Interactive Space to the Max

June 6th, 2013, 6-8 pm

ACT 2200 (Game Lab)

For this showcase exhibition, the students in S.A. 106A Programming for Artists created interactive and participatory projects ranging from meta-self-portraits to absurdist games. The artists included were Kenneth Fernandez, Aki Imai, Brian Lac, Patty Lin, Melody Liu, Patrick Magno, Alex Morishita, Nhue Nguyen, Alexa Schlackman, Sona Shah, Justine Tung, Rebecca Viehmann, and Jessica Yean. Below are the artists’ own descriptions of their projects.

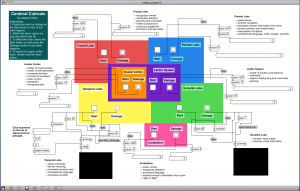

Jessica Yean’s Cerebral Cubicles is an interactive piece that guides the user to learn about the human brain by directly “probing” its different color-coded regions. Guided by instructions provided, users discover that each brain region has a certain personality shaped by its specific roles in brain activity. Unexpected results occur when the user experiments with the “brain damage” feature. The overall aesthetic of the piece is inspired by scientific diagrams and information design (typified by labeling and bullet points), as well as by the current metaphor of the brain as a complex supercomputer, embodied here by making the components of the MaxMSP program itself visible.

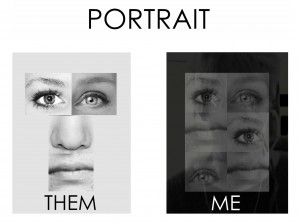

Patty Lin’s project is simply entitled Portrait. Lin has always been intrigued by the subject of beauty, whether that physical or internal. We are bounded by many things and our choices are often limited. We can’t choose what race we are born as or which family we are born into. We certainly cannot chose our appearance, at least not before birth. We can change how we look temporarily or permanently with the help of artificial procedures. Lin’s project simulates such artifice by allowing the participant to select a generated face and “try it on.” However, in her project the faces don’t match and none of the features come from the same face. The face is also scrambled, so that the participant has no control over whether the eye goes where the chin should be or the nose on the mouth. This underlines the fact that though we hope to control how we look through prosthetic alterations, there is only so much we can do on the outside. In order to change ourselves, we must do it from the inside.

Patty Lin’s project is simply entitled Portrait. Lin has always been intrigued by the subject of beauty, whether that physical or internal. We are bounded by many things and our choices are often limited. We can’t choose what race we are born as or which family we are born into. We certainly cannot chose our appearance, at least not before birth. We can change how we look temporarily or permanently with the help of artificial procedures. Lin’s project simulates such artifice by allowing the participant to select a generated face and “try it on.” However, in her project the faces don’t match and none of the features come from the same face. The face is also scrambled, so that the participant has no control over whether the eye goes where the chin should be or the nose on the mouth. This underlines the fact that though we hope to control how we look through prosthetic alterations, there is only so much we can do on the outside. In order to change ourselves, we must do it from the inside.

Nhue Nguyen’s The Visitor functions as an ad-hoc documentation of every user that interacts with the piece. The audience is taken on an adventure to another land and progresses through it by providing data about themselves in various ways: by answering questions, by experimenting with a webcam feature, by drawing in a sketchbook. In the end, a collection of personal profiles is compiled, archiving the footprints of the visitors. The project is slightly customized for the exhibition “Interactive Space to the Max,” but it can be installed elsewhere as well.

Paying homage to illustrative searching games like “I Spy…” and “Where’s Waldo?”, Magno’s Find Happiness prompts viewers to “find happiness” by clicking on a particular sequence of objects until the program tells them they have found it. The vagueness of these instructions along with the ambiguity of the environment make the task purposefully confusing and difficult. Each viewer may interpret the the various visual objects differently—some may think the colors evoke happiness, while others may associate the imagery with something like rock candy associated with childhood happiness. It becomes a game investigating what happiness looks like, and how frustrating and intangible a concept it is. The imagery in this piece is abstracted from blockbuster movies, which are products of a media entertainment complex that feeds us generic ideas of happiness.

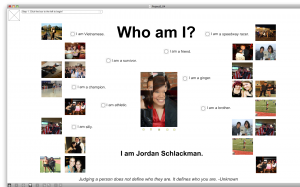

Alexa Schlackman’s Who Am I? is an interactive media project based on the concept of judging and labeling others solely by visual cues. In the piece the user is given a list of various activities, starting off with a simple matrix puzzle of a person’s portrait. Following this step, the user is instructed to randomly click through the text in order to match the written aspect of the piece with the completed image. If the user is able to correctly match all nine descriptions of the person to the image, the user will be rewarded with the name of the character. However, since most users will be guessing the answers based on snap judgments rather than prior knowledge, the final step is to answer the question “Who am I?” by labeling—or as some say, naming—the individual’s profile that has been created. While the interface for the project may seem simple, the underlying message is more complex. Included at the bottom of the artwork is a set of randomized quotes warning the viewers to be careful about judging others; for example: “Judging a person does not define who they are. It defines who you are.” Yet the piece also explores our daily dependence on labeling. Many times in life one is referred to by a specific category, like “the girl who is a figure skater.” In instances like these, where there is some truth to the label, other people will tend to remember the person only for that single talent as a skater and forget to notice all the other attributes and characteristics. Finally, by asking the viewer to put a name to the face that has been uniquely envisioned and described, the artist hopes to bring to the forefront the idea of a name. Is it simply another label, or does it somehow embody the looks, personality, and overall talents that one has?

Rebecca Viehmann’s work History explores the relationship between textbook definitions and popular culture of what defines our society. Advertisements flash across the decades, of which the user has no control. Text of important dates in history can be filtered through with a click of each image. It is up to us as individuals to seek out information, but if we choose to learn nothing, propagandic images still wash over us in alarming numbers. The juxtaposition asks the user to decipher what they find important about our past— horrific events, fashion, television, civil rights, etc. Audio can be played, one set of songs tied to the older decades, the other tied to what our current generation of 20-somethings can remember. Songs can be played over one another, volumes adjusted, distorted, and can produce a haunting cacophony of sound that battles each other for attention. “History” probes at the struggle between forces of what we define as our past, but does not come to a concrete answer.

Alex Morishita’s Road Cycling Grand Prix is an interactive bike racing game. The large center screen is the main level of the game, while the three videos below are the players’ control options and “map awareness” area. During the game, players must complete certain abilities to gain points to increase their skill level at racing. Controls such as “space warp” testify to the fact that this is a surreal bike-race game like none other.

Sona Shah’s project, The News Room, is based on the distractions of the media, specifically reality TV shows that take away from more important information in our lives. People tend to know more about the people on reality TV or in the media than who their own governor or secretary of state is. It is vital that people understand the importance of knowing what is going on locally, nationally, and worldwide; the events that emerge and people that rule, will affect us now and in the future.