Sebastiaen Vrancx, Aeneas and Achates Outside the Temple of Juno (ca. 1615). Louvre Collection. Image and further information available at the Frick Collection.

This post was originally published on October 14, 2016.

Close Reading, In Translation, With Readers From The Past

Writing your first essay in the Humanities Core Course, a literary analysis of a passage from Virgil’s Aeneid, you will have been reading and re-reading Virgil’s text in Robert Fagles’ translation in order to make claims about the text and find appropriate textual support.

It might be hard at this point to remember exactly what you knew about Virgil’s Aeneid before you started reading it in the context of the Humanities Core. Some of you may have never encountered Virgil or the Aeneid, while others may have read all of the Aeneid before they started the course. Most students, however, will fall somewhere in between these extremes, and soon after you started attending Professor Zissos’ lectures, you started to accumulate information about Roman culture and society and the structure of the Aeneid that turned your reading experience into an informed, guided reading experience.

You can think of this kind of reading experience as part of a discussion — literally so in your discussion sections, but also metaphorically as a conversation with anyone in the past who has read Virgil’s Aeneid and left us a record of his or her reading. A text as old as the Aeneid has produced many such records of past readings, testimonies of readers that can direct our attention in turn to specific aspects of the text that we would have otherwise missed. Reading such accounts allows us to enter into a virtual conversation with past readers that enriches our present understanding of the text. First, let us recall a scene from Book 1:

…, uidet Iliacas ex ordine pugnas

bellaque iam fama totum uulgata per orbem,

Atridas Priamumque et saeuum ambobus Achillem.

constitit et lacrimans ‘quis iam locus,’ inquit, ‘Achate,

quae regio in terris nostri non plena laboris ?

en Priamus. sunt hic etiam sua praemia laudi,

sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt.

solue metus; feret haec aliquam tibi fama salutem.’

sic ait atque animum pictura pascit inani

multa gemens, largoque umectat flumine uultum. (Virgilius Maronis, I, 456 – 465)

Translated by Fagles, in our Penguin edition, as follows:

… — all at once he sees,

spread out from first to last, the battles fought at Troy,

the fame of the Trojan War now known throughout the world,

Atreus’ sons and Priam — Achilles, savage to both at once.

Aeneas came to a halt and wept, and “Oh, Achates,”

he cried, “is there anywhere, any place on earth

not filled with our ordeals? There’s Priam, look!

Even here, merit will have its true reward …

even here, the world is a world of tears

and the burdens of mortality touch the heart.

Dismiss your fears. Trust me, this fame of ours

will offer us some haven.”

So Aeneas says,

feeding his spirit on empty, lifeless pictures,

groaning low, the tears rivering down his face … (Virgil 63)

In this blog post I want to focus on one such example of a past reader’s reaction to this specific passage, a remark by Denis Diderot, the editor of the most famous publication during the European Enlightenment, the Encyclopédie, a friend of Rousseau, and one of the first to write evaluative essays about publicly exhibited paintings:

Un des plus beaux vers de Virgile et un des plus beaux principes de l’art imitatif, c’est celui-ci:

Sunt lacrymae rerum, et mentem mortalia tangunt.

Il faudrait l’écrire sur la porte de son [i.e. a painter’s] atelier: Ici les malheureux trouvent des yeux qui les pleurent. (Diderot 392)

One of the most beautiful verses of Virgil, and one of the most beautiful principles of imitative art, is the following:

sunt lacrimae rerum, et mentem mortalia tangunt.

One ought to write it above the entrance to the painter’s studio: ‘Here the unfortunate ones will find eyes that shed tears for them.’ (my translation, O.B.)

The inscription Diderot proposes for a painter’s door as a reminder for the artist that his supreme aim should be to move the beholder is clearly less a translation of the Latin quotation than a metonymical summary of the whole scene.

What seems to be lost in Diderot’s version is the heart-rending conflict in which Aeneas finds himself caught, between grief (hence his own tears) at being confronted with a rendition of his own past, and hope, which he tries to impart to Achates even as he is crying. This hope is also founded on tears: the tears Aeneas assumes the inhabitants of this strange new land to have shed over his fate. It gives him reason to believe that he and his companions will finally meet with a friendly reception, quite unlike the series of encounters with monsters he has just survived, when he re-traced part of Odysseus’ itinerary on his voyage from Troy before landing in Carthage.

