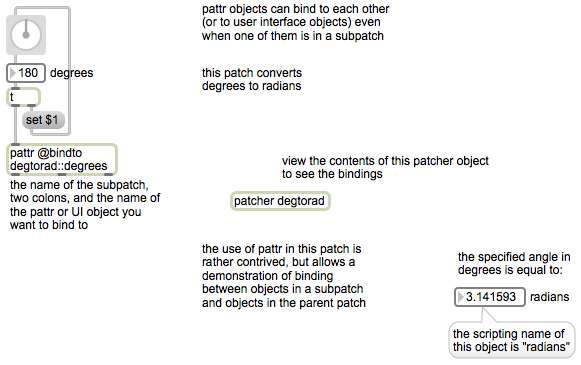

A pattr object can be remotely bound to another pattr or to a UI object, using the bindto attribute, even if one of them resides in a subpatch. To indicate an object in a subpatch, the syntax for pattr‘s bindto attribute is to use the subpatch name, followed by two colons — :: — followed by the name of the object to which you want to bind. Use of that syntax is shown in the pattr in the main patch. Notice that to do this with a patcher object, the patcher needs to have a name typed in as an argument. And of course the object to which you intend to bind needs to have a name, too. If you look inside the patcher degtorad subpatch, you’ll see a pattr object with a typed-in name degrees. The pattr in the main patch can bind to it by using the patcher object’s name and the name of the pattr object inside the subpatch.

To communicate in the opposite direction, from a pattr in a subpatch to some object in the main patch, you just refer to the patch one level above using the name “parent”. In our subpatch, we have a pattr that is bound to the number box named “radians” in the parent patch. (Although it’s not demonstrated here, you could even bind objects through multiple levels of subpatches, using multiple :: symbols, as in @bindto parent::parent::radians.)

You may wonder, “Why couldn’t we just put an inlet and an outlet in the patcher subpatch, and communicate with it via patch cords?” And you’d be quite right. In this simple example, that would be easier. (But it wouldn’t have given us the pretext to discuss the :: syntax.) In more complex situations, you’ll see how the ability to bind a pattr to objects on other hierarchical levels can be useful.

Notice how, in this example, the pattr objects in the subpatch have typed-in names, but the one in the main patch does not. We didn’t bother to give that pattr a name because no other object needs to bind to it. (It takes care of binding to the degtorad::degrees object all by itself.) As far as Max is concerned, though, all pattr objects have a name. If you don’t type one in, Max internally assigns it a quasi-random name.