Audrey Alo draws upon over 20 years of experience as a community volunteer, advocate, and educator in her current position as the President of the Pacific Islander Health Partnership (PIHP). Here she works with Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) communities to conduct research, train leaders, collaborate on projects and grants, and provide support for the range of health conditions that disproportionally affect NHPIs. In this interview she discusses PIHP’S work to provide COVID-19 and pandemic support, and intergenerational connections within NHPI communities.

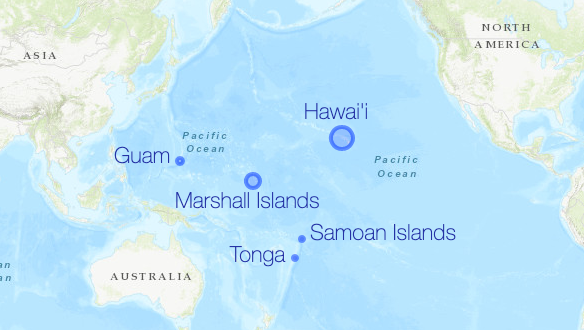

KEYWORDS: work, Pacific Islander, Southern California, community, groups, elders, numbers, Hawai’i, Garden Grove, Island, Marshall Islands, Tonga, Samoa,

Interview Transcript

Pacific Islander Health Partnership has been up and running since 2003. We started at OCAPICA, when OCAPICA was further up on Garden Grove just off of the 22 [freeway], through Mary Ann Foo’s leadership, and be able to bring us together with the Asian American community. We’ve been doing our work now since then.

One of the unique things about the Pacific Islander Health Partnership is that we have, right now we only have, I think, five or six Island groups. So we have Chamorro—so it’s Guam, Tonga, Samoa, Marshall Islands, and Hawai’i. So now we only have five Island groups. And so basically, how it works is that you have, we asked for two representatives from each island group that are selected by their community to come and sit at the table. And so whatever it is that we’re discussing there, it is up for them to disseminate that information back to their groups. And if we’re looking to work on a project, a grant, whatever—then they need to go and get the buy in from their community, and come back to us. And then we can vote, and move forward, and implement, and all that kind of stuff.

[How Has Covid-19 Affected the Community You Serve?]

Lately, I’m working with the Southern California Pacific Islander COVID-19 Response Team, and it’s part of a national effort. So we have people [in] Washington, DC, Washington State, Oregon, Northern California, Southern California, Arkansas, Arizona, and Hawai’i. So we’re trying to figure out how we can help our people get through COVID. We looked at the numbers here in Los Angeles. Although our community is very, very small, we are very, very highly impacted, highly impacted. So I forget what the numbers were the other day—so they can talk about percentages, or they can say that out of 100,000 these many people are affected. But the most impactful numbers for me, are when we say that, out of my community of roughly 20,000 people in Southern California, 1 in 177 people test positive [at time of the interview]. I happen to know a family—one single family, multi generational—where the son, the son-in-law, and the father all tested positive. And so they had to put everybody else in the house out, they had to go stay with other family members. And the father stayed in his bedroom, the son stayed in his bedroom, and the son-in-law ended up, they pitched a tent in the driveway for him to quarantine for two weeks.

Even for some of the elders, it’s being secluded and isolated. They don’t have that person to person contact. So we do the phone trees where we’re calling them and we take turns calling, just so that they know that somebody’s out there thinking of them.

[Final Thoughts About Your Work]

The Western world, they want that alphabet soup behind your name. A lot of what I have between my ears are things that I learned from aunts, uncles, my grandmother, my mother that has no certificate. My certificate is when they nod at me and tell me that I did a good job. So even though I live in a Western world, and even though I’ve acquired the alphabet soup behind my name, the ones that are most important to me are the ones that come from my elders. And so even to talking to people at conferences and stuff like that—they’re so lettered and all of that. So that still means nothing to me. I work with doctors all the time. Doctors just have education in medicine, and they have the expertise of having worked with patients. But I have expertise in other areas. And so, I think with our young people, it’s trying to get them engaged and seeing that they have so much to give.

Interviewers: Taylor Nakatsuka and Nicole Batoy

Related Resources

- This interview was conducted on May 25, 2020 and represents a moment in time; but the work of Audrey and the Pacific Islander Health Partnership remains ongoing. Please visit their website to learn more about their initiatives, programming, and progress. Pacific Islander Health Partnership. https://www.pacifichealthpartners.org/

- Southern California Pacific Islander COVID-19 Response Team. https://pi-copce.org/covid19response/

- Data regarding COVID-19 infection rates among NHPI in California. “CA Counties Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander COVID-19 Dashboard.” UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, January 16, 2021. https://public.tableau.com/profile/richard.chang7038#!/vizhome/CA_County_Dashboard/Story1