This essay first appeared on Saturday, January 29th on Susan Morse’s Humanities Core website Empires Will Fall, where she blogs alongside the students in her seminars. She has graciously shared this post with the Humanities Core Research Blog.

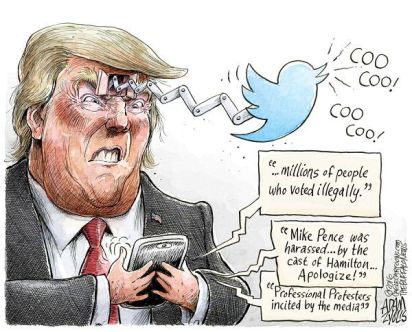

Andrew Zyglis, “Twitter Tirades.” Originally published in the Buffalo News, November 29, 2016.

Yesterday was January 27th, and for some people it was just another Friday, another step toward a weekend marked perhaps with overestimated potential or targeted for solitary reflection or some other form of leisure. For others, this day signaled the end of an insufferably long presidential premiere filled with a flurry of carefully choreographed executive orders signed by our newly sworn in “intimidater” and chief, or as others in the social media world have donned him, our “reprimander” and chief. For me, yesterday has meaning that moves far beyond the banality of the every day and toward the impulse diplomacy now being practiced with dangerous consistency by our late night “tweeter” and chief, my personal favorite of his nick-names. I guess what I have come to realize is that after just a few days in office, yesterday began the first day of the end of strategic and formal American diplomacy as I have experienced it during my medium young life-time and the potential return to shameful policies best left in the past.

Yesterday was International Holocaust Remembrance Day, established by the General Assembly of the United Nations to commemorate the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp on January 27, 1945. As a holocaust scholar, I have spent years reflecting on the slow but legalized process of removing Jewish members from their rightful place in German society in the years following Hitler’s rise to power. Initially, Jewish citizens were intimidated then compelled to leave their homes to escape the persecution made possible with the September 15, 1935 establishment of the Nuremberg Laws. Recognizing the clear dangers of remaining in Nazi Germany, some families – early on – were able to leave and to begin a new life elsewhere. However, as Hitler passed legislation to freeze Jewish assets and began closing the Reich’s borders to prevent Jewish families from leaving the nation without first paying an Exit Tax, it became next to impossible for these citizens to escape the very real dangers that this newly burgeoning empire presented to them. Only a few prominent or otherwise lucky individuals with outside connections, like Sigmund Freud, were “sponsored” financially by patrons willing to purchase their freedom and to ensure their continued existence.

Although the willing executioners sympathetic to the Nazi cause are remembered as the grand perpetrators of the Holocaust, an unforgivable and unfathomable act of human evil in the 20th Century, the list of other complicit nations is long and should not be forgotten. Our very own United States government under Franklin Delano Roosevelt played its own shameful part.

John Knott’s cartoon “Please, Ring the Bell for Us,” July 1939.

In February 1939, months before the cartoon to the right fully expressed the general unwillingness of the United States government to intervene in Hitler’s anti-Semitic agenda, two public servants called for responsible action. NY D-Senator Robert Wagner and MA R-Representative Edith Rogers offered for consideration a bi-partisan piece of legislation that would grant safe passage and sponsored refuge to 20,000 Jewish children under the age of 14. This call to action corresponded with some other national efforts at the time to save Jewish children and families from Nazi occupied Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. The most well-known of these efforts, England’s Kindertransport, saved close to 10,000 Jewish children in a nine month period between 1938 and 1939. Meanwhile in the United States, the Wagner-Roger’s Bill shamefully did not even pass through committee for a vote opportunity, with opponent arguments ranging from the claim that the nation couldn’t allow 20,000 individuals beyond the then immigration quota to the fear that these children would one-day grow up to take American jobs from other citizens; either way, these are inexcusably flimsy arguments against a clear-cut moral imperative.

During that same year, another event – the tragic journey of the MS St. Louis – further informs this history and day of remembrance. In June, 1939, 900 Jewish mothers, children and other family members were on their way to Cuba to join their husbands, fathers, and brothers, who had gone before them to establish a foundation for a new beginning. After spending several days off the coast of Cuba, at a distance so close that families could hear and see one another, the ship was turned away where it headed to the coast of Florida to make a final plea for refuge. It was not long before the MS St. Louis was also refused entry by President Roosevelt and was forced to make what must have been an unbearable return journey. As disheartening as it is to know that nearly one third of these people were captured and murdered by the Nazis, it is also unsettling to discover Hitler made an example of this failed refugee journey in a major propaganda campaign that highlighted the idea that these Jews were so undesirable, that no nation would accept them. [Editor’s note: In the past few days, an activist Twitter called St. Louis Manifest has been using images of Jewish refugees turned away at US borders to make a poignant commentary on Trump’s immigration ban.]

