36.32-PM.png)