Diderot’s metonymy can be resolved in different ways: Diderot may be admonishing the painter to identify with his subject emotionally (the painter’s tears), or he may exhort him to paint so that someone visiting his atelier will be moved to cry. But what is missing from Diderot’s version are tears of recognition, the tears which Aeneas sheds upon recognizing his father and himself (‘se quoque‘, l.488), depicted in their most desperate moment.

Diderot then proposes that the ideal scene of reception for a painting adhering to this criterion would be for a criminal who carries his secret unrecognized in society to dread the steps leading to the public exhibition space for paintings in his contemporary Paris, the Salon, where a painting depicting his crime would have such a powerful effect on him that he would willingly sign his own sentence.

In quoting the line, as Diderot does, a reader re-contextualizes it. Part of this process is the interruption of the narrative sequence of the original, including its sequence of emotions.

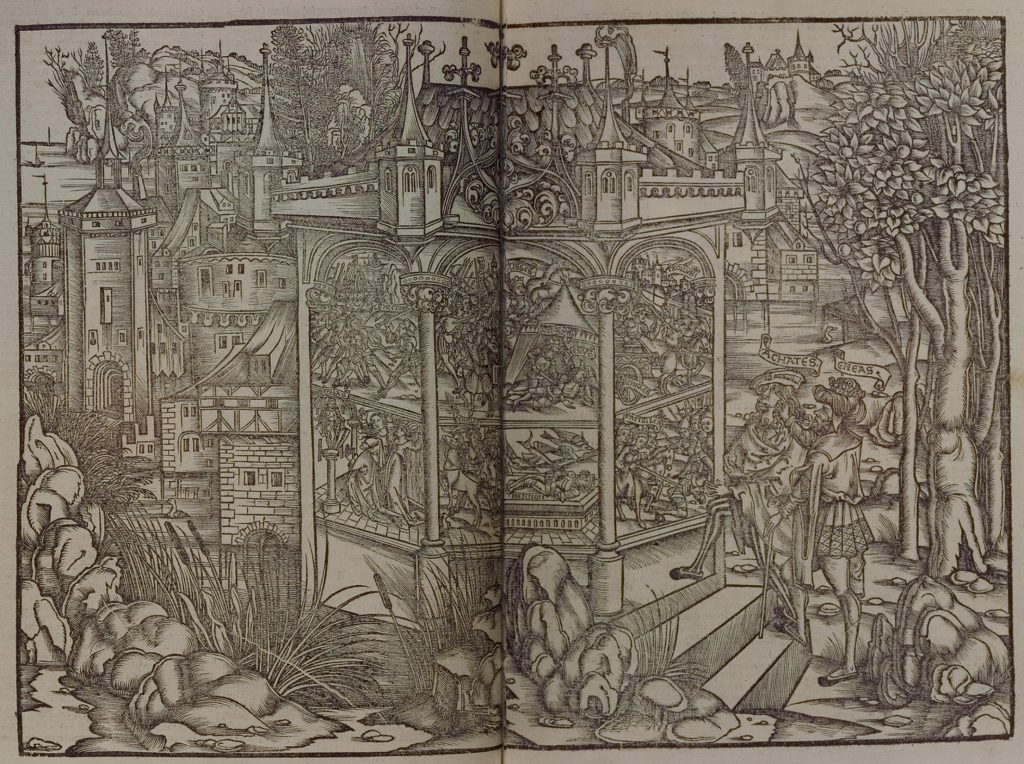

Sebastian Brant, Image of The Mural on Juno’s Temple, Publii Vergilii Opera (Strasbourg, 1502). For more information, see the digitized manuscript at the University of Heidelberg and additional commentary from Dickinson College.

In this particular scene, Aeneas’ conflicted emotions of grief and joy eventually are transferred onto Achates, his companion, who has accompanied him to Carthage from the ships and now stands with Aeneas magically hidden by Venus invisibly before the artwork in Juno’s temple. It is as if Aeneas has brought in the form of his companion Achates his own, representative audience and engages before our very eyes in narrating the temporal sequence of the scene, which most commentators assume to be a mural painting.

And Achates does indeed exhibit the precise mix of fear and hope characteristic of Aeneas’ first reaction: “simul percussus Achates / laetitiaque metuque” (513-4) — Achates was simultaneously shaken both by joy and by fear. But these emotions of Achates are emotions occasioned by Dido, whose appearance with her followers and some of Aeneas’ companions, whom he had left behind at the ships, interrupts Aeneas’ contemplation of the artwork on the wall.

Achates’ reaction might then be described as a delayed emotional reaction that re-enforces the hierarchy separating him from Aeneas — his emotions are slower, he feels only now what Aeneas has felt since he laid recognizing eyes on the representation of scenes from the Trojan War. They also might be described as testifying to the effect of Aeneas’ (and, by extension, Virgil’s) ekphrasis: Aeneas’ re-telling of the scenes that Achates sees in front of him gradually awakens in him the mix of fear and joy Aeneas has been feeling from the very start.

Yet, whatever hierarchical distance between Achates and Aeneas had separated them in their initial reaction is finally effectively closed again in the next line, when both are united in an emotional confusion related to the decision whether or not they should discover themselves to their companions. They both burn with a desire to re-join them, yet they still fear to give up their supernatural disguise for fear that Dido and her people might turn out to be hostile: “auidi coniungere dextras / ardebant, sed res animos incognita turbat” (514-5).

In his commentary on the scene, Lee Fratantuono suggests that Aeneas’ initial mix of fear and joy had to have given way to “increasing horror”:

The pictures follow the story of the fall of Troy to the very point where Aeneas’ story in Book 2 [of the Aeneid] will begin; Aeneas himself will paint the rest of these pictures, as it were, when he tells the story of what happened after the Ethiopian and Amazonian allies came to Priam’s aid. Aeneas knows that the pictures of Memnon and Penthesilea presage the final chain of events leading to the sacking of the city; the sum total of the pictures, especially in the situational context of Juno’s temple, should not be consolatory to a Trojan. These are images not set up as memorials of human compassion, but as triumphant records of the victories of Juno’s beloved Greeks over the enemies she so hates. In the first excitement of seeing the early scenes from the war that so changed his life … it is as if Aeneas momentarily forgot the dreadful context of the artwork … The scene is one of increasing horror as Aeneas surveys the paintings in their terrible order, before he finally cries out after seeing the desecration of his friend Hector’s body: tum vero ingentem gemitum dat pectore ab imo (1.485) Then indeed he gave a mighty groan from deep in his breast. The pictures might have been fitting to help rouse Carthaginian morale during the Punic Wars; they celebrate the worst degradation of the Trojans. Aeneas stares fixed and agape at these images as Dido finally enters the temple and interrupts the tour of her art gallery. (Fratantuono 19)

Fratantuono’s more detailed and more faithful reading of the scene allows us to see that in quoting and re-contextualizing Aeneas’ initial emotional reaction to the artwork in Juno’s temple Diderot seems to have effectively blinded us to the narrative sequence of pathos that leaves Aeneas much more troubled, and much less relieved, than we might initially assume.

That readers should be tempted to quote and re-contextualize the line like this has in part to do with the difficulty of translating it in a prosaic, straightforward way. In a literal, word-for-word translation we would read for ‘sunt lacrimae rerum / et mentem mortalia tangunt’: “there are tears of – or for – things (rerum) / and human things (mortalia) touch the mind”.

In translation, rerum and mortalia take on heightened affective qualities, as they are often generalized to stand in for the fate of being human. Thus, Ronald Austin in his 1971 Oxford edition translates: “even here tears fall for men’s lot, and mortality touches the heart” (Austin n.p.), while Allen Mandelbaum renders rerum in English with “passing things”, and mortalia with “things mortal” (Mandelbaum 17).

But beyond pathos there is also a second aspect that contributes to the temptation to quote and re-contextualize this line and in doing so to disturb its temporality, the temporality it has in the sequence of Virgil’s narrative — and this temptation has to do with the complex temporality of Virgil’s narrative itself, with a structure of prolepsis and analepsis that re-enforces the main themes of his epic, fuses together its parts and shackles those parts in turn to the Homeric tradition.

Inasmuch as Aeneas at first interprets the artwork in Juno’s temple as a sign that he will find refuge on these unknown shores he looks toward the future. Inasmuch as he draws hope from a representation of his own past, he looks toward that past. Both past and present are united in this moment.

His interpretation repeats an act of interpretation in which Dido herself engaged when she first arrived at the very same spot with her followers as refugees from the city of Tyre: “Now deep in the heart of Carthage stood a grove, / lavish with shade, where the Tyrians, making landfall, / still shaken by wind and breakers, first unearthed that sign: / Queen Juno had led their way to the fierce stallion’s head / that signaled power in war and ease in life for ages. / Here Dido of Tyre was building Juno a mighty temple, …” (Fagles 63).

For Aeneas, looking at his own representation in the battle scenes from Troy offers an anagnorisis, a literal, pictorial recognition of himself that is part of an emotional crisis: “Aeneas gives a groan, heaving up from his depths, / he sees the plundered armor, the car, the corpse / of his great friend, and Priam reaching out / with helpless hands … / He even sees himself / swept up in the melee, clashing with Greek captains, / sees the troops of the Dawn and swarthy Memnon’s arms.” (Fagles 64).

For Virgil’s Augustan reader, Dido’s interpretation of the stallion’s head as “… power in war and ease in life for ages …” is offered up as a fulfilled prediction, a proleptic description of the power and wealth of the Carthage that was to be Rome’s adversary in its two most desperate, formative wars, the first and second Punic War. Indeed, the Aeneid as a whole is structured proleptically by this conflict, and it has often been faulted for this constraint of imperial flattery, which projects existing history back in time to re-create a founding myth for the Augustan Roman empire, an analepsis that purports to be a prolepsis, a vaticinium ex eventu, a prophecy fulfilled that strains to pretend the outcome could be any different.

It’s now time to interrupt our close reading of this passage and take stock of what we have done.

(1) We have applied techniques of close reading to a sample passage from Virgil’s Aeneid.

(2) We have tried to account for the difference translation makes in our interpretation of this passage.

(3) We have applied technical terms from rhetoric, art and literary criticism (ekphrasis, analepsis, prolepsis, anagnorisis, vaticinium ex eventu).

(4) By taking a closer look at this passage, we have become aware of some important themes and structures of Virgil’s Aeneid that we encounter elsewhere in the poem (e.g., ekphrasis in book 8; vaticinium ex eventu; structures of repetition and imitation that inform the relationship of parts of the Aeneid to each other, and to epic poetry that preceded it).

Where could one go from here?

One could contextualize the passage, either in the context of a reading of Diderot or of reading Virgil, with the ultimate goal of contributing to an interpretation of the work of one of these two authors. One could also connect this sample reading to larger theoretical concerns. One such concern that has informed my own approach to literature is reader-response criticism and hermeneutics, another a conscious application of rhetoric to the study of literature. In order to do so, one would have to take into account more detailed readings of this passage by specialists like the classicist Michael Putnam, who dedicates a chapter to it in his 1998 book Virgil’s Epic Designs: Ekphrasis in the Aeneid. One could also engage in an informed visual analysis (Essay #2!) of art work depicting this passage in Virgil, like the works by Sebastian Brant and Sebastiaen Vrancx featured here.

Works Cited

Diderot, Denis. Oeuvres Complètes. Gen Ed. Herbert Dieckmann, Jean Varloot, Herrmann, 1975, vol. XIV.

Fratantuono, Lee. Madness Unchained. A reading of Virgil’s Aeneid. Lanham, 2007.

Virgilius Maronis, Publius. Aeneidos. Liber Primus. Ed. R.G. Austin, Clarendon Press, 1971.

Virgil. The Aeneid of Virgil. Tr. Allen Mandelbaum. University of California Press, 1982.

Virgil. The Aeneid. Tr. Robert Fagles. Penguin, 2006.

Further Reading

Putnam, Michael C. J. Virgil’s Epic Designs: Ekphrasis in the Aeneid. Yale University Press, 1998.

Oliver Berghof received his PhD in Comparative Literature from UC Irvine in 1995. He taught in the Humanities Core program as a graduate student between 1992 and 1995, and has done so again as a lecturer since 1999. A native of Germany, he specializes in European Literature, Literary Theory and Humanities Computing. In teaching Humanities Core, he particularly enjoys the challenge of teaching students in UCI’s Honors Program.

Oliver Berghof received his PhD in Comparative Literature from UC Irvine in 1995. He taught in the Humanities Core program as a graduate student between 1992 and 1995, and has done so again as a lecturer since 1999. A native of Germany, he specializes in European Literature, Literary Theory and Humanities Computing. In teaching Humanities Core, he particularly enjoys the challenge of teaching students in UCI’s Honors Program.