Our nation did not accept those war refugees in 1939, and it was shameful. Following the end of WWII, the United States revisited its policies, establishing the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1952, which “removed all racial barriers to immigration and naturalization and granted the same preference to husbands as it did to wives of American citizens.” Further reforms were put in place in 1965 and again in the 1970s, making this a nation that welcomed war refugees. I’m sure many of us have family members who came to this country as a result of political tyranny or due to war. In my case, the two surviving members of my Armenian family put down their roots in America after escaping the village of Parchang in Turkey in the early 1900s.

Why have I gone to such lengths to revisit this history? It is precisely because yesterday, President Trump dishonored these traditions as well as International Holocaust Remembrance Day when he made an announcement that he had signed yet another executive order. This is one which steps United States policy back to 1939 and brings us full circle to the beginning of my blog when I first drew attention to the dangerous implications of Trump’s Impulse Diplomacy. Here are just a couple examples from this, Trump’s first week in office:

On January 23rd, while standing in front of the CIA memorial wall, honoring the sacrifice of American field agents, who died in service of our nation, Trump first uttered the phrase that has since become his most recent mantra regarding the Iraq War that, “if we kept the oil you probably wouldn’t have ISIS because that’s where they made their money in the first place. So we should have kept the oil. But okay. Maybe you’ll have another chance. But the fact is, should have kept the oil.” This not only has dangerous implications for the men and women in the military currently assisting Iraqi troops in their campaigns against ISIS, but it also blows up US-Middle Eastern relations. Also, didn’t he say during his campaign that ISIS was Obama’s fault?

On January 24th, following publication of climate science data, images from the poorly attended inauguration, and other factual evidence that doesn’t meet with the president’s approval, Trump responded by ordering a Media Blackout on multiple government agencies. This ban required that targeted agency Twitter accounts (e.g., EPA, USDA, Department of Interior, National Parks) be closed and that all public announcements and data receive government approval prior to publication. [Editor’s note: Here is an NPR round-up on the many rogue Federal Twitter accounts that have sprung up in the past week as protest.]

On January 25th, Trump signed an executive order to take “steps to immediately plan, design, and construct a physical wall along the southern border,” in order to “achieve complete operational control of the southern border.” Trumps repeatedly promised during his campaign and more recently via his “diplomatic” Twitter feed that Mexico would pay for it. Later that night, during his first Presidential interview with ABC News reporter David Muir, he was reminded that the Mexican President had unequivocally stated that Mexico would not pay for a wall, to which Trump’s response was: “He has to say that. He has to say that. But I’m just telling you there will be a payment. It will be in a form, perhaps a complicated form. And you have to understand what I’m doing is good for the United States. It’s also going to be good for Mexico.”

On January 26th, following Trump’s Twitter taunts, his “Wall” executive order, and his ABC News interview, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto canceled his scheduled, traditional “meet and greet” visit to the White House. Trump succeeded in blowing up US-Mexican relations, but he still plans on building the wall, which will most certainly place the burden of payment on U.S. taxpayers.

And yesterday, on January 27th, on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Trump announced the executive order, which takes our country back in time to its 1939 era policies. This is a “Muslim Ban,” designed to protect the nation from “Islamic Terrorism.” It prevents citizens belonging to seven Muslim nations from entering the United States for at least 90 days until serious vetting can be completed. The nations targeted are: Iraq, Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen. The order also indefinitely suspends the admission of Muslim refugees from Syria (but it will allow for Christian refugees from Syria).

Just to be clear here – Trump was elected as the Republican candidate, and he has a Republican Congress. Ultimately, the flurry of executive orders that he has signed throughout his first week in office definitively illustrates that his impulsive govern-by-the-gut practice is not limited to his foreign diplomacy. Regarding the “Muslim Ban,” Trump has repeatedly stated that preventing acts of violence against American citizens from “Islamic Terror” is one of his highest priorities. So let’s take a minute to process. The 9-11 attacks were perpetrated by citizens from Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, and Egypt, all countries not included on the executive order. Other attacks or attempted attacks on US soil going back to 9-11 include the shoe bomber (from England), the underwear bomber (from Nigeria), the San Bernadino shooters (he is from America, she is from Pakistan), the Fort Hood attacker (from the United States), the Boston Bombers (from Kyrgyzstan), and the Orlando Night-Club attacker (from the United States). Okay, none of these individuals are from the nations included on the “Muslim Ban,” either, so what’s the point? Optics for his supporters while safe-guarding his Big Oil Agenda? I’d say Big Oil Empire building gets a big Yep!

The good news, if there is some to glean from this muck of a new administration, is that some of these executive orders won’t necessarily lead to the desired end, beyond having offered the president his photo op, because they require Congressional approval for minor things like the allocation of funding and resources (e.g., building the “Wall,” moving forward with the pipeline projects – #standwithstandingrock). The executive order calling for a complete investigation into voter fraud in the 2016 election goes beyond the authority of the President, because only the Department of Justice or the FBI have authority to make this call and only after they have established evidentiary justification for such an investigation – meaning that it is founded on the basis of having real facts in hand rather than on the basis of Trumpian alternative facts. With respect to the most recent executive order, the “Muslim Ban,” which impacts visitors, refugees and green card holders, it is possible that this is an illegal action altogether.

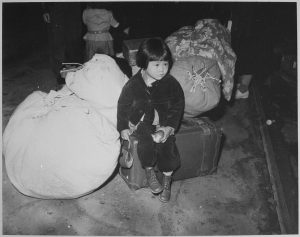

Photograph taken at the Women’s March on Washington, D.C., January 21, 2016.

Regarding the image above, “Japanese Americans against Muslim Registry”- Right. Ya, the U.S. did that too during WWII – I have made a couple of personal resolutions. One, I will voice my dissent often and loudly so long as is necessary. And Two, if Trump eventually signs a “Muslim Registry” executive order – which he may be waiting to do until February 19th to align himself with President Roosevelt, who signed Executive Order 9066 to intern 100,000 Japanese-Americans in their own home country – then I have decided that I am Muslim. I will sign the registry myself, and I will encourage all non-Muslims to join me in line. Weirdly, he seems obsessed by size, especially by crowd size…

Susan Morse is a continuing lecturer in the Humanities Core Program at UC Irvine, where she has enjoyed teaching for many years. She received her PhD in German Studies from the UCI Department of European Languages & Studies in 2006. She also studied Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, Psychology and English at the Universities of Montana and Arizona, which is another reason why she loves teaching in the Humanities. Her research focuses on Holocaust memory and the limits of representation in the Holocaust. In addition to leading seminars in Core, she also enjoys teaching a Romantic Fairy Tales course for the Department of European Languages & Studies and Comparative Literature.

Susan Morse is a continuing lecturer in the Humanities Core Program at UC Irvine, where she has enjoyed teaching for many years. She received her PhD in German Studies from the UCI Department of European Languages & Studies in 2006. She also studied Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, Psychology and English at the Universities of Montana and Arizona, which is another reason why she loves teaching in the Humanities. Her research focuses on Holocaust memory and the limits of representation in the Holocaust. In addition to leading seminars in Core, she also enjoys teaching a Romantic Fairy Tales course for the Department of European Languages & Studies and Comparative Literature.

Vivian Folkenflik is an emeritus lecturer in the Humanities Core Program, where she taught for over three decades. She is the editor and translator of Anne Gédéon Lafitte, the Marquis de Pelleport’s novel The Bohemians (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009) and An Extraordinary Woman: Selected Writings of Germaine de Staël (Columbia University Press, 1992). She is also the author and archivist of our program’s institutional history at UC Irvine. Her thought and teaching have been at the center of many cycles of Humanities Core, and she continues to act as a pedagogical mentor for seminar leaders in our program. She has blogged previously for the Humanities Core Research Blog on the intersection of race and gender in past course texts.

Vivian Folkenflik is an emeritus lecturer in the Humanities Core Program, where she taught for over three decades. She is the editor and translator of Anne Gédéon Lafitte, the Marquis de Pelleport’s novel The Bohemians (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009) and An Extraordinary Woman: Selected Writings of Germaine de Staël (Columbia University Press, 1992). She is also the author and archivist of our program’s institutional history at UC Irvine. Her thought and teaching have been at the center of many cycles of Humanities Core, and she continues to act as a pedagogical mentor for seminar leaders in our program. She has blogged previously for the Humanities Core Research Blog on the intersection of race and gender in past course texts.