By Bernardo Bátiz-Lazo (Northumbria University and Universidad Anahuac) and Ignacio González Correa (University of California, Davis)

In our project, we looked at family remittances between the United States and Mexico, the third-largest remittance corridor worldwide by volume, after China and India. By family remittances, we mean cross-border transfers of funds that originate from a sender to a beneficiary. The sender is a migrant worker (documented or undocumented, Mexican-born or offspring with at least one parent born in Mexico), who sends a share of their income—around 20% of their wage, or an average US$370 per month, in two or three installments—across the border. Beneficiaries are family members, typically women—mothers, close relatives, or spouses.

“One fascinating aspect of this market is that approximately 90% of the flows originate and end in cash.”

One fascinating aspect of this market is that approximately 90% of the flows originate and end in cash. We focused on trying to map the industrial organization and technological infrastructure of this market, especially market frictions involving the use of cash, while other colleagues have focused more on individual transactions. We assessed how in Mexico, a country with a large unbanked population and widespread use of cash, the digital economy and financial technology could help to reduce frictions and reduce the average cost of cross-border payments by 3%, which is one of the UN 2030 sustainable development goals.

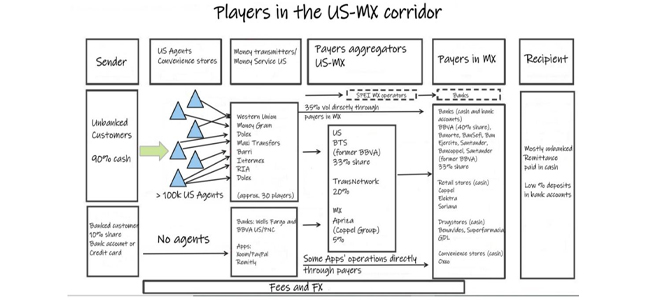

There are several levels to the remittance market, and each has a quite different industrial organization. It is also notable that there is no single intermediary working on either side of the border. Part of the reason for this is that in the United States, licenses to supply retail financial services are issued by individual states. This means a company working across the United States has to develop a large network of retail points to collect money and comply with a diverse set of regulations, which is not impossible but does require significant resources. On top of that, the company would have to comply with Mexican regulations and then develop a retail presence at the granular level, which would require further investments and compliance costs.

At the retail level, there are over 100,000 remittance agents in the United States, while at the same level, there is a plethora of payers in Mexico, from bank branches and ATMs of BBVA Bancomer, Banorte, and Banco Azteca to some 22,000 outlets of retail shops like Oxxo, plus drugs stores and supermarkets like Soriana. There are also others, such as white-goods sellers like Elektra and Coppel, with about 1,000 physical outlets throughout the country.

Another level is the remittance companies. Western Union had 80% of the market in the 1980s, which dropped to about 30% by 1995 and 12% by 2010. In the same period, some 60 remittance companies emerged, though consolidation has left some 30 of these remaining today, and it is likely that consolidation will continue. Every morning, the remittance companies credit their accounts with their estimated volume of business for that day at one of the “aggregators”: agents that intermediate with the banking system, and where the likes of BTS and TransNetwork control some 60% of the volume.

The last layer involves the actual transfer of funds. The US-Mexico remittances bypass the SWIFT system, the international payments switch. Instead, the central banks have created dedicated “pipelines” that some participants can access. At this level, the aggregators with a bank license their account at their corresponding Mexican bank or ask their bank to do so on their behalf. This is the most concentrated part of the industry, as there are about 15 banks that control the cross-border market worldwide.

Then there are the Fintechs, such as Xoom (by Paypal), Remitly, Wise, and Global66, which are newcomers and only have a small portion of the market. They work mainly with middle-class or banked individuals and small- and medium-sized companies.

Alongside proving a snapshot of the infrastructure and industrial organization of the remittance market (see our full report for those figures), some of our notable findings include documenting how, in the Mexico-US corridor, senders have a relatively high degree of bancarization (percentage of the population that has access to and uses retail financial services) but do not want to take on digital payments.

Some of the reasons why they initiate their transfers in cash include an aversion to fiscal and migration surveillance. There is also a very low threshold for failure and a strong tendency to go for “tried and tested” methods. Hence, if the transaction has been traditionally started in cash, they repeat the model. There has been very little update of “innovative” digital channels, even during COVID, when remittance companies opened these to increase convenience. Finally, about 20% of migrants are now women, and a small portion of the overall number (about 6%) are from Indigenous communities that do not speak or read Spanish, so they follow the lead of friends or stewards.

The beneficiaries of remittances are mostly women—mainly elder relatives or spouses of migrants. Mothers tend to be the largest category of recipients, as senders are often single men in their late teens or twenties.

According to the World Bank, there are 304 million women without access to bank accounts in Latin America, which can cause issues for potential beneficiaries. Beneficiaries have also been subject to poor services and high commissions from banks, so they are fearful and skeptical of financial intermediaries. However, there have been some recent successes, such as BBVA in Mexico, which, after several years of investment and hard work, migrated 85% of its 14 million transactions paid in cash in 2015 to paying 85% of its 18 million annual remittances through N2 prepaid cards in 2022.

A major challenge for fintechs is complying with Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations. As noted, in the United States, regulations are primarily at the state level, and a single state authority has the power to audit your entire operation (from all sources and all the way to the final payment, wherever that may be), so keeping accurate records and remaining in compliance is a major concern for remitters and payers. There are significant investments to be made in this area to keep regulators happy and deter money laundering. Fintechs thus have to come up with an innovative business model that satisfies regulators but also other agents, as auditors can focus their inquiry on the whole value chain. Another relevant barrier is that many beneficiaries live in rural areas in Mexico with little mobile phone coverage and little internet access, making it difficult to send money digitally through apps.

Finally, there is an uncomfortable yet indispensable analysis to be made beyond ours. The growth rate of remittance flows is far greater than the growth of migrants or their nominal income. There are thus accusations of an increase in illicit activities. Whether or not this is the case, sound evidence has yet to emerge to quash suspicions.

What have we learned from this? There is a complex infrastructure and industrial organization that makes up this market. There is intense competition at many layers that coexists with strong customer inertia. Participants moan about the cost of regulatory compliance, while outsiders question the integrity of the system. It is only superficially that this market seems ripe for disruption.

This work was conducted as an independent 2022 research project on central bank digital currency and financial inclusion, in collaboration with Maiden Labs, the MIT Digital Currency Initiative, and the Institute for Money, Technology & Financial Inclusion, and funded by the Gates Foundation. You may view the context of this study on the IMTFI blog and details of the new research report release